The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Le Corbusier in France: On the trail of a controversial concrete king

Fifty years after his death, Le Corbusier's creations are as exciting as ever. Christopher Beanland visits two of the best in Marseille and Beaujolais

Mottled white high- rises sprout from muddy brown mountainsides like smashed-in teeth. The mistral tries to knock me off balance as I take photographs of Marseille's seething skyline. The first time I saw Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation – flouting its primary-coloured balconies as if it were a 3D Mondrian painting – was through a greasy coach window in 1994 on a school exchange trip to France. It took me 20 more summers, finally, to get up here on the roof. In one ear I can still hear Madame Hamilton warning us about the many ways that British children can get into sticky situations in France's louche second city.

The new middle-class residents moved their crates of Le Creuset into Unité (aka Cité Radieuse, the "radiant city") in 1952, and that first sunset glass of Bandol on a balcony slathered in red, yellow or blue must have seemed exhilarating. There weren't any buildings in the wrecked post-war world that looked like this – least of all in the sleepy south of France or its capital – jump-started to life by the people and goods (both legitimate and less so) imported from French North Africa into Marseille's port.

Le Corbusier had previously whipped up pads for the wealthy, such as the suave Villa Savoye in Poissy; but Unité offered utopia for the people. This apartment block was his attempt to connect with a new post-war world of state socialism and technological progress. The U-turn was no surprise. The 20th century's most celebrated Modernist architect – who is being fêted around France this summer, 50 years after his death, with exhibitions such as The Measures of The Man at Paris' Centre Pompidou – created many of them.

Born in the Swiss Jura in 1887, Le Corbusier switched sides to become fully French in 1930. He worked for Petain's collaborator Vichy government during the Second World War (a disquieting new book, Le Corbusier: Un Fascisme Francais – claims he was even more of a fascist than previously feared), but he also tried to build an elephantine Palace of The Soviets in Moscow. He binned his birth name, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris, and took his grandfather's surname, Le Corbusier, or "The Crow", and must have amused himself with its image of cunning and flight.

"He had," said Jonathan Meades, in his most recent BBC outing, Bunkers, Brutalism, Bloodymindedness, "all the usual qualities of a big-time architect: paranoia, vanity, startling selfishness, egotism, resentment". Meades evidently wasn't too rattled by Corb though – he moved into the Unité after pulling an about-turn of his own, ditching a more stereotypical "Brits abroad" farmhouse in Bordeaux.

As I explore Unité's gloomy corridors, illuminated only by skinny uplights above green or red doors, I hope I'll bump into Meades lugging baguettes and sardines home from the épicerie. The building is in good condition and flats sell for hundreds of thousands of euros.

During an interview about his documentary, Meades was quick to dissuade me from lunching in the Unité's own restaurant, but it's there for completists; as is the Hotel Le Corbusier, which uses a handful of the apartments as bedrooms. The unit, which once housed a grocer's, looks forlorn, but there's a book-shop and some offices (especially architects'). All these "services" are found on a floor halfway up, which gives Unité the feel of being a vertical village. J G Ballard deliciously destroyed that communalistic vision in his 1975 novel High Rise, which must have been partly inspired by this building.

Down at ground level, the sweeping porte-cochère and concierge desk feel more mid-range hotel. But you should venture under Unité's skirt – and look up. Between the elephant legs, the underside of the building looks wonderfully flabby. Which makes it all the more remarkable that it balances on these stocky (in archi-parlance) piloti.

But Unité's biggest treat is her roof. There used to be a running track around the edge, a gym, and a kindergarten. The communal terrace has since been bashed about a bit and has lost something of that everyman social spirit in its recent transformation into the Mamo Gallery by the local art lord Ito Morabito.

The plus side is that snoopers are now allowed up here for a paltry €5 (£3.70) to see art, panoramic Marseille views, and the building itself. The works revolve: I saw distance-distorting mirrors by the Parisian Minimalist Daniel Buren, but a giant bust of Corb – sporting trademark round glasses – has also featured. The roof is crowned by huge chimneys which underline how the building acts like a graceful living sculpture.

Corbusier connoisseurs could move on next to the other Unités that he built in Nantes or Lyon's outskirts, or to Notre-Dame-du-Haut Chapel in Ronchamp, Franche-Comté (so good the Chinese built a life-size copy in Zhengzhou). Or to the Maisons Jaoul in Neuilly-sur-Seine, near Paris – small, bricky houses shaped like a railway caboose. But having started at the first real super-sized classic, I'm keen to see his last important work. I take a TGV from Marseille's hot-blooded Gare St Charles to Lyon's more rarefied Gare Part-Dieu, and after a Metro ride, I pick up a chuntering tram-train which plods west towards the vineyards of Beaujolais. I alight in L'Arbresle, just outside Lyon's suburbs, where summits rise, and lowing brown cows unashamedly stare at lone Britons on eccentric concrete conquests through the Rhône-Alps countryside.

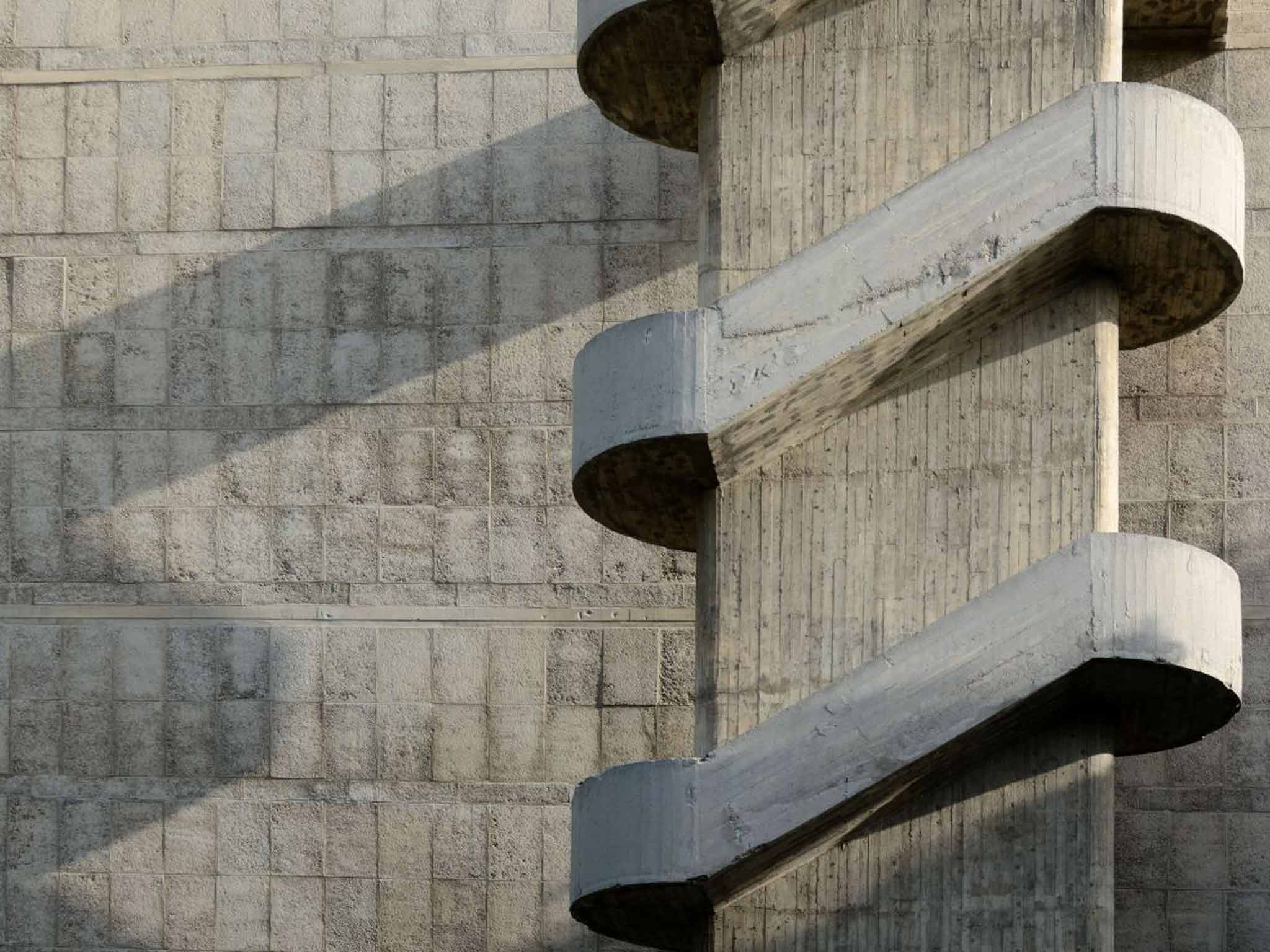

The hike from the station in the valley up to the Couvent de la Tourette is bracing – past bucolic homes, boulangeries and fields; but the reward is seeing a Brutalist classic in its unnatural environment. Concrete is for the city, surely? But here in the hills, Le Corbusier and his partner, Iannis Xenakis (another Francophile who moved here from Greece), built a monastery with an unrepentant, rock-hard finish. The juxtaposition between the building and the emerald grassed slope it manages not to slip off is exciting.

You can only explore the inside of Corbusier's last big beast on a tour, and I make it by the skin of my teeth to join one led by Armelle Le Mouëllic, a friendly architecture student from Grenoble who delivers each bit in French and English. She and I talk about our love for modern architecture and she explains that she's staying in one of the monks' rooms (and that "there's no wi-fi").

Le Corbusier and Xenakis built this place for trainee Dominican monks, who arrived in 1960. It must have been peculiar for them to be living through the maelstrom of the Sixties in this ultra-modern building, yet practising as their brethren had for centuries. There aren't many luxuries, but there are three spaces that blow you away with their simple intensity. The undercroft of the whole building is one – because it's jacked up on piloti, there's a massive wedge of strange space down there. The refectory, with its windows designed by Xenakis as a kind of repeated run of musical notes (he was also a composer), is another.

But Le Mouëllic saves the best for last. The church is the real show-stopper. A huge, sober box – dark except for the sun that pokes in through the slashes Corb created. In the chapel, three skylights glow red, white, and black against the gloomy interior. The thrilling result reminds me of a Mark Rothko painting.

Le Corbusier's life was almost at an end when La Tourette was finished. Five years later, he drowned off Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, near Monaco, and was buried overlooking the Mediterranean. I stop on the way back down to L'Arbresle and turn back to look again at the muscular monastery from a distance and to remember that, even after his death, Le Corbusier exerted a powerful global influence upon architects who sought to recreate cities from Boston to Birmingham, from Kyoto to Cologne, in his image.

The results varied. Recently though, Brutalist buildings dreamt up by copycats have found love rather than loathing – as people appreciate the unusual poetry of concrete. But France never lost faith with its delinquent adopted son.

Le Corbusier's best buildings are here, so too is his most appreciative audience.

Getting there

Christopher Beanland was a guest of British Airways (0344 493 0787; ba.com), which flies daily from Heathrow to both Marseille and Lyon. SNCF (sncf.fr) trains link Marseille and L’Arbresle, via Lyon.

Staying there

He stayed at the Hotel Victoria in Cap Martin (hotel-victoria.fr), Mama Shelter in Lyon (mamashelter.com), and Collège Hôtel in Lyon (college-hotel.com).

Visiting there

Couvent de la Tourette (couventdelatourette.fr) tours €7 (£5.20). Until 30 June on Sundays at 2.30pm and 3.30pm; 1 July to 31 August on weekdays at 10.30am, 2.30pm and 4pm, plus weekends at 2.30pm and 4pm.

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments