Mea Culpa: The strait and winding path to everlasting life

Points of style and usage from this week’s Independent

In an article about knife crime we used the phrase “straight and narrow” in our rendering of the lyrics of a song by Joshua Ribera, the Grime artist known as Depzman, who was killed in a knife attack. That is the usual spelling these days of the phrase meaning an honest way of life, but it adds something to know that it was originally “strait”.

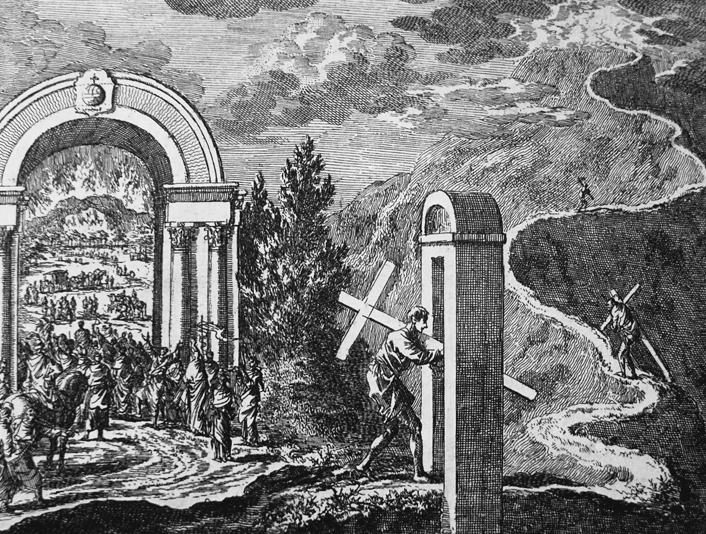

It comes from the King James Bible: “Because strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it” (Matthew 7:14). Strait is an old word that means narrow, which means the phrase in its early form was tautologous – a bit like “null and void” or “ways and means”. As you can see from the biblical engraving above, the narrow way that leads the right way could be anything but straight.

Strait survives mainly as a word for a passage between two bodies of water, and in phrases such as dire straits, straitjacket and strait-laced. It comes from Old French estreit tight, narrow, from Latin strictus, drawn tight, which also gave us strict. Straight on the other hand is a form of “stretched”, which comes from a Germanic root.

“Straight and narrow” may have been a mistake once or, if we prefer, an unconscious improvement of a duplication, but it has been the more frequently used form since about 1870.

So that’s fine. But what a shame to use “knife crime epidemic”, a deadening cliché, in the article’s sub-headline.

Surplus syllables: We reported this week that women at risk of breast cancer are shunning “preventative” drugs for fear of side effects. As Norman Mills wrote to point out, a preventative can be a noun, but is needlessly long as an adjective, when “preventive” will do.

This is one of a group of words that tend to acquire extra syllables, such as orientate, disorientate and disassociate. You can see why people just put “dis-” in front of “associate” when they want to say the opposite, but the “a-” is already a prefix (from Latin ad-, to) to a Latin root, sociare, join together (from socius, companion).

Orient, disorient and dissociate are all better, I think, because the longer forms can be disorienting for the reader.

Waiting for the rapture: In the report of Emmanuel Macron’s speech to Congress in the Daily Edition this week, we referred in a sub-headline to the French president’s “rapturous speech”. As Philip Nalpanis pointed out, such a speech would be one that expressed great pleasure or enthusiasm.

Some of Macron’s hand-holding with Donald Trump may have been a little sick-making, but the speech itself was a serious and hard-hitting oration spelling out where he disagreed with US policy on climate change and free trade.

We probably meant to refer to its reception by members of both houses of Congress – they did seem to be standing up to applaud almost as often as the Conservative Party conference did for Iain Duncan Smith in 2003, which was indeed rapturous, if insincere.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments