Steve Ballmer’s theatrical farewell to Microsoft: Is fervour a help or hindrance to business success?

Embarrassing? Yes, but this goodbye showed the strengths of US business

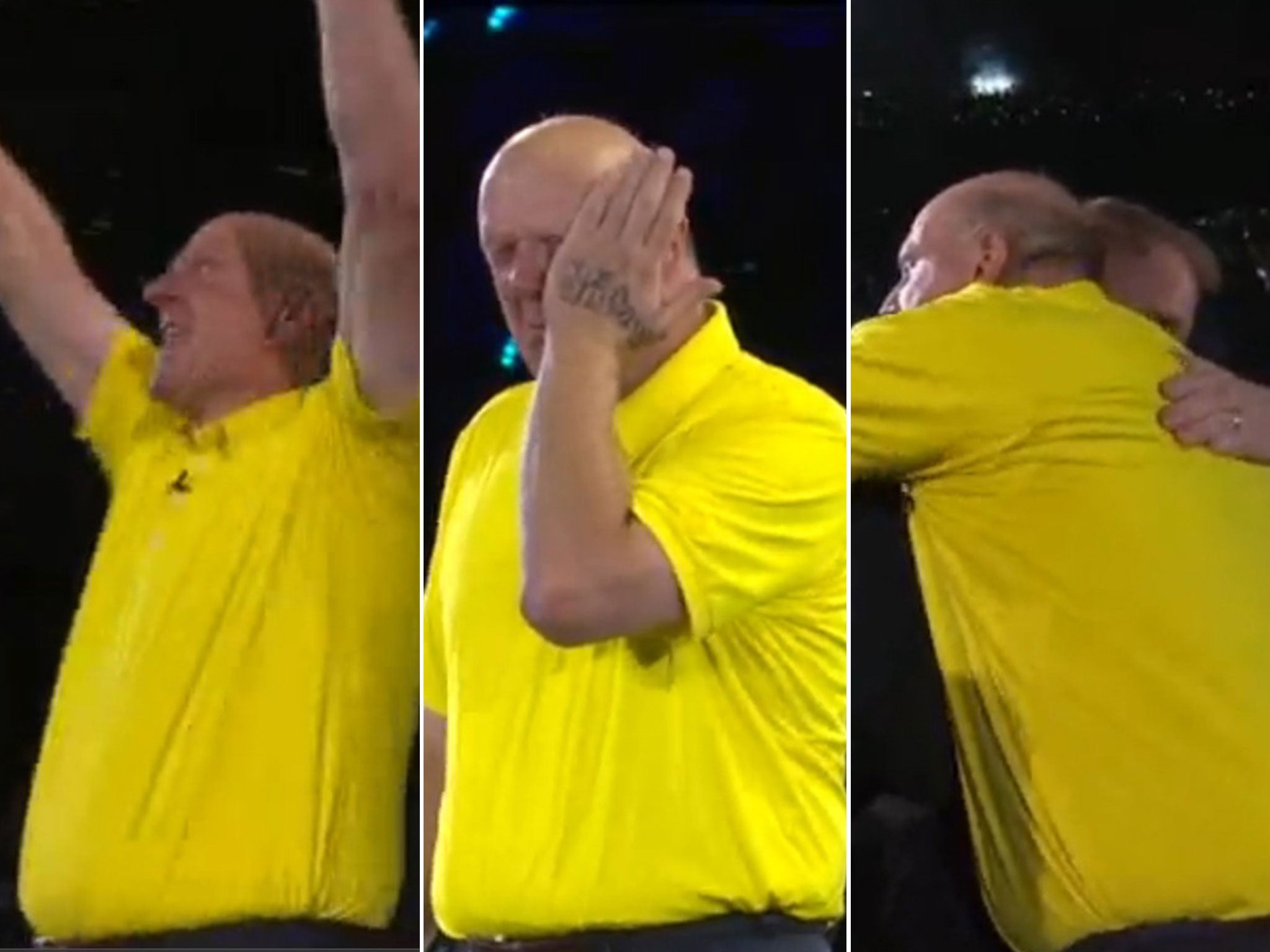

It is of course profoundly toe-curling and for at least three reasons, yet the Dirty Dancing departure speech of Steve Ballmer, the soon-to-be outgoing chief executive of Microsoft, tells us a whole heap about the success of American business, and indeed the wealth of our modern world.

If you haven’t seen it, waste a few moments Googling him for the clips on YouTube. And there in that sentence lies part of the explanation of how Microsoft has changed the world. Neither of those technologies, which we now regard as the normal fabric of life, could have existed without the technical competence, and more important, business drive of the company for which Steve Ballmer has worked since 1980.

There were personal computers then, for the Commodore PET, the Apple II and the Tandy TRS 80 had been out for a couple of years. But it was IBM and Microsoft that changed everything, with the PC in 1981. As for Steve Ballmer, sure he was number two to Bill Gates, but businesses with an inspirational founder need the competent number two to run them.

The three elements of that departure speech that we Britons (and I suspect a lot of Americans) find most off-putting are the absurdity of an overweight middle-aged man prancing around a stage; the assertions about the ethical nature of the company and the contribution it had made to “helping people lead great lives”; and the adulation of the 13,000 employees in the audience, cheering their Great Leader. Yet all three in their way exemplify American corporate excellence, and we should at least acknowledge that.

The prancing? Well, it does no harm. It is not like a speech by a politician designed to whip up hostility towards other citizens, such as immigrants or bankers. Its aim is to imprint the notion that the chief executive is on the same side as the employees, which since many of them also have stock options, he probably is.

Different leaders use different devices to encourage or drive their colleagues. Some use their charm; some use their intelligence; and some are simply unpleasant: Fred Goodwin was renowned for making executives at Royal Bank of Scotland cry, though they must have been a bit wet to put up with that.

Steve Ballmer has done well for himself, for he is worth some $18bn, and if he chooses to use enthusiastic energy to get people to do things for the company, so be it. We should not sneer at enthusiasm.

The second element, the “you work for a great company” line, may jar too. Microsoft is a bit of a wounded giant nowadays, as computing has gone mobile and its operating systems have been relatively slow to gain traction there. It has also in the past been pretty brutal in the way it managed its dominant position, buying up potential competitors or trying to put them out of business.

But it is the US corporate giants that have given us the kit that runs our daily lives. This article is being written on a Hewlett Packard keyboard and a Dell computer running Windows and Word, and put into format using Adobe Systems software – all American.

The point about this is that the US has exported its technology to the world. Its economic system, for all its shortcomings, has delivered stuff that changes everything. No other country could have done this. Of course the US has done very well out of this for itself, but there is a generosity in that the world economy would be much less efficient had we not all had access to its technologies.

And the third thing, those cheering employees? Well, it is not as though they have been bussed-in for the cameras. This is not North Korea. Corporations need people who are loyal, and many individuals feel loyalty to the people they work with.

Look at a crack Army regiment, or a top-ranked university department. Look too at how upset people become when they feel their work is not properly valued. Company fortunes rise and fall, and the churn at the moment can be particularly harsh for people who find it difficult to adapt to rising insecurity.

The freedom to chop and change jobs, building one’s human capital as you do so, is the positive side of flexible labour markets, but the flip side can be frightening too. If employees want to assert their support for a chief executive who has been with the firm for 33 years then they are showing a natural human reaction. And if American companies try harder at building rapport with their people than British or European ones, what’s wrong with that?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies