James Righton: ‘Klaxons became some kind of karaoke show’

The breakdown of Righton’s band left the musician hating music. But, as he tells Mark Beaumont, with encouragement from wife Keira Knightley, he’s been reborn as a Bowie-styled performer

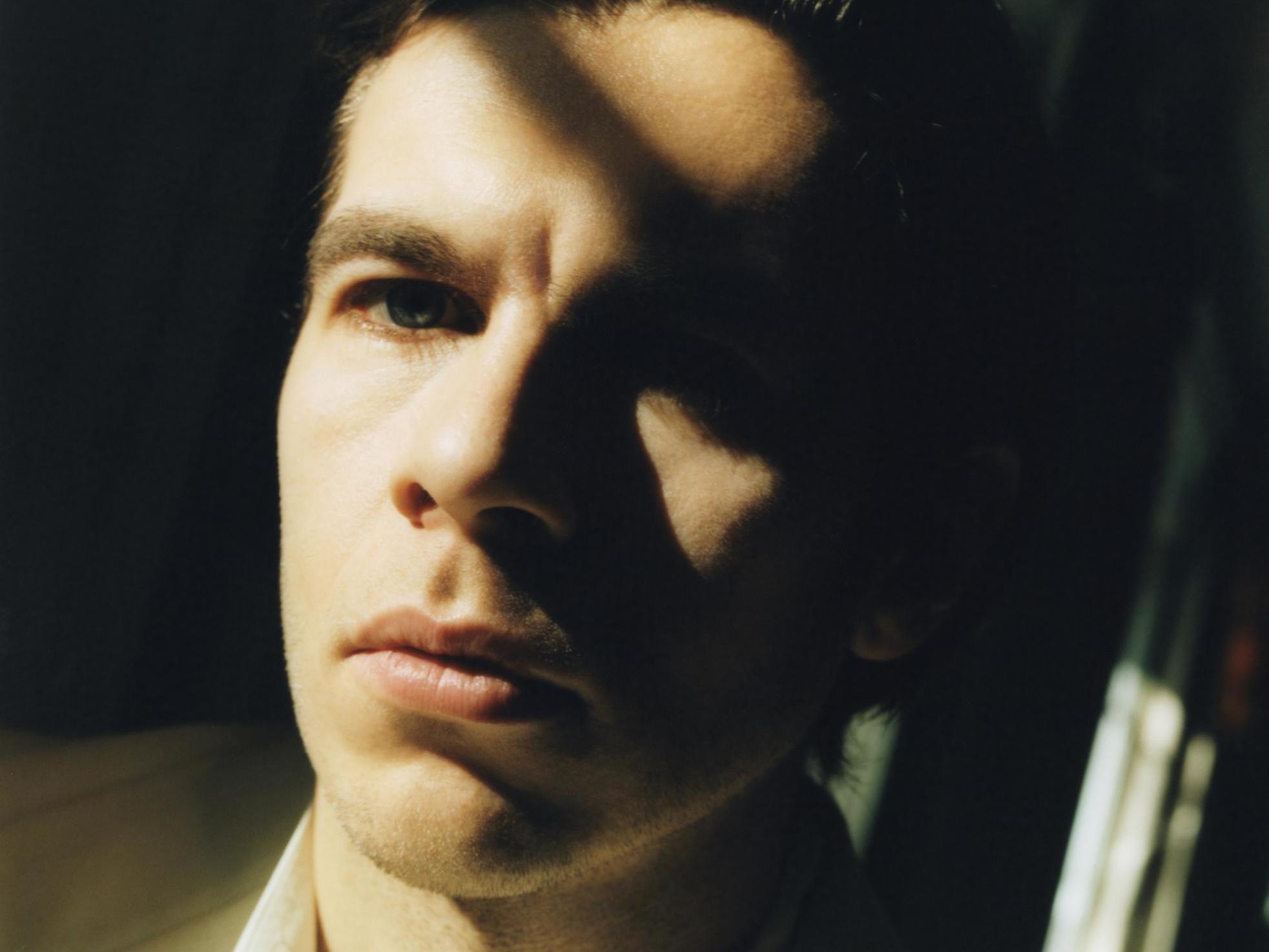

An enigmatic figure in suave, sombre attire scoots inside the café, dark eyes darting, his wide, Germanic lapels raised against the cold. He is wary, perhaps, of being observed. “It comes with being married to a film star,” he’ll later shrug. Is this really James Righton, one-time member of “nu-rave” figureheads Klaxons and now Mr Keira Knightley? Dressed in a woollen trench coat and with louche, slicked back hair, he’s unrecognisable from the garish 20-something who blitzed the Noughties with gamma ray synths, angular barnets and T-shirts like a violent backstreet art attack. His look now is more Third Man than Mad Max, more Berlin ’31 than Shoreditch ’06.

At their late-Noughties peak, Klaxons briefly manned the control deck of alternative culture. They bagged the 2007 Mercury Prize for their “fantasy vision” debut album Myths of the Near Future, performed with Rihanna at the 2008 Brit Awards and inspiring legions of shouty, day-glo synth manglers in their image. Yet they collapsed over two messy and confused subsequent albums and now epitomise a Noughties indie hangover, a fractured neon memory of the nation being briefly intoxicated by MDMA and dazzled by glowsticks before guitar music went south.

With his debonaire, retro-modernist debut solo album, though, Righton has dubbed himself “The Performer”. Is it a means to shed the nu-rave stigma? A disguise? Is it both album title and new persona?

Righton slides behind a table in the north London café, not far from the home he shares with Knightley and their two daughters. With “a persona”, he considers, “you’re probably trying to hide behind something, and I’m not trying to hide behind anything, lyrically at least.” And yet, the white suits he has started wearing onstage as “The Performer” suggest seventies Ferry; Bowie’s Thin White Duke; a musician exploring the codes of showbiz. “I started becoming something ‘other’,” he admits. “The suit became quite transformative in me – onstage, I became more confident and less scared about performing. I felt like I could do it again. I started to think about how as a musician, as an actor, whatever you’re doing, you’re becoming something else when you step on a stage, and the audience is complicit in that.”

The title track of The Performer – a “meta song about the art of performing” that resembles Metronomy rewriting the Cabaret soundtrack – also speaks to the hollowness and discomfort of a performance you feel no part in, of really “putting on a show”. “That’s not me standing there in the light, put it on for the night,” he croons, a reference to grinning and bearing his way through the death throes of Klaxons. “I felt like I wasn’t there,” he says. “It became some kind of a karaoke show or a travelling circus where you’re not really present… you’re doing something and you feel that it’s dying, but you have to go out every night as a commitment. There were times where I didn’t want to be there.”

Five years on from the band’s split, Righton is only now beginning to feel comfortable on his creative feet again. “My confidence was shot from the last three or four years of the Klaxons,” he admits. “We’d gone through such a journey of extreme highs, extreme lows, that by the end of it I didn’t know if I could do it, or wanted to do it. I was lacking in any kind of confidence.” The highs, he continues, were “the first week of the band. The first time we got into a room together in New Cross, all on the dole, and the chemistry was instant – we wrote these songs that became the first album really quick.”

But the lows were hard to handle. “Then the momentum and the hype happened and we couldn’t ever control that. I felt deep down that we were doomed from that point. Whilst it was enjoyable to go on this ride, I’d always look at myself from the outside and go, ‘I would hate this band if I was looking in. I don’t trust things that are hyped.’”

It sounds like a classic case of imposter syndrome. “Massively,” Righton agrees. “I felt guilty: ‘We don’t deserve this’. Also, how are you gonna do anything but disappoint with your next record? Of course, then it affected band dynamics. Some people are more prone to believe the hype, so egos, addictions, drugs, you name it, we did it all.”

As the Noughties indie rock explosion gasped its last breath, and with it the pre-streaming age of music industry excess, Klaxons represented a final hedonistic blow-out, the last great party in town. “It was out there,” remembers Righton. “Looking back, it was pretty extreme. We all had different issues that we were probably too young to understand at the time. The attention and the drugs and the constant travelling could mask over these things.

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

“There wasn’t a ‘no’ button,” he continues. “I remember one of our first tour managers, we asked him, ‘Can we have our per diems [daily allowance] now?’ He said, ‘No boys, I spent it all on drugs’. It was crazy for me, because I was completely straight. I drank but I didn’t really do anything else. I came from a small town where I wanted to be in Radiohead, then before I knew it I was in a cross between Duran Duran and Happy Mondays.”

Righton recalls the troubled – and eye-wateringly expensive – birth of Klaxons’ 2010 second album Surfing The Void. “We probably spent My Bloody Valentine levels of money on that second album,” he chuckles. “I’m not joking. We went to Milan twice, for six weeks. Got to this amazing studio, the Abbey Road of Milan, old cinema, unbelievable. We all had apartments in Milan for six weeks. Day one, set up the gear. Day two, we go in. ‘Any songs?’ Nothing. Day three, we just go shopping. We then spend the next five weeks going out and shopping in Milan.”

But he isn’t entirely despairing of his Klaxons years. “We had a lot of fun,” he says. “We weren’t a cynical, negative band and we all had personalities.” He shivers at the thought of being in a band again, though. “Bands are brutal. They’re a dog-eat-dog world. I always think it’s really weird that bands stay together because if you’re an actor, you don’t act with the same actors for your whole life.”

When Klaxons broke up after three albums, Righton had perhaps more of a safety net than bandmates Jamie Reynolds and Simon Taylor-Davies. He’d partnered up with Keira Knightley, having randomly sat beside the actor at an Oscars screening party in Soho. “Luckily, I was really, really drunk,” he says. “So I was fearless. I don’t know what I did or said that connected. Maybe she took pity on me.”

As for early dates – dinner in Paris? Night flight over Vegas? “I remember taking her to Thorpe Park,” he says. “I thought that would do it. I was terrified of rollercoasters but I thought I needed to do something that was not the usual. It was a fun time in our lives together, when we could go out until the early morning, come back, have a late lunch, then do it all over again. Now, with two kids, that’s like another lifetime.” And theirs is not exactly an A-lister lifestyle, he says. “I’ve married the least movie star person possible,” James laughs. “You probably know more movie stars than my wife. When she does films, she’s usually got quite a big part, and it means that she has to work really hard and there’s a lot of onus on her.”

So he’s not round Bobby De Niro’s gaff twice a week? “You’re not round Bobby De Niro’s house,” Righton chuckles. “When I go on set, it’s incredible watching her work, because I sometimes forget what she does, but then when I see it, I’m completely blown away. She’s really f***ing good. We’re talking about someone who had a lot of attention at such an early age and managed to survive it. That’s such a strength.”

Righton credits his wife (they married in the south of France in 2013) for seeing him through a post-Klaxons wilderness period where he “hated music” and considered quitting. She encouraged him to play early solo demos, inspired by childhood loves like Todd Rundgren and ELO, to Klaxons producer James Ford, resulting in a 2017 album as Shock Machine. At the same time, Knightley filming The Aftermath in Eastern Europe allowed Righton to indulge his fresh interest in Germany’s Weimar era, gleaned from reading the works of Christopher Isherwood and mainlining Cabaret. With Brexit kicking the nationalist hornets’ nest and Trump’s dark star rising, Righton found modern resonance in “this idea of a party, liberalism and hedonism at a point when things start to turn, and extremism and more fanatical ideas are coming in”.

In Berlin, he took Isherwood tours; in Prague, he rented a cheap analogue studio beneath an apartment block, full of Soviet synths and a “nuclear” hot tub, and spent six weeks constructing the core of The Performer. The record laces hints of Brechtian drama – austere tones, theatrical strings – with Tame Impala’s psychedelia and the sci-fi lounge feel of Arctic Monkeys’ Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino (on which Righton played Wurlitzer). Its retro-modernism extends to drawing political parallels between 1930s Berlin and 2020s Britain on tracks like “See the Monster”, “Devil Is Loose” and “Heavy Heart”.

“I felt really doomed,” he says again, this time after the weeks around the referendum. “There were British politicians who we could see were blatantly and openly lying and it didn’t affect the way people voted. I just find that insane. I’m from an incredibly right-wing town in the middle of England... I go home to my hometown, I’m an alien to my family and friends and everyone I grew up with. When did we become so divided? How did we go to these extremes?”

The monsters and devils of The Performer aren’t just deceit and xenophobia. They represent the climate crisis too. “The human race only ever realises how serious things are when it’s at your door,” Righton argues. “There’s a general underlying level of fear that we all have in society now, a humming thing. Unless you live these puritanical lives, you can’t feel guiltless. That’s why I think there have to be draconian rules that take control of the individual, which is a very fascistic idea, but it’s the only way that we’ll actually do anything. Governments don’t get elected saying, ‘We’re going to lower GDP next year,’ governments get elected on saying, ‘We’re going to increase prosperity and the happiness and the wealth of our nations.’ But that kind of capitalism will only lead to the destruction of our planet.”

If The Performer is politically forthright, it’s also an emotionally frank peek behind the façade of the “celebrity couple” fantasy. In conversation, Righton paints a portrait of a domesticated family life dominated by tag-team parenting, school runs, weekend kids’ parties and all the movie star glamour of a wet Wednesday down Chippenham soft play. He relishes everyday fatherhood, remains “very zen” about tabloid attention and talks of exhaustion, marital point-scoring and rare, snatched trips to restaurants like a grandmaster of Mumsnet. On record, though, things sound somewhat less idyllic. The breezy “Start” daydreams back to more carefree early days of their relationship, and “Lessons In Dreamland Pt. 2” suggests that paradise isn’t entirely trouble free: “The love, the pain…build me up and break me down”.

“It’s more opening up, letting down the guard, letting down your pride, your insecurities,” he explains of the lyric. “You have to break each other down to grow as a partnership. She said, ‘Go and see a therapist’ so I spent a lovely four months chatting with someone outside of my relationship.” What did he learn? “Where the traumas lie…”

And Righton’s lessons in dreamland? “I’ve learnt to control worry, control doubt, control my inner Virgo,” he admits. “I’ve learned to become a better human being – I’m not there, but I’m getting better. I’m less self-consumed, less narcissistic, I’m more selfless, more considerate. I’ve just grown up. It’s a slow growth, because I was in a band for ten years. I was given the card to be able to live an adolescent life forever. You’re celebrated, the more of a child you are.” Luckily, Righton is coming of age again onstage, back where he finally feels he belongs.

The Performer is out now on Deewee

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies