Isle of Man TT: The serenity of ‘horizontal skydiving’

It is the start of this year’s Isle of Man TT, where speed junkies race along public roads. Tom Peck gave it a go and found that something strange happened to his fear

The jolt was almost undetectable, as if a magician had whipped the Tarmac out from beneath us. Then the asphalt filled my eyeballs, and then the sky. Then the road. Sky. Road. Sky. Road. Turning like a flickbook. The rest, I don’t recall.

They say of the TT riders what they say of soldiers. “He died doing what he loved.” And in a sense, that’s true of me too. I loved being a journalist. But it’s the World Cup next week, and I would have loved to have been one for just a little bit longer.

Alright, so none of the above actually happened, but when I accepted the offer of a pillion ride round the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy course, on the back of the superbike of one of its many unhinged former champions, some hilarious colleagues suggested it might be wise to file my own obituary in advance.

So having spent a full fortnight consuming the near comic abundance of jaw dropping TT wipeouts on Youtube, not least the 2003, 160 mile an hour spectacular from Richard ‘Milky’ Quayle, the chap who, one spleenless decade on, would be driving me around, this was how I pictured my end.

The reality was something very different - an unimaginable, unforgettable wonder. But more on that later.

In the hundred and seven years since the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy was first up for grabs, somewhere in the region of 250 racers have been killed on the quaint village streets, the country lanes and the high mountain roads . The exact number, beguilingly is not known. And this figure doesn’t include the ‘Mad Sunday’ racers, wildly enthusiastic amateurs who tear round on the festival’s first sunday, which is today.

The temptation, from the outside, to focus on this extraordinary statistic is overwhelming, but it has never, and will never deter those for whom the TT means everything, and they are many.

The island’s population has swelled from 80,000 to 130,000 or more. Many hotel beds for next year are already booked. The local rugby pitches are covered in tents. Some come by airplane, but most have come via the ferry from Liverpool and have brought their bikes with them.

“There is nothing in the world like the Isle of Man TT,” says Michael Dunlop, who won the first race yesterday by a huge margin. “It is the Monaco of Motor Cycle Racing. Monaco hasn’t changed since the 1950s, and nor has this.”

He is one of a whole host of Dunlop fathers, sons, uncles and brothers who have near dominated this track for decades at a time. “King” Joey has still won the most TT races: 26. The most recent came in 2000, at the age of 48. He died the next month, crashing in a race in Estonia.

It’s not hard to imagine the Isle of Man as being unchanged from the 1950s. The local radio has that unmistakeable local radio twang, as in tones of purest Partridge the breezily imparted chatter rhapsodises on a constant theme.

“Just back from the hospital. Laurent has 2 broken femurs which were operated on last night, 1 pinned and 1 screwed. He is a bit groggy still but ok in himself. When he came round, he asked, “Will I still be able to race next week?” Ha ha, we think not Laurent.

““Anyway, the funeral of Simon Andrews will take place at Worcester Cathedral, on Tuesday 17th June. All welcome, with donations going to the air ambulance.”

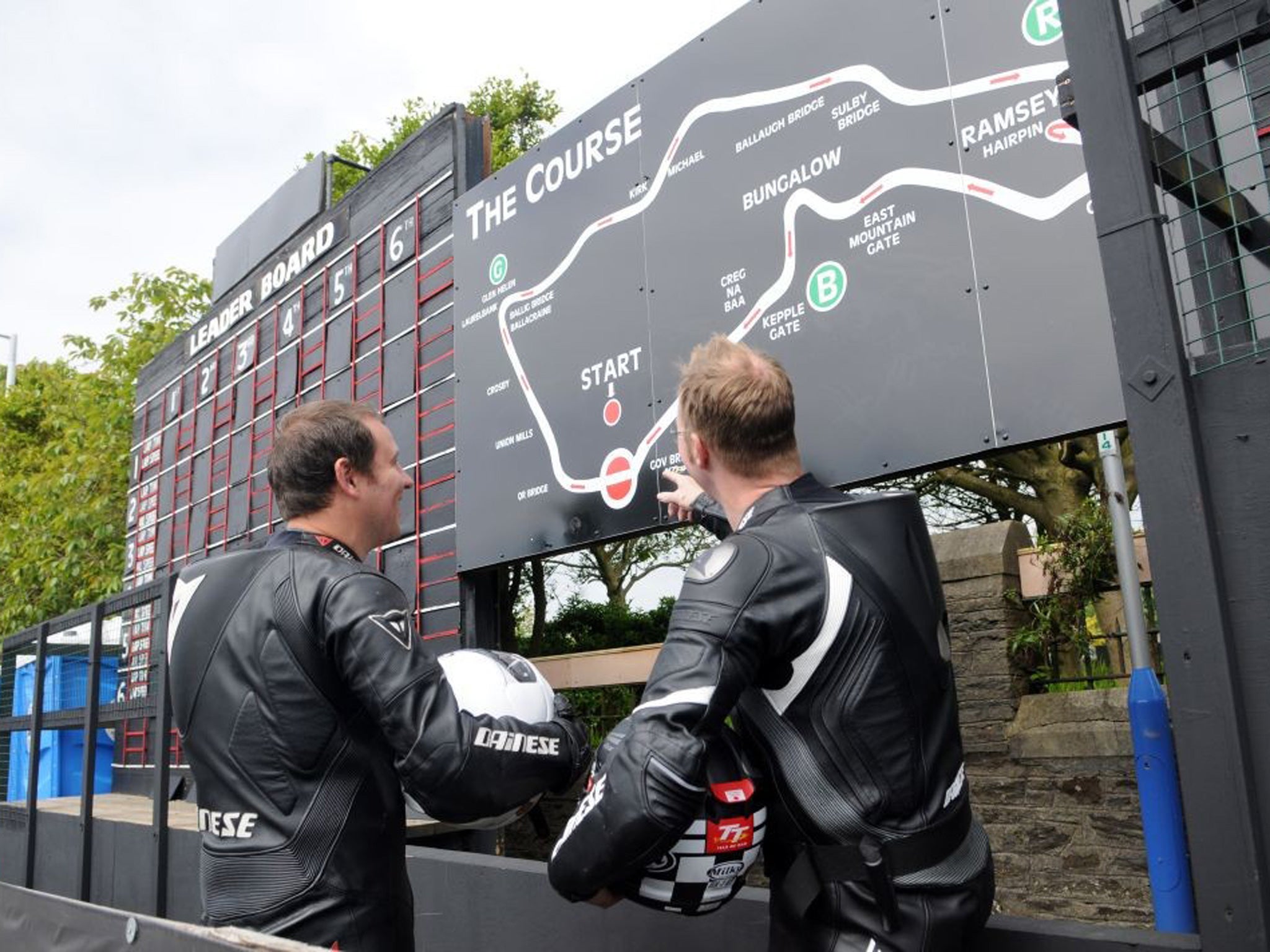

The course is 37 miles long, races run over six laps. Long stretches are taken at over 200 miles an hour.

To win, the riders will need to maintain an average speed of more than 130mph for almost an hour and three quarters, knowing all the time that even the tiniest mistake will have consequences far beyond the race.

And it needn’t be a mistake. A rush of blood to the head from a kamikaze rabbit will work just as well, as will many other factors entirely beyond the rider’s control, a reality I’m acutely aware of as i insert my legs into fifteen hundred quids worth of Italian leather, pull a helmet over my head and take my seat high on the back of Milky’s Yamaha R600.

Milky, himself a Manxman, won a TT race in 2002 the year before his very famous crash. In hospital, unable to speak, he wrote a note to his pregnant wife that said, “no more races.” He has kept his promise. Now he introduces the rookie riders to the course.

“Some people want to be an astronaut, or a professional footballer, but they’ll never achieve it. I wanted to be a TT champion, and I am. If I died tomorrow, I’d be happy.” If he died tomorrow, I’d be sad, but today is my my more immediate concern.

Very short moped taxi rides in south east Asia notwithstanding, this is my first time on a motorbike, and very regular readers of The Independent might know I only learnt to ride a push bike two years ago, but that’s another story.

The engine revs, the pit lane clears and we’re off. It’s not a race day, so the opening sections of the course are still open for normal traffic, and the speed limits are in place.

In the towns and villages we sit behind traffic - almost all of it motorbikes - and zipping along past little pebble dashed houses with pretty front gardens out in bloom.

The next day, they - and I - will be drinking beer in the sunshine, leaning our heads over the low stone walls as the bikes come screaming past at 180 miles an hour, one after the other, after the other, after the other. When you first hear them they’re still hundreds of yards away, then a microsecond later a bright shape appears with the roar of jet engine then disappears, leaving the windows shaking.

A few years ago, Valentino Rossi watched the races from one of these front gardens and as the first bike went past, three feet or so from his face, he visibly blanched and the only English words he could find were, “Blady ‘ell, a blady ‘ell, a blady ‘ell!” When asked if he fancied a go, he held his arms between his legs like he was carrying watermelons and said: “No. These guys, they have a bigga balls.”

“People say oh you’re crazy, you’re disrespectful to the gift of your life,” says Milky. “I disagree. If you live your life on the edge you value life. People who get up in the morning, walk to the station, get on the train, sit in the office, get the train home, go to bed, get up and do it again - they’re the ones who are disrespectful to their lives. What we do is the ultimate. The ultimate.”

We pass the Ginger Hall Hotel, a well known pub on the circuit whose inside is covered with TT memorabilia, and we’re overtaken by a man with crutches strapped to the side of his bike. He can’t walk, but he can ride.

The Ramsey hairpin marks the entrance to the mountain stage, where the road is one way all week, race conditions. Without saying a word, Milky turns the throttle, the engine whines, we’re up to 135 miles an hour, and the world is transformed. The rolling pasture, the sheep, the hedgerows, have been smeared like wet paint across the horizon, and suddenly something curious has happened. The fear is gone, in its place something a bit like serenity, and it’s clear in an instant that it is this, not the fear of death, on which these leather clad junkies have become dependent. This feeling of horizontal skydiving - adrenalin; speed.

“If we just did it for the adrenalin, for the fear of death, we’d just go and play chicken with the traffic. It’s not about that,” he says when we’ve turned past yet another packed beer garden and turned back into town.

At around 50mph, we pass a “Children. SLOW” sign outside a primary school and the driver in me instinctively reaches for the brakes. All week the riders will come past here at 180 miles an hour or more.

Extraordinary individuals perform extraordinary feats all the time. But it’s rare they do it in in such an ordinary albeit beautiful place - on their way past the post office, the local shops and the village green.

Back in the pits, I disembark and Milky pats the bike. Normality is a disappointment by comparison. That emptyness, of the kind that comes after a big win at the bookies. The money’s still in your pocket, but the buzz is gone.

“Eight grand that, straight out the shop, and it’ll outperform a Porsche or an Audi, anything like that. It’s a working man’s Ferrari.”

He’s right. The ubiquitous leathers can’t help but lend their wearers that 50’s Americana cool. But the people here aren’t cool. They’re not F1 drivers. They’re not footballers. They’re ordinary in their extraordinariness. They just love that indescribable thing called speed.

Bennetts, the UK's No.1 bike insurance specialist, is an official sponsor of the Isle of Man TT Races -www.bennetts.co.uk / www.iomtt.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments