Virtual reality can be used to treat severe paranoia, says groundbreaking study

Many participants in the study said their paranoia had disappeared after their VR therapy sessions

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Oxford University researchers have found that virtual reality (VR) can be hugely effective in treating people suffering from severe paranoia.

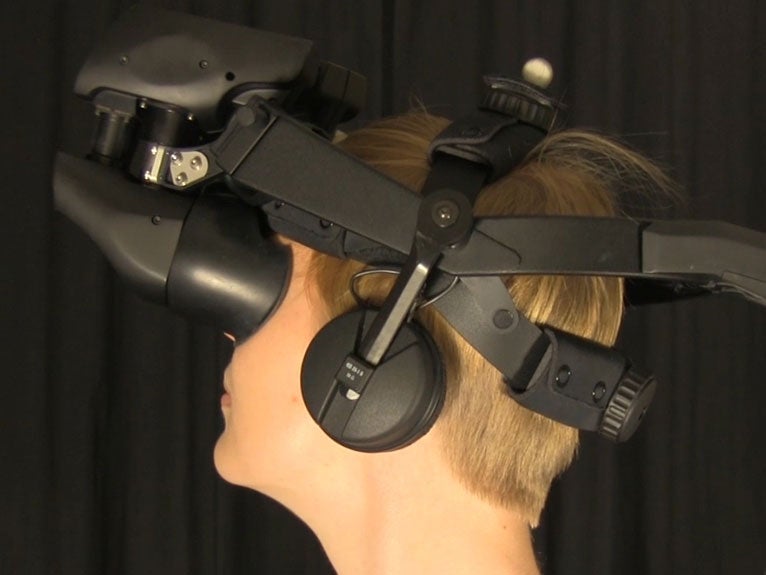

Using top-of-the-range VR headsets, which can track users' movements and immerse them in a simulated world, the Oxford team virtually placed paranoia sufferers in environments they found stressful, like crowded trains or cramped lifts.

By experiencing these places in a controlled setting, the patients were able to practice how to deal with them. By the end of the groundbreaking tests, many of the patients reported a marked decrease in their paranoia.

Around one to two per cent of the population suffers from severe paranoia, usually as a central feature of mental health disorders like schizophrenia.

Sufferers may incorrectly believe that others are deliberately trying to attack, mock or upset them, and the feeling can be so profound in some patients that they are unable to leave the house.

Defensive behaviours, such as avoiding eye contact or limiting social interactions appear to provide temporary relief, but only exacerbate the problem.

In the tests, the participants donned a VR headset and entered a virtual Tube train, which became more and more crowded in each session.

One group of participants were encouraged to use their normal defence mechanisms, but were told that the situation would become more tolerable as they got used to it.

Others were told to drop all of their usual behaviours, and were instructed to approach and look at the human-like avatars inside the train, making eye contact or standing toe-to-toe with them.

This second group experienced the biggest improvements - over 50 per cent of them said they no longer had severe paranoia at the end of the testing day.

Even in the first group, things got better - 20 per cent reported their paranoia had gone after the VR experience.

Professor Daniel Freeman, from Oxford's Department of Psychiatry, said in a statement: "Paranoia all too often leads to isolation, unhappiness and profound distress. But the exceptionally positive immediate results for the patients in this study showed a new route forward in treatment."

The treatment isn't easy for patients, since dropping long-held defences takes time and courage. However, he said: "As they relearned that being around other people was safe we saw their paranoia begin to melt away. They were then able to go into real social situations and cope far better."

"This has the potential to be transformative."

VR has been used in similar ways to treat veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Skip Rizzo, a University of Southern California psychologist and leading VR therapy researcher, has been able to help sufferers by getting them to virtually relive their traumatic battlefield experiences in a safe environment, where they can better process their painful memories and emotions.

Further research will be needed to see if the benefits the Oxford participants experienced lasted beyond the testing day. The therapy should also become more accessible as VR technology lowers in price.

Dr Katherine Adcock, from the Medical Research Council, which funded the study, explained: "There is a lot of work to be done in testing the approach in treating delusions but this study shows a new way forward."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments