Mary Dejevsky: You can mislead a minister, but don't make her a laughing stock

It is not hard to discern a good deal of political opportunism behind all the noise about Abu Qatada

The mood of the House of Commons can turn on what used to be a sixpence, but in current circumstances might more appropriately be designated a euro. On Tuesday, Theresa May drew whoops of delight, when she announced that, while the Home Office would not be appealing against the European Court of Human Rights ruling on Abu Qatada, Osama bin Laden's alleged chieftain in Europe had been rearrested in preparation for his removal.

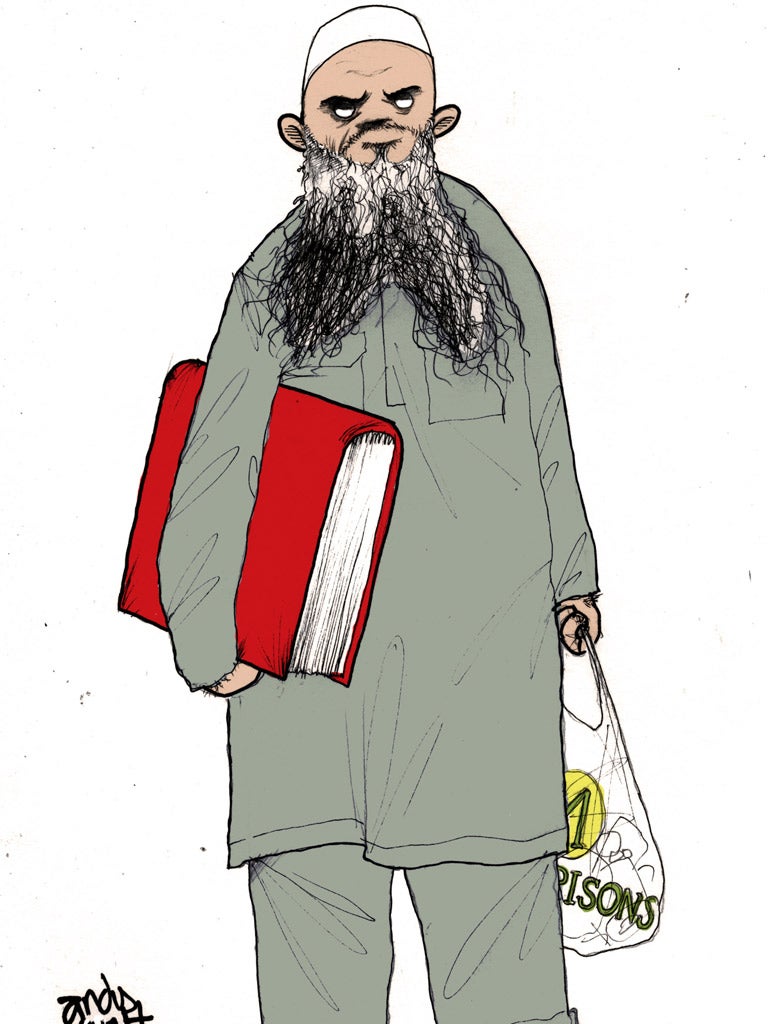

By yesterday, though, a distinctly less triumphal May was being howled down by those very same MPs for a supposedly almighty cock-up over dates that could take the European Court proceedings almost back to square one. The picture of the bearded Qatada being bundled on to a plane, that had cheered every minister but 48 hours before, faded once more into the distance. It would be months, if not years, if ever.

And the indignation fitted all too well into the fetid political atmosphere and the gathering view of a government prone to accidents of its own making. Instead of rescuing the Government from its Budget tribulations, as perhaps had been hoped, the Qatada affair seemed merely to be adding another link to the chain of misjudgement and incompetence. Against the background of the "granny tax" and "tax-dodging" philanthropists, a deportation that had failed for lack of arithmetic and calendar skills was simply par for the course.

Here was a government that had lost its impetus, flailing around, out of its depth. It offered ample material for Ed Miliband to score points off David Cameron at the first post-Easter Prime Minister's Questions and for Yvette Cooper to worst Theresa May, as she did yesterday, over the fact that she was out partying with television stars, even as Qatada's lawyers were submitting his 11th-hour appeal.

Nor has it helped that the return of the Qatada affair coincides with a conference of European Court representatives in, of all places, Brighton. An assembly that the Government had planned as the centrepiece of its efforts to refashion the much-maligned court in a more British image, was threatening to slip out of its control even before it began, but is now set to register little beyond British hostility. In sum, the Government has found itself in the worst of several worlds. It was possible to imagine a told-you-so smile hovering about the lips of the Justice Secretary, Kenneth Clarke, as he went on the BBC Today programme yesterday in a chivalrous effort to help the Home Secretary out – but not, it seemed, too much.

Yet the impression that the Qatada affair belongs with the Government's latest run of worries is at once to exaggerate and to underestimate the problem. It exaggerates it, because the Home Secretary never suggested that deporting Qatada would be instantaneous. When she addressed the House of Commons on Tuesday, she pointed out that Qatada could appeal and that, if he did, the legal wrangling could go on "for many months". She was quite explicit. But her caution was largely drowned out by the wishful thinking of her audience. They wanted to believe that Qatada was not only back in prison, but entering his last two weeks in the UK. She never claimed that, and should not now be pilloried as though she had.

Yes, it makes a difference that the sort of appeal she was talking about – to the Special Immigration Appeals Commission court, specifically against deportation – is not the sort of appeal that Qatada has actually lodged. He has applied to the Grand Chamber of the European Court, and is challenging the lower court's view that he would not face torture if returned to Jordan. Given that the lower court found that this would not be the case, however, the UK government's prospects of winning, even if Qatada's appeal were heard, would seem reasonable and even good. All in all, the Home Secretary has shown commendable patience with the protracted court proceedings so far, and she is right not to lose her cool now.

To this extent, the terrific fuss being kicked up by MPs on both sides of the House yesterday seemed excessive. Of course, there is carpet-chewing frustration that Qatada has yet again postponed his rendezvous with justice. But it is hard not to discern a good deal of opportunistic politicking behind the noise – from Labour, who have found a human rights issue where they can solemnly join the crowd, and from Eurosceptic Conservatives determined to damn Europe and all its works. Whether they necessarily appreciate the crucial distinction between Brussels and Strasbourg hardly matters.

Where the significance of the Abu Qatada problem has been underestimated is not in relation to Strasbourg, but in relation to the Home Office. If there was any doubt about the date and time when the appeal window closed, the Home Office should have been

aware of it and counselled the Secretary of State to play safe. If, as it appears, she was allowed to jump the gun with the re-arrest and resumption of deportation proceedings against Qatada, this was an error of colossal proportions. Not just because the Home Office may have got the date wrong, but because the Home Secretary was made to look foolish.

There are many "ifs" here. If Qatada's lawyers were aware, or made aware, of the extra day, why not the Home Office? And if the European Court in Strasbourg was giving contradictory advice, this must surely be weighed by the court when it considers the admissibility of Qatada's appeal. If, on the other hand, Home Office lawyers drew their own conclusions about the cut-off, or even spurned advice from Strasbourg, this smacks of arrogance laced with negligence – a pernicious mix regrettably not unheard of in the upper reaches of the Civil Service.

In that event, two things might happen. Theresa May might tender her resignation on the grounds that the minister takes ultimate responsibility for a mistake – even if she only acted on her civil servants' advice. That would doubtless be Labour's preference, at once perpetuating the scandal and removing an able minister.

Or, far better, the Government could make the affair into a pretext for an overdue restructuring and purge at the bloated Home Office, such as May embarked on all too half-heartedly with the UK Border Agency. Civil servants can be allowed the occasional mistakes, but they cannot be allowed to make their minister a laughing stock. Heads must roll – but those heads should not include hers.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies