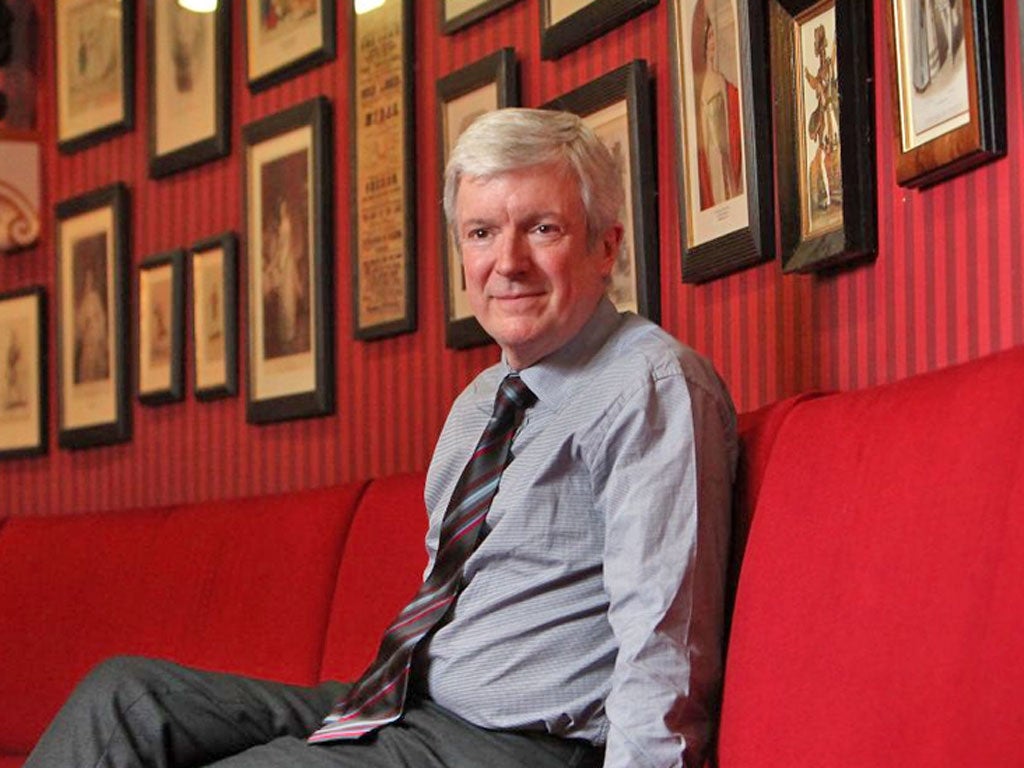

As the new Director General of the BBC, Tony Hall should champion Royal Opera House elitism

A focus on quality above all else would help the BBC out of its rut

It is probably a fair bet that Tony Hall never dreamt, when he upped sticks for the Royal Opera House after failing to land the top job at the BBC, that more than a decade later the Director-General’s chair would be his.

Nor can he have imagined that when he was finally offered the position he had coveted as a still young-ish executive, he would be spared the interminable rounds of shortlists and longlists and selection boards, not to speak of the public speculation, that attend the making of senior appointments at the BBC. In a real crisis, it seems, even ponderous old Auntie can get her skates on. Let that be a lesson for public bodies generally, even in less stressed times.

It would be pleasing to learn that, in their accelerated search for a new Director-General, the BBC Trust had called in all the shortlists from yesteryear, established who was still around, considered who had used their subsequent years most interestingly and productively, and reached a preliminary decision accordingly. Less pleasing would be to find that a fast-tracked search had ventured no further than London Clubland and the old school tie – even if the school concerned was the then direct-grant Birkenhead School, rather than Charterhouse or Eton.

But a swift appointment was highly desirable, not least because prospective internal candidates, including the caretaker Director-General, Tim Davie, needed to know where they stood. The internal jockeying that was already beginning – with everything Davie said being interpreted as a bid for permanence – risked entrenching the Savile scandal damage. Mainly, though, it was the scale of the meltdown in confidence inside the BBC and the persistent talk of falling public trust in the Corporation that dictated speed. The only hitch is that, presumably because of contractual obligations, Hall will only take up his new post in March. Maybe some sort of special dispensation on notice periods should apply to the transfer market in really top jobs.

Calibre

At least as desirable as speed, however, was to find someone of proven character and calibre. It can be argued that the pendulum in BBC appointments has always swung too wide, with each appointment reflecting the perceived failings of the previous incumbent. Thus it was, perhaps, that Hall (then the insider) lost out to Greg Dyke, the ebullient outsider from the commercial world, who promised to “cut the crap”, as he saw it, of jargon and bureaucracy introduced by his predecessor, John Birt. Thus it was, too, that Mark Thompson, the seemingly mild-mannered news executive and quintessential BBC man, was preferred as the ship-steadier after Dyke resigned, in the BBC’s last crisis of confidence, over the Hutton Inquiry.

Such was Thompson’s success in this particular respect – though not completely in the broadcasting – that continuity was the priority when George Entwistle, another quintessential BBC man, with an early career in commercial magazine journalism, was appointed to take over earlier this year. But it turned out that his relatively quiet life had equipped him ill for the cataclysm over Jimmy Savile that engulfed the Corporation within days of his claiming his office at Broadcasting House. He was slow off the mark; he had next to no public presence, and he was granted no time at all to acquire one. After 54 mostly unhappy days, he was out.

That is the context in which Hall’s appointment has to be seen. In 1999, the BBC’s desire for a high-profile outsider with a sharp tongue and a hard-scrabble commercial background left Hall looking for other opportunities, despite his impressive portfolio of innovation at the BBC, which included the Parliament channel, the News channel, Radio Five Live, and the News website – all of which, it deserves to be stressed, have stood the test of time. Now, with a successful 12 years at the Royal Opera House behind him, Hall can boast a whole new clutch of achievements that prove he can swim in the real, commercial world and flourish somewhere different from broadcasting.

For a self-selected group of licence-payers, who immediately took to the internet chatrooms to criticise the appointment, Hall’s time at the helm of the Royal Opera was seen as a big negative, almost regardless of what he had done there. It was lumped together with his schooling and his Oxford degree, and summed up in one word: “elitism”. “Oxbridge-educated champagne socialists the lot of them,” was one of the more printable comments, supplemented by outrage at the price of tickets at Covent Garden.

Quality

An injection of unapologetic elitism, à la the Royal Opera, however, may be just what the BBC in its present depressed and introspective state needs, along with reforms of the sort that Hall has made during his tenure. For there are ways in which the Royal Opera in the late 1990s might be seen almost as a microcosm of the BBC today: a national institution stuck in a rut; a once world-class establishment, let down by patchy management, outdated facilities, unwise spending, a certain cultural parochialism, and a lack of confidence about who really constitutes its audience in modern Britain.

Of course, the BBC is a far bigger and more complex undertaking than the Royal Opera House, but the resemblances in terms of what should be done are compelling. One is a focus on quality above all – for while the BBC’s domestic programming remains second to none, what is offered by the commercial broadcasters in the digital age has been catching up, as has the competition internationally. The BBC cannot afford to rest on its laurels, least of all in the global market, where what is at stake is not just market share but national image.

The second is to streamline management, introducing much clearer, and shorter, lines of editorial responsibility and editors who regard it as their job to see things, rather than not to see them. Entwistle will forever be an object lesson here. As a former BBC executive, Hall will doubtless be aware of where surplus bodies are buried.

And the third is to review exactly what the BBC should be doing and who it should be doing it for. As a former head of BBC News, Hall will need no persuading of the primacy of news as the standard-bearer for BBC quality – and like opera, news is expensive. At the Opera House, though, Hall also tried to broaden the audience, by satellite transmission among other things, while also upgrading and making better use of the unique and atmospheric premises.

The next Director-General has to do something similar. In the future, the BBC will have to justify the licence fee even more than it does today, as more viewers decide to pay for additional choice. If that means the BBC deciding to define for itself a more “elitist” purpose, Hall will have no reason to apologise. As he showed at Covent Garden, it is quite possible to be “elitist” in a very good way.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments