Why we need Jeremy Corbyn's National Education Service

It's been portrayed as a recipe for dystopia, in which over-centralisation, lack of choice and falling standards are the norm – funnily, that sounds a lot like what we have at the moment

One of my first jobs was teaching a university access course at a primary school in Anfield, in which young mums and dads came back into education while their children were learning or playing in the same building. I've often thought of it as an image of how our education system could be better organised, bringing together early years, school, further and higher education.

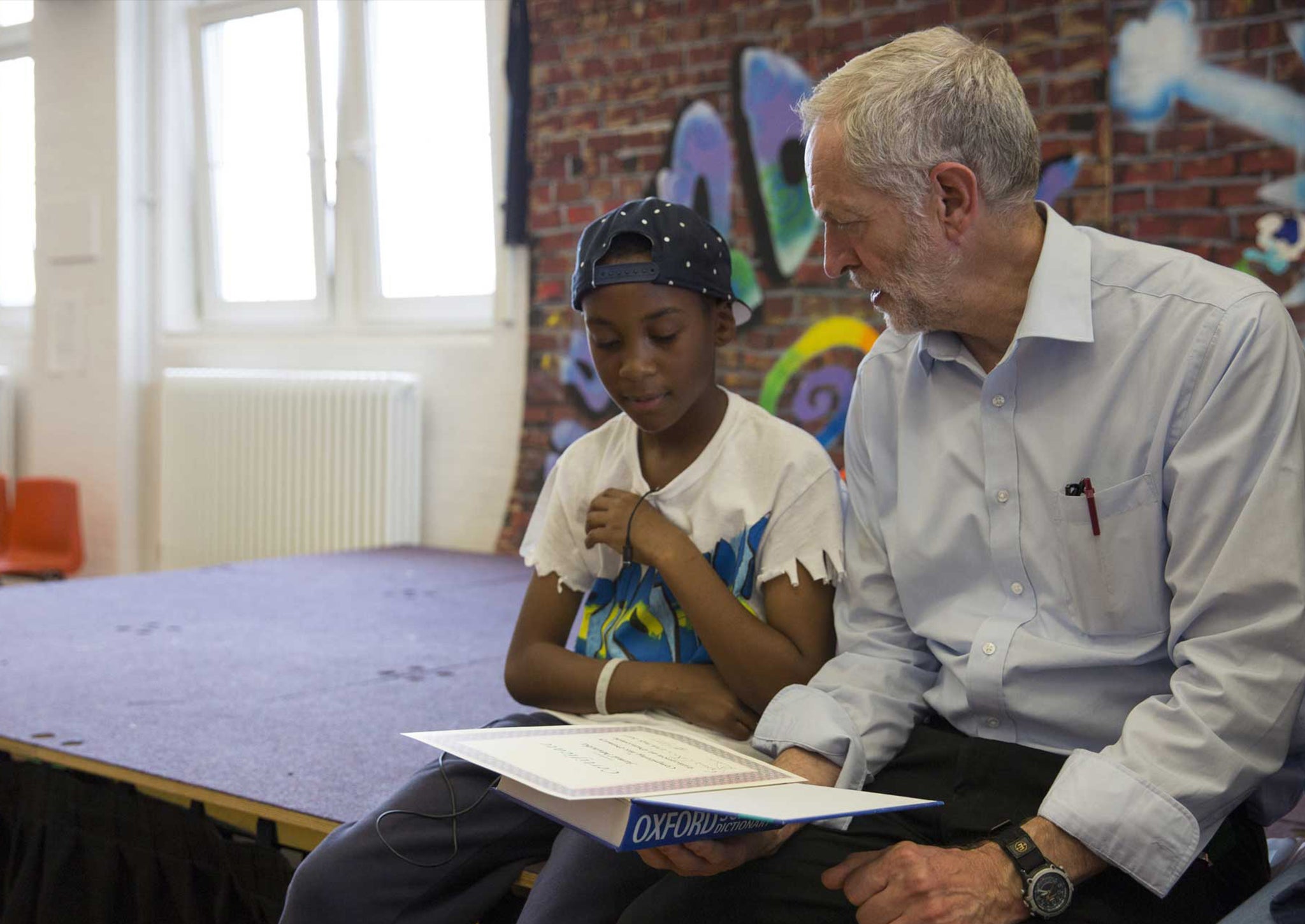

The idea of a National Education Service (NES), floated by Jeremy Corbyn during his leadership campaign, suggests this is possible. He said he wanted a genuine “cradle to grave” service. "[It] will give working age people access throughout their lives to learn new skills or to re-train," he wrote in July. "It should also work with Jobcentre Plus to offer claimants opportunities to improve their skills, rather than face the carousel of workfare placements, sanctions and despair." It didn’t get a mention in his speech to the Labour Party conference, but he and Lucy Powell have both said they are committed to bringing all schools back under local authority control.

Like many of Corbyn's ideas, an NES is easy to caricature. It has even been portrayed by some as a recipe for dystopia, in which over-centralisation, lack of choice and falling standards are the norm.

It's funny, because that sounds a lot like what we have at the moment. We have had 20 years of the centralised, standardised National Curriculum and the undermining of local authority control. Yet, as the OECD showed in 2013, the pool of highly skilled adults in the UK is shrinking. In a survey of 24 countries, the UK performs third best for literacy in the 55-64 age group, but in the bottom three for 16-24-year olds.

Young people therefore need opportunities to re-train. Yet, as Corbyn pointed out, there's been a 40 per cent cut to the adult skills budget since 2010. Further education has been devastated – and Vince Cable claims he was encouraged to finish it off.

Our universities are also becoming more uniform, at a time when we need a diverse and flexible system. George Osborne claims that the number of students in higher education has gone up since 2010. This is only true if you don't count part-time students, whose numbers have dropped 41 per cent. If you take full- and part-time students together, there has been a 20 per cent drop – a fall of 174,000 students. Part-time students are exceptionally diverse in age, socio-economic background and life histories – so the impact is profound.

How would an NES help? One story shows what is possible. In 1987, after serious industrial disputes, the car manufacturer Ford put aside 0.3 per cent of its annual wage bill for an Employee Development and Assistance Programme (EDAP). Members of staff could apply for up to £200 per year for learning that was not related to the business, whether it was an exercise class or a university course.

The EDAP scheme's benefits have been wide-ranging: improved staff retention, reduced absenteeism, better industrial relations, and knock-on effects on work-based learning - and even on family learning schemes.

How does this relate to an NES? Firstly, systems matter. A genuine learning culture - in which even "pointless" learning is encouraged – can help achieve tangible outcomes in skills and productivity. If we want to measure education, we need more than the blunt instrument of test results.

There are also gains for mental health, which is another Corbyn priority. Vince Cable has spoken movingly of how his mother “saved her mind” after a serious breakdown by taking adult education classes. I have met many students who say the same.

Secondly, an NES could reduce centralisation and increase collaboration. Decisions in the Ford scheme are devolved locally, and it shows that the benefits of learning are communal. An NES similarly could establish learning cities and regions, in which different agencies would work together to offer provision and establish local priorities.

Finally, an NES is a pro-business policy. It could provide the learning environment and high-level vocational training that businesses need, plus skills for the self-employed. Corbyn suggested a 2 per cent corporation tax to pay for it, but this should be conditional on significant business input on vocational skills. A Corbyn government could also give significant tax remission if businesses offer meaningful training themselves.

There are huge debates to be had about how an NES would be funded and organised and what role different sectors should play. But if any political party wants to deliver an education system with less centralisation, more choice at all ages, and better results, Corbyn's idea is an excellent place to start.

Tom Sperlinger teaches at Bristol University and is author of Romeo and Juliet in Palestine: Teaching Under Occupation. Follow him on Twitter: @tomsperlinger

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks