The story of Bill Tilden and the city torn over whether to forgive great or not

FEATURE: Calls for former Grand Slam champion to be recognised in hometown have caused a debate in Philadelphia

Surely, it's not asking much. Just a local historical marker, a plaque roughly one-foot square, to commemorate arguably Philadelphia’s greatest athlete ever – among the foremost players of his sport, who helped change its history for ever.

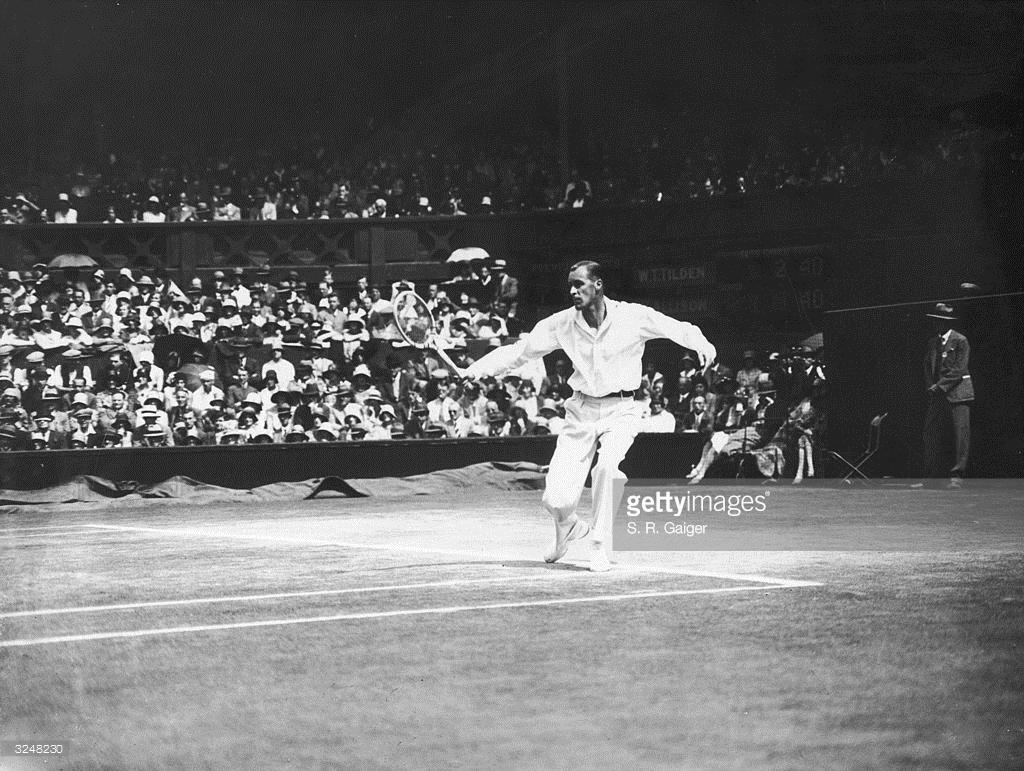

During the 1920s Bill Tilden dominated tennis. He won 10 major titles, the US National Championships (as the US Open was then known) seven times, and Wimbledon three times (which would surely have been more had he not skipped the tournament for five straight years while at his peak).

He went through the entire 1924 season without losing a single match.

At his peak ‘Big Bill’ – 6ft 2in tall, with a telescopic reach and every shot in the book – was a pillar of American sport’s so-called “Golden Age,” up there with Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey and the golfing prodigy Bobby Jones.

Like Ruth and Dempsey, Tilden was a larger-than-life figure, who seized the public imagination.

In 1931 he turned professional. With him aboard, the fledgling pro tour became a viable long term proposition, a key step towards big-time tennis as it is today, no longer “shamateur” but open to all, where the best players earn the money their skills deserve.

Yet no plaque has materialised. Instead, in the words of Allen Hornblum, researcher, author, and one of the leaders of the campaign for a marker, Tilden became “the most forgotten great athlete in American history.”

The reason? Two convictions and jail terms he served in California in the final decade of his life for sexually molesting teenage boys.

Sporting glory was submerged by inglorious, tragic scandal.

A man born into a well-off and socially prominent family, who had consorted with kings, presidents and Hollywood movie stars, died alone in 1953 aged 60 in a Los Angeles boarding house, with a net worth of just over $88.

In the US at least, the disgraced Tilden was airbrushed out of history – and nowhere more so than in his native city.

Tilden was a child of Germantown in north west Philadelphia, once a green and wealthy suburb of imposing mansions, but which has declined along with Philadelphia itself, America’s third city after New York and Chicago less than a century ago.

His father was a wool merchant, well connected in Philadelphia society. For years his home was one of those mansions – now converted into eight apartments – barely 100 yards from the Germantown Cricket Club where he honed his tennis skills.

Do not be misled by the name. Once the place was indeed a home of cricket, hugely popular in 19th century Philadelphia.

In the long central hall of the clubhouse hangs a photo of a match in 1891 between Lord Hawke’s XI Gentlemen of England and The Gentlemen of Philadelphia (which the Yanks won.)

The stunning main building, looking out over acres of immaculately tended lawn is testament to a vanished era.

Separating it from the gritty, predominantly black neighbourhood which now surrounds it, is a fence of wrought iron and weathered brick pillars that would grace an English country estate.

But by the turn of the 20th century, cricket’s charms were fading. Philadelphia turned into a baseball town, while at GCC the emphasis switched to tennis – and in the process became one of the sport’s hallowed places.

In summer that expanse of emerald lawn is filled by 24 tennis courts, standing on the spot where three US National Championships and five Davis Cup finals were held.

And traditional standards hold: none of the technicolour garb to be seen at most tournaments these days. GCC has long since admitted blacks and women as members. On those 24 courts however, the dress code remains all-white, enforced with Wimbledonian rigour.

Bill Tilden is far from all of the club’s history, but he’s an integral part of it. There he perfected his thunderous serve, known as “The Cannonball.” There he won three of his national titles, from 1921 to 1923.

From there, and despite many run-ins with the game’s starchy ruling body, the USLTA, he worked to turn a game for the privileged few into a mass sport. And he wasn’t only a tennis player.

He wrote 30 books, many of them indifferent. But he also produced manuals on tennis that stand up to this day. He loved music, read voraciously and – albeit with scant success – wrote and bankrolled Broadway plays.

As a boy he might have been shy, but his on-court style was flamboyant and arrogant. “To opponents it was a contest,” wrote the sportswriter-turned-novelist Paul Gallico. “With Tilden, it was an expression of his own tremendous and overwhelming ego, coupled with feminine vanity.”

During his playing career however there was little talk of homosexuality. That only became an issue later, as his tennis powers began to wane.

The nadir was the two incidents in Los Angeles, in 1946 and 1949 when Tilden was already well into his 50s. They didn’t stop him securing top spot by a huge margin in a 1950 Associated Press poll of the best tennis players of the first half of the 20th century.

Nonetheless it was a prudish and buttoned-up age and the country was shocked – not least because the affair revealed top sportsmen too could be gay.

Disgrace engulfed him. Although he has kept his place in the Tennis Hall of Fame, GCC stripped him of membership, and the University of Pennsylvania, his alma mater, removed Tilden’s name from its register of graduates.

By 1955 Vladimir Nabokov, in his most famous novel, was using Tilden as model for a clapped-out former tennis champion with “a harem of ball boys.”

Humbert Humbert takes him on as Lolita’s coach, knowing he won’t make a pass at her because he is gay. Nabokov’s character is called Ned Litam – ‘Ma Tilden’ spelt backwards.

Only recently has the tide started to turn. The Tudor-style mansion on McKean Avenue, a stone’s throw from the club, still bears no marker. But a named portrait of Tilden now hangs in the club’s hall, along with three smaller ones of the great man in action. And the club seems no longer to object to a plaque outside.

“We’re not seeking a Tilden Avenue, or to put a Tilden statue on top of William Penn’s column [an emblem of downtown Philadelphia],” says Hornblum, whose new biography of Tilden, American Colossus, comes out next year. “we just want a plaque for a great athlete, who made a modern sport.”

In the larger tennis world too the feeling is increasingly that a little forgiveness is in order. Last year the group applied for a marker to the state commission in charge of such matters. It had the backing of two of the city’s crustiest sports institutions, the Philadelphia Cricket Club and the Merion Club (where Justin Rose won the US Open golf championship three years ago), as well as various tennis luminaries.

Among them was Vic Seixas, Wimbledon champion in 1953 and at 92 the oldest living Grand Slam title winner. “Its time to let bygones be bygones, and give him credit for the things he did, rather than focus exclusively on the things he shouldn't have done,” Seixas tells me. But to no avail.

The five-person panel rejected the application by four votes to one, recognising that Tilden’s “accomplishments in tennis are unquestioned,” but stating that his criminal convictions ruled him out.

That however doesn’t tell the whole story. All other things being equal, Tilden might well have had his plaque and a measure of rehabilitation, after the sordid denouement to his life.

But things have not been equal. Since the Catholic priest scandal erupted over a decade ago, child molestation has rarely been out of the headlines in America – and nowhere more so than Pennsylvania, after the Penn State scandal that saw Jerry Sandusky, assistant coach of the college football team, jailed for 30 years for sexually abusing boys over decades.

Penn State also removed a statue of its legendary head coach Joe Paterno, who had turned a blind eye to Sandusky’s transgressions. Worse still for the timing of the initiative, the whole affair is being raked over as Sandusky is appealing his 2012 conviction and seeking a new trial.

Hornblum and his fellow activists though are undeterred. “We’re going to re-apply later this year, and this time we’ll have even more names.”

As for US men’s tennis, without a Slam title since 2003, and not a single representative in the world’s top 15, what wouldn’t it give for a Bill Tilden now?

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies