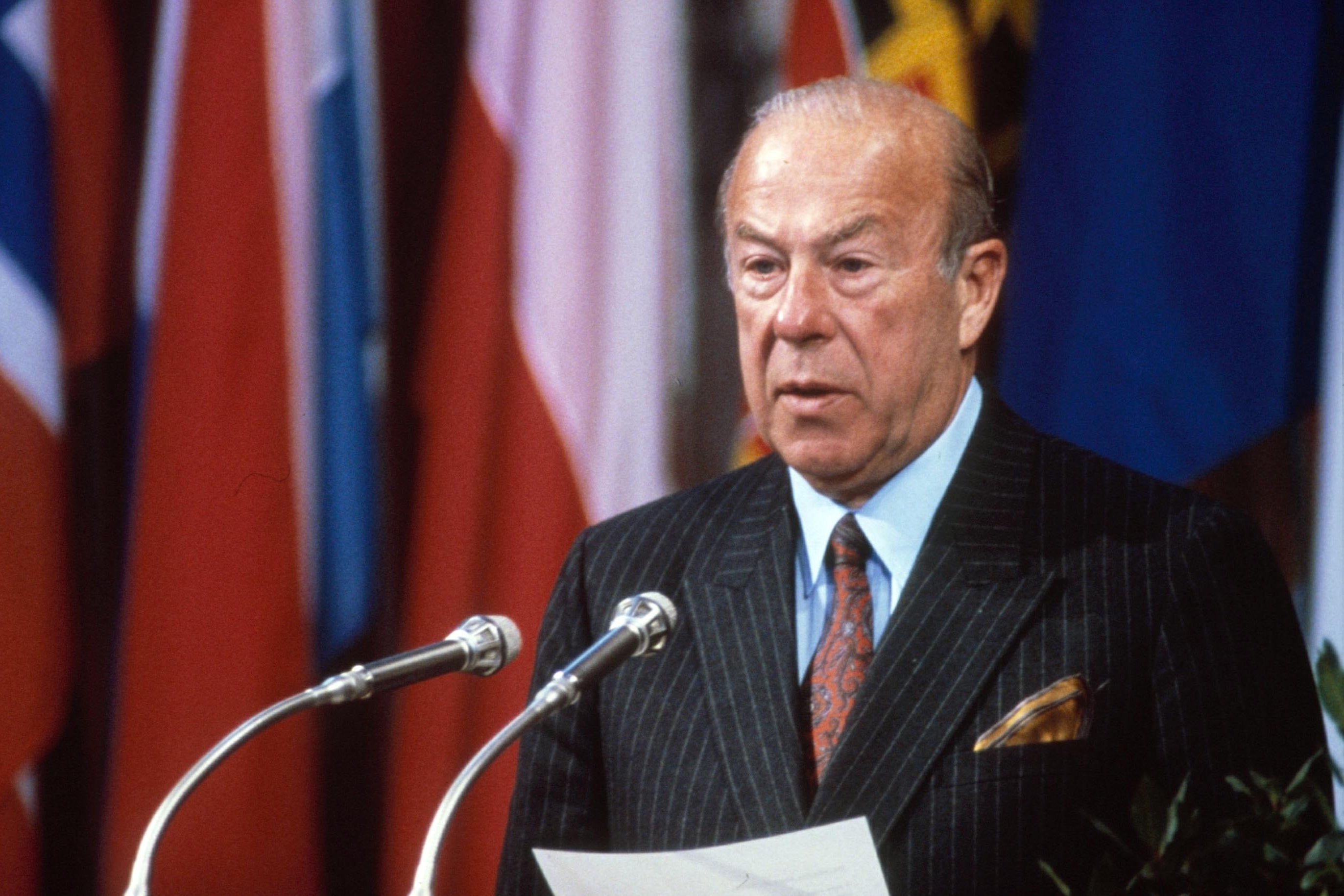

George Shultz: US secretary of state who helped to end the Cold War

He owned the safest pair of diplomatic hands in the business at a time when pragmatism was needed most

By his own admission, George Shultz was no great conceptual or strategic thinker, neither as a labour economist, a businessman nor in the senior cabinet posts he held under Nixon and Reagan. He was even less of an orator; indeed, a Shultz speech, delivered in that patented low, measured plod could be a veritable ordeal to sit through.

But as US secretary of state, the office he filled between 1982 and 1989 at the peak of his career, he was uniquely suited to the times. His style was usually described as “incremental” – in other words, moving warily and step by step on the foundation of a few core convictions – and at a stage of the Cold War when most of the movement was coming from the other superpower, this pragmatic approach was perfect. He did not trust the Soviet Union, but when it was apparent that Mikhail Gorbachev was sincere in his desire for change, Shultz was prepared to engage.

However, he would never be rushed; his physical presence personified steadiness, thoroughness and careful judgement. By common consent, he owned the safest pair of diplomatic hands in the business. None other than Henry Kissinger remarked of him, “If I could choose one American to whom I would entrust the nation’s fate, it would be George Shultz.”

In retrospect, it was almost inevitable that this only child of a New York businessman and investment adviser would enter public service. Raised in a wealthy New Jersey suburb, Shultz took a good economics degree at Princeton in 1942 and then served in the US marines until the end of the war. In 1949 he obtained a doctorate in industrial economics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he first elaborated his argument that wage negotiations were usually best left to the parties directly involved, and that outside mediators and arbitrators, however well intentioned, were generally more encumbrance than help. His reputation was quickly established. There followed a job on the faculty at MIT, a stint on Eisenhower’s Council of Economic Advisers, 10 years as a professor of industrial relations at the University of Chicago, and a spell as a resident scholar at Stanford University in California.

Throughout these years, from 1950 to 1968, Shultz was constantly in demand from both Republican and Democrat administrations to serve on committees and taskforces dealing with labour issues. Both unions and management came to respect him greatly, and it was both hugely popular, and virtually inevitable that in 1969 he would become secretary of labour for the new president, Richard Nixon.

Though he clashed bitterly with organised labour over increases in the minimum wage (which Shultz believed would slow the creation of jobs for marginal workers), his tenure was broadly a success. Within two years he had been promoted to head the newly created Office of Management and Budget, and in May 1972 he became treasury secretary. By the time he resigned in March 1974, unhappy at the imposition of a 60-day price freeze and increasingly disturbed by Watergate scandal, Shultz was probably the third most powerful man in US government after Kissinger and Nixon himself.

But five and a half years in Washington had been enough. Shultz returned to California and the Bechtel group of San Francisco, one of the world’s largest (and perhaps its most secretive) civil engineering and construction concerns. Though he would become president of the company, old academic habits were strong enough for him to find time to teach several business classes at Stanford.

Many thought Shultz would be Ronald Reagan’s first secretary of state after the 1980 election, but the job went to Alexander Haig, the former Nato supreme commander whose hawkish views were more appealing to the influential Republican right. But in June 1982 Haig resigned – and in July, after the Senate voted 97-0 to confirm him, George Shultz was sworn in as his successor.

The changed atmosphere in government was immediately evident. Thoughtful and unflappable where Haig had been temperamental and impulsive, the new secretary quickly won the confidence of both his staff and his counterparts abroad. His first success was to defuse a nasty dispute with the Europeans over a proposed pipeline to import gas from Siberia. At the same time, Shultz and Reagan launched a new Middle East initiative offering Israel security guarantees in return for territory.

But what did most to shape Shultz’ attitude to the region was the bombing of the US barracks in Beirut costing the lives of more than 200 American soldiers – by his own account the worst moment of his career in government. Thereafter his loathing of terrorism was implacable. It was one (though not the only) reason for his outrage at the Iran-Contra affair, in which White House officials secretly supplied arms to Iran in return for the release of American hostages in Beirut, and channelled the proceeds into secret aid for the rebel Contras in Nicaragua. Shultz was widely believed too to have been loudest in urging Reagan to bomb Libya in April 1986 after Colonle Ghaddafi’s agents had allegedly planted a bomb in a Berlin nightclub, killing two American servicemen.

But his reputation rests on his dealings with the Soviet Union. Early on, nothing changed – indeed relations if anything worsened with the downing of flight KAL 007 in September 1983 in the Soviet Far East, and the deployment by Nato of new intermediate-range nuclear weapons (INF) in Europe. But with the arrival of Gorbachev and his Georgian-born foreign minister Eduard Shevardnadze, the outlook was transformed.

Quickly Shultz struck up a working relationship – later to blossom into genuine personal friendship – with Shevardnadze. The pace of superpower meetings quickened: the “getting to know you” summit in Geneva 1985, followed by the dramatic encounter at Reykjavik the next year. Shultz, not his great rival, Caspar Weinberger at the Pentagon, accompanied Reagan to a meeting that came within an ace of virtually abolishing all nuclear weapons. The sticking point was the president’s insistence on retaining his “Star Wars” programme. Afterwards, Shultz appeared before the press, visibly close to tears at what seemed a colossal failure. In reality, the Iceland summit paved the way for what would follow: a treaty eliminating INF in its entirety at the Washington summit of December 1987, and further arms control agreements in the Moscow meeting the following May. In all these events the role of Shultz was quiet but crucial.

By the standards of the day, and certainly in comparison with the hawkish Weinberger, he was a moderate – a visceral anti-Communist who was nonetheless acutely aware of the delicacy and difficulty of the reforms that Gorbachev was attempting, and who believed that both sides had to make concessions to obtain a deal.

In public, Shultz came across as a placid and sometimes almost lugubrious figure. The key was his extraordinarily close and mutually trusting private relationship with Reagan. In contrast to Haig, he was instantly an “insider”, a secretary of state of an influence and authority which in the post-Kissinger period only James Baker has rivalled. Hence perhaps his particular fury at the Iran-Contra affair. Shultz was not involved in the shenanigans, orchestrated by the national security adviser John Poindexter and his aide Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North; indeed he implored Reagan, without success, to veto the operations.

His failure to do so however only heightened his embarrassment: if he was not a crook, he was a soft touch – a secretary of state whom White House operatives could ignore in the making of foreign policy. It took an impassioned and devastatingly frank appearance before the congressional committee investigating Iran-Contra, revealing a Shultz few had suspected, to restore his reputation. The INF treaty completed the rehabilitation.

After leaving Washington, Shultz returned to live in California. But Shultz’ advice was constantly sought out by Republicans aspiring to high office. Though he had little to do with the Bush administration, he was at almost 80 a foreign policy adviser to George W Bush in the 2000 presidential campaign – an emblem of a seriousness and constancy which many felt had vanished from America’s conduct of foreign affairs. Shultz refused to endorse Donald Trump for the presidency in 2016 and he was a strong advocate of policies to address the climate crisis.

He married Helena O’Brien, an army nurse, in 1946 and they had five children. After her death, in 1995, he married Charlotte Mailliard, San Francisco’s chief of protocol, in 1997. He is survived by his wife, five children, 11 grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.

George Shultz, US secretary of state, born 13 December 1920, died 6 February 2021

Rupert Cornwell died in 2017

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.