New Brunswick: It’s wild and wonderful in this corner of Canada

Despite being just over the border from New England, this Atlantic province remains largely off the tourist map, as Mike Unwin and his family soon discovered

Pfff. The short, breathy report – like the hydraulic hiss of a London bus – betrayed the first porpoise breaking the surface just beneath my raised paddle. More blowhole exhalations followed. They came in volleys as our escorts surfaced together, triangular dorsal fins emerging in gentle, rolling sequence. “Look Dad,” exclaimed my daughter, as one glided beneath our kayak to check us out. “You can see its eye.”

It was mid morning off Deer Island, one islet amid the forested archipelago that litters the map of south-western New Brunswick, Atlantic Canada. Our backdrop was as serene as a Japanese painting: wraiths of mist rising from the glassy water; spindly spruces crowning sculpted rock promontories. Sound carried so clearly that the whine of a powerboat across the bay seemed a brutal violation.

“You never know what you might meet out here,” said Seascape Kayak Tours owner Bruce Smith, as we unpacked lunch on a timber-strewn pebble beach, kayaks hauled up beside us.

“Saw a leatherback turtle once,” he added, tearing chunks from his home-baked loaf and portioning out slabs of salmon. Bruce is all you’d hope for in a Canadian kayaking guide: ragged beard, dry humour, eyes on the horizon. A bald eagle circled overhead as we listened to his stories.

New Brunswick is one of the four provinces that make up Atlantic Canada, along with Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. It also lies directly over the border from the US, its forests an unbroken extension of New England’s.

With the ocean ever-present on our two-week tour, boats had become a theme. Bruce’s dinky two-person kayak was the third different craft in which we’d taken to the water. The first was in Kouchibouguac National Park, back in the north-east. For 3,000 years the Mi’kmaq people fished and foraged for shellfish in these shallow waters and the big “voyageur” canoe, with its team of paddlers, was central to their way of life, allowing them to power right across to Newfoundland. Our party was less ambitious, paddling no further than a sandbar that shielded us from the open ocean. Grey seals bobbed up to watch us pass.

Arrowheads and other artefacts at the park’s visitor centre revealed that the Mi’kmaq also hunted the forests. Our schedule allowed us no time to bag a moose, but returning to our car after a brief tramp in the woods we found a gleaming pile of droppings beside the trail. It looked suspiciously like a bear’s ... But does a bear? In the woods?

My question was answered that evening in a forest clearing just outside the settlement of Acadieville. From a raised wooden observation platform, we watched black bears shamble out of the trees to guzzle peanuts scattered by local bear whisperer Richard Goguen.

“These are wild animals,” whispered Richard. “I wouldn’t want you folks down there right now.” He explained how his relationship with bears started 18 years ago with an orphaned cub and that this protégé had since raised cubs of her own that now return for handouts. This tourist sideline supports his effort to protect the bears from local hunters.

Next day, we drove east along the Route d’Acadie to the fishing port of Shediac. “Acadie” (Arcadia, in English) is the francophone region of Atlantic Canada.

Arcadian flags fluttering from every gas station and garage sale spoke of a proud local heritage. A truck-sized model lobster at the entrance to town also revealed a crucial plank of the local culture. Arcadians once harvested lobsters in their gazillions and “lobster shacks” housed teams of girls who worked their fingers raw under the stern gaze of nuns. The pink flesh was canned: lobster, a century ago, was strictly lower-class fare.

We learned more while chugging out of Shediac harbour aboard the Ambassador, a lobster boat converted for tourist cruises and the second vessel of our trip. Our guide explained everything, from the crustacean’s biology to the industry it spawned, plus how to capture, cook and – of course – eat one. Seated on the lower deck, each with a lobster in hand, we followed his instructions to split and twist our way through the formidable armour and reach the soft flesh inside. It was messy, hilarious and, ultimately, delicious. “I’ve got lobster cramp,” groaned my daughter, flexing aching fingers.

From the Arcadian coast, our route dog-legged south to the Bay of Fundy. This huge inlet, which separates New Brunswick from Nova Scotia, generates the greatest tidal range in the world, up to 15 metres. The phenomenon is best appreciated at Hopewell Rocks, where the cliff has eroded into a clutch of Easter Island-style rock stacks. “Imagine 160 billion gallons of water coming into this bay at high tide,” urged our guide, Kevin Snair, as we peered down on to the beach, now exposed at low tide. “Wait, I’ll show you.” He flipped open an iPad to run a time-lapse video of the sea drowning the sands below us and racing up the rock stacks like a biblical flood.

At the foot of the cliffs, Kevin also showed us the micro-life of the low-tide mudflats, including the mud shrimps that fuel the thousands of migratory shorebirds which pass south every autumn.

Next stop was Fundy National Park, where we turned our back on the ocean for two days to explore the forest trails. While no big beasts materialised, their signs were everywhere: mounds of moose droppings; the gnawed tree stumps of industrious beavers. Meanwhile, my daughter picked out the forest’s ground-level secrets, from fluorescent fungi on crumbling logs to the sticky, pin-cushion heads of sundew plants. The forest was so silent that any unexpected noise – the yodelling of loons from an unseen lake; the sudden roar of the Laverty Falls as we rounded a bend – stopped us in our tracks.

Our southbound journey beside the Bay of Fundy ended at the picturesque harbour town of St Andrews – from where we made our kayaking trip to Deer Island. Downtime saw us strolling along the waterfront and marvelling at the picture-book wooden houses overlooking the bay. And on one indulgent evening we drove out to the Rossmount Hotel, in whose grand colonial dining room we sampled a menu that is celebrated up and down North America’s eastern seaboard. (You won’t beat the fish soup, poached halibut and blueberry chocolate mousse.)

St Andrews is firmly anglophone New Brunswick; the British expelled the Arcadians from this coast in 1755. Best known among those who made the area their playground was President Franklin D Roosevelt, who kept a holiday home on nearby Campobello Island. A small passenger ferry from St Andrew’s Wharf – our fourth boat – took us out to this forested retreat, now connected to Maine in the US, by the FDR Bridge. The Roosevelts first came as tourists in the 1880s. We filed through the rooms – where the polio-stricken president had once hidden from the public eye – peeking at children’s toys and family photos.

Boat number five was the big passenger ferry that carried us and our hire car to Grand Manan. This island sits in the mouth of the Bay of Fundy and marks the southernmost point of New Brunswick. Our base was the charming Marathon Inn, all roses and rickety verandas. For three days we explored the island, walking the cliff paths, dropping into a folk festival and nibbling the dulse – a local seaweed snack – that was laid out to dry in sunny clearings.

For the wildlife enthusiast, though, Grand Manan means whales. Thus our sixth and final holiday vessel was the 18-metre motor-sailing yacht, the Elsie Menota, in which we set out to find them. As a combination of engine and wind power swept us seaward, Alan MacDonald of Whales-n-Sails Adventures explained how plankton blooms draw the great Leviathans into the Bay of Fundy every summer.

Within an hour, the first spouts were breaking the horizon. Surely no firework display or circus stunt can generate more excitement – more “oohs” and “aahs” – than a boatful of people watching whales.

We saw fin whales first: long and sleek, spouting high then slipping below the surface without any fuss. Then the humpbacks took over, slapping huge pectoral fins and rearing knobbly heads to “spyhop”, before saluting with tail flukes in a perfectly synchronised dive.

On a calm summer’s day, with the sunlight dancing on the water, the call of the open ocean seemed irresistible. And home lay just across this pond. No doubt the Mi’kmaq would have kept going – got their heads down and paddled hard. For us, though, that seventh vessel would have to be a plane.

Getting there

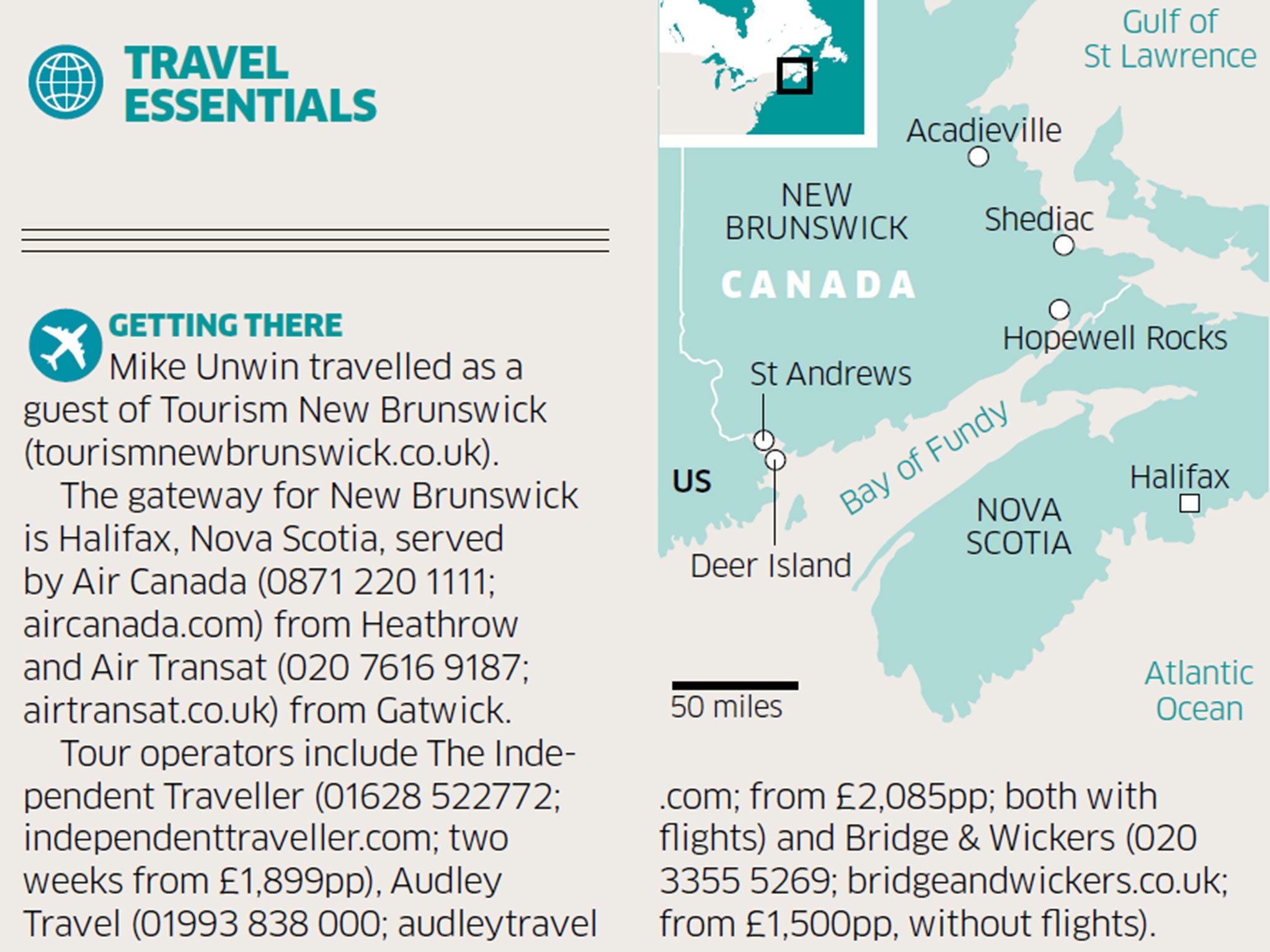

Mike Unwin travelled as a guest of Tourism New Brunswick (tourismnewbrunswick.co.uk).

The gateway for New Brunswick is Halifax, Nova Scotia, served by Air Canada (0871 220 1111; aircanada.com) from Heathrow and Air Transat (020 7616 9187; airtransat.co.uk) from Gatwick.

Tour operators include The Independent Traveller (01628 522772; independenttraveller.com; two weeks from £1,899pp), Audley Travel (01993 838 000; audleytravel .com; from £2,085pp; both with flights) and Bridge & Wickers (020 3355 5269; bridgeandwickers.co.uk; from £1,500pp, without flights).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments