Remembering David Rockefeller: A billionaire banker and philanthropist

‘He was the epitome of courtesy and discretion, exquisitely mannered, never flustered, a patrician to his fingertips’

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, some people believed that David Rockefeller secretly ran the world. Indeed, if you were a conspiracy theorist of a leftwing bent, the case was all but irresistible. He was after all chairman of the Chase Manhattan Bank, then at its zenith. He was founder and chairman of the Trilateral Commission, bringing together the political and financial elites of the US, Japan and Europe. Most important, he was a Rockefeller.

If the rich are different from other people, the Rockefellers in that era were somehow different from the even richest Americans. David was the youngest of the six children of John D Rockefeller Jr, philanthropist son of John D Sr, founder of the Standard Oil Trust, America’s first billionaire and primus inter pares of the 19th century robber barons.

One of David’s brothers was Nelson, governor of the state of New York and US vice-President between 1974 and 1977. The Rockefellers were living symbols of a seemingly eternal East Coast establishment, the closest thing – with the possible exception of the Kennedys – to an American royal family.

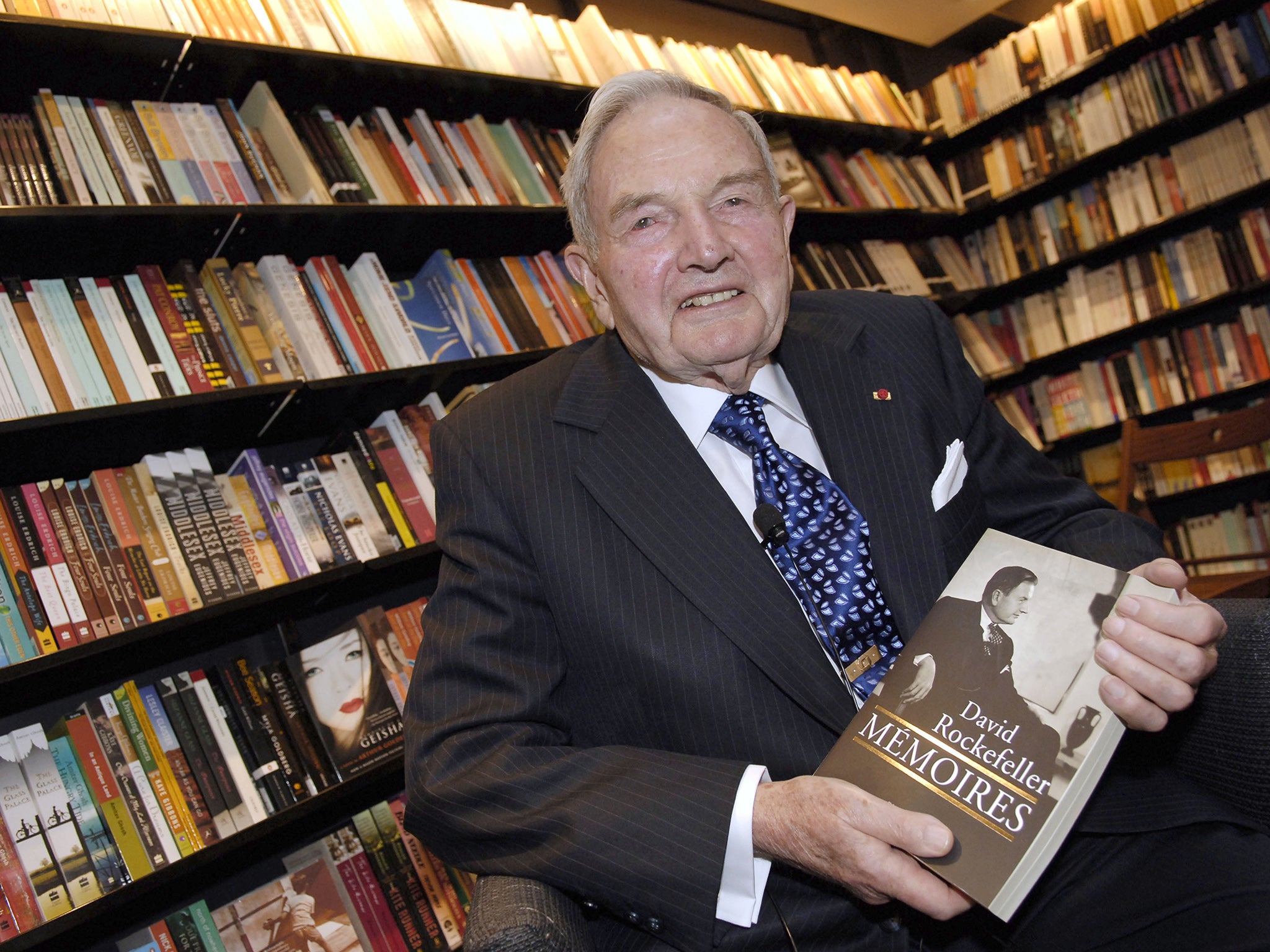

From earliest childhood, the young David was aware that he had been born into no ordinary household. “Father .... set the standard for being a Rockefeller very high,” he wrote in Memoirs, an autobiography published in 2002. “Our every achievement was taken for granted, and perfection was the norm.”

He grew up on West 54th Street, in what was then the largest private home in New York, boasting nine floors with its own squash court and infirmary. Weekends were spent at the family’s 3,500-acre estate north of the city where John D Sr played card games and golf with David, his favourite grandchild.

The siblings did ordinary American things, but with a distinct Rockefeller twist. They would roller-skate up Fifth Avenue to school – but with a limousine slowly following them, to collect them if they tired. Each Thanksgiving, the young David would deliver food parcels to the poor – but a liveried chauffeur was beside him to help carry them. Every summer the family took a train to Maine. The train however consisted of private Pullman cars, with extra carriages to carry the family horses.

Less gregarious than Nelson, fascinated by travel and an avid collector of insects, David was a rather solitary, but happy child. A love of art was in his blood. In 1929, when he was 14, his parents founded New York’s Museum of Modern Art. David was associated with the museum for six decades, and in 2005 he pledged $100m (£80.9m) to MoMA, its largest-ever single donation. Gauguins and Picassos adorned the walls of his office on the 56th floor of the Rockefeller Centre.

But by Rockefeller standards he got his hands dirty. Not only was he the first of the clan to write an autobiography; he was also the first since his grandfather to earn a company salary – from Chase, the family bank which David entered in 1946 after service in the Second World War and would lead for two decades, from 1961 to 1981.

As a commercial banker, he might have been outperformed by Walter Wriston, who turned Chase’s great rival, Citibank, into America’s largest and most innovative financial institution. But as a pillar of the US establishment, no-one came close. Not only did David Rockefeller have access to anyone on earth who mattered; he seemed to know them all personally as well.

His Rolodex, an immense store of reputedly some 100,000 names that he kept in a special room next to his office, became legend. Not only did he run the bank. For decades he was the pre-eminent spokesman for US business. He was a long-serving chairman of the venerable Council on Foreign Relations, and in 1973 co-founded the Trilateral Commission, grouping the great and good of the Western world.

Both Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter unavailingly offered him the job of Secretary of the Treasury, and Carter also approached him to become chairman of the Federal Reserve. Small wonder the conspiracy theories – fanned, it must be said, by Rockefeller’s readiness to hobnob not just with presidents, prime ministers and princes, but dictators as well.

It could be argued that as chairman of a global bank, he could not afford to be as fastidious in his business relationships as he was in his private life. David Rockefeller claimed that Nelson Mandela was the man who he admired most. But others never forgave him for how he, along with his old friend Henry Kissinger, engineered the entry of the Shah of Iran – much reviled tyrant but major client of Chase Manhattan – into the US after the 1979 Islamic revolution.

Always however, he was the epitome of courtesy and discretion, exquisitely mannered, never flustered, a patrician to his fingertips. “Only once in my life did I almost become uncivil,” he once observed – a claim that would beggar belief for any other member of the human race, but quite believable to anyone who met David Rockefeller.

In some ways he could be defined in comparison to Nelson, the elder brother whom he idolised, then fell out with. David’s style was reserved and silky smooth. Nelson was a blustering, vanity-laden force of nature. David was an adoring husband for over 50 years; his brother was a philanderer who brazenly divorced his first wife, regardless of the political consequences – then offended David by demanding he buy Nelson’s interest in a Brazilian ranch, to fill his campaign coffers.

Sibling tensions only grew when Nelson attempted to set himself up as head of the family after his embittered return from his two-year stint as Vice President, which ended when Gerald Ford dropped him from the 1976 Republican ticket, to appease the party’s right wing.

Earlier in the year, a lawyer for President Donald Trump compared the questions about his wealth and potential conflicts of interest to Nelson – with Trump perhaps one of the only other business to now wield the same clout as the Rockefellers.

Nelson “knew what he wanted, and if you got in the way, he was not particularly gentle in pushing you aside,” David noted years later. And yet, “he taught me to loosen up, to enjoy, to take pleasure in the ‘great game’ of life. If my brother sometimes played that game with too much abandon, he helped me play it more ardently and with greater zest.”

Just before his death, David’s net wealth was estimated at $3.3bn (£2.6bn), yet David to the end described himself as a “Rockefeller Republican,” a social moderate with a sense of “noblesse oblige”, who believed that the rich had a duty to help the less well off (a philosophy, like ‘one nation’ Toryism in Britain, that has virtually disappeared in today’s Republican party.)

Had he been a member of the House of Commons though, David Rockefeller would have made a perfect knight of the shires. There was another touch of well-heeled English eccentricity about him too. In a parallel existence as an entomologist, Rockefeller amassed a collection of beetles even more voluminous than his Rolodex, containing 150,000 specimens and, representing about 2,000 species (two of which are named after him).

Almost inevitably, his own six children, coming of age in the turbulent and questioning 1960s, in one way and another, at varying times, rejected the establishment that David represented. But the rifts were healed as they rallied around their father, patriarch of the dynasty, after the loss of his beloved Peggy in 1996. “I can only say I have had a wonderful life,” David Rockfeller said, as he entered his 90s. The less fortunate could hardly disagree.

David Rockefeller, US banker and philanthropist. Born New York City, 12 June 1915. Married 1940 Margaret ‘Peggy’ McGrath (died 1996, two sons, four daughters). Chairman, Chase Manhattan Bank 1969-1981. Chairman, Council of Foreign Relations 1970-1985. Co-founder of the Trilateral Commission, 1973. Trustee and later chairman of the Museum of Modern Art, New York City. Died 20 March 2017, aged 101

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies