China's slow economic transition may hold back its dominance over the US

China has rejected rapid privatisation of state-owned enterprises in favour of a gradual shift

China has chosen continuity in politics, but what does it mean for the Chinese economy?

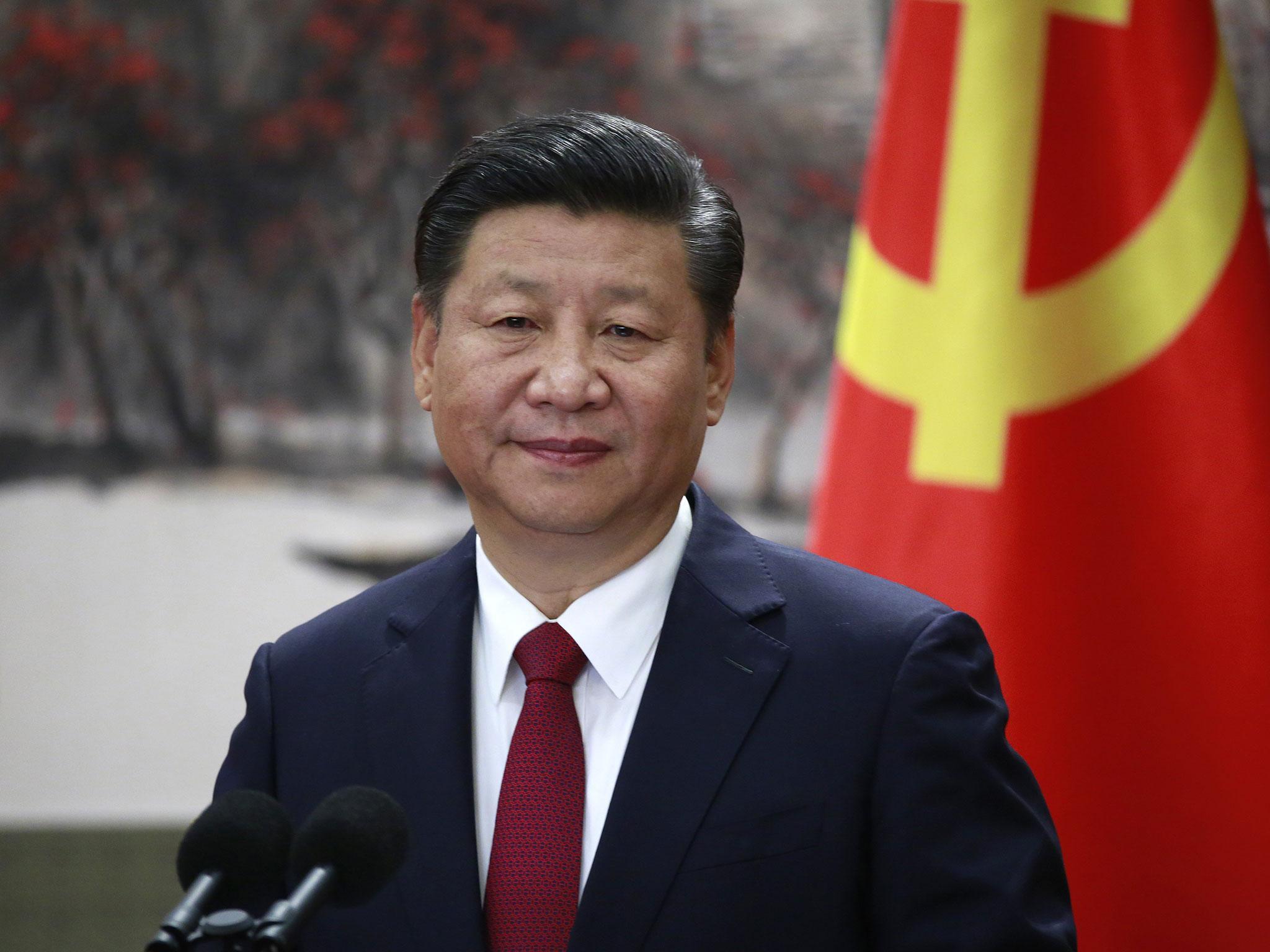

The Party Congress has ended and the new Politbureau and its Standing Committee were elected on Wednesday. As expected, Xi Jinping remains General Secretary and Li Keqiang remains Premier. The other five members of the PSC are all relatively old, so there is no obvious successor yet to Mr Xi. He has also been elevated to the same position as Mao Zedong in the party constitution, making him in effect the most powerful leader since Mao Zedong.

From an economic perspective the question is a simple one: does this consolidation of power speed up or slow down the pace of economic reform in China? The country remains on track to become the world’s largest economy, passing the US in the next 10 to 20 years. Indeed, if you calculate the size of the economy in terms of purchasing power parity rather than market exchange rates, it already has.

More of that in a moment. But it faces at least four huge problems: its ageing population; environmental concerns; the need to run down state-controlled enterprises and build up market ones; and the shift from manufacturing to services.

The central government cannot do much about demography, though it has acknowledged the issue and is easing the one-child policy. It has to do more about the second and is already trying to do so, for example by promoting electric cars. As for the last two, this is where policy matters.

State-owned enterprises, and there are about 100 of them, are less efficient than privately owned ones. According to official figures they produce an average return on assets of 2.9 per cent last year, against one of 10.2 per cent for the private sector. That is not entirely the fault of their managers, for they are often directed to do things for the authorities’ social objectives that make them less profitable: for example maintaining employment and investment rather than slimming down when demand falls.

China has rejected rapid privatisation of these companies in favour of a gradual shift, perhaps passing three or four a year into ownership by state-owned holding companies, which can then gradually be sold to the public at some later stage. Why? It wants to retain control of the economy, as it has for the past 40 years.

It is hard not to feel sympathy for this gradual approach, for China has managed to avoid the chaos that engulfed Russia. But a slower transition will probably mean slower growth.

The shift from manufacturing to services is a parallel one. This is not something that countries have much control over. Germany has maintained a somewhat larger manufacturing sector than other G7 economies, but not much. In every advanced economy the shift is taking place, with manufacturing typically between 10 and 15 per cent of GDP. In China manufacturing is still nearly 40 per cent, but was passed by services (now more than 50 per cent) back in 2012.

Services are by their nature different from manufacturing, and in particular harder to fit into a command economy. So the Chinese government’s power over the economy will tend to fall as a result. So there is another dilemma: promote the shift (as for example the Shanghai municipality is doing) and you accept you cede control, or seek to retain control by resisting it.

We know enough about economic development to be pretty sure that giving greater power to the market will lead to faster growth. China is the classic real-world model of this. But social order matters and it may be sensible to go for a slower transformation of the Chinese economy if that enables the country to avoid overly disruptive change.

In any case, China almost inevitably passes the US to become indubitably number one. When? Well, the famous Goldman Sachs BRICs report calculated that this would happen about 2027. More recent work by HSBC suggested it would not be until about 2040. But if it were the earlier date, and were Xi Jinping to have a third term as General Secretary, that would be at the end of his period of office.

At the moment there is a long way to go. Last year, according to World Bank data, the US GDP was $19.6 trillion; China was $11.2 trillion. A lot, good or bad, can happen in a decade. But let’s do the sums. Suppose the US were to grow at 2 per cent compound its GDP in 2027 would be about $24 trillion, and if China were to grow at 7 per cent it would be around $22.5 trillion. So China would not quite be there, but it would snapping at the US’s heels.

Maybe those growth projections are too pessimistic for the US and too optimistic for China, but you can see the prize: be leader of China when it becomes the largest economy in the world. No wonder Xi Jinping would like to stick around.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks