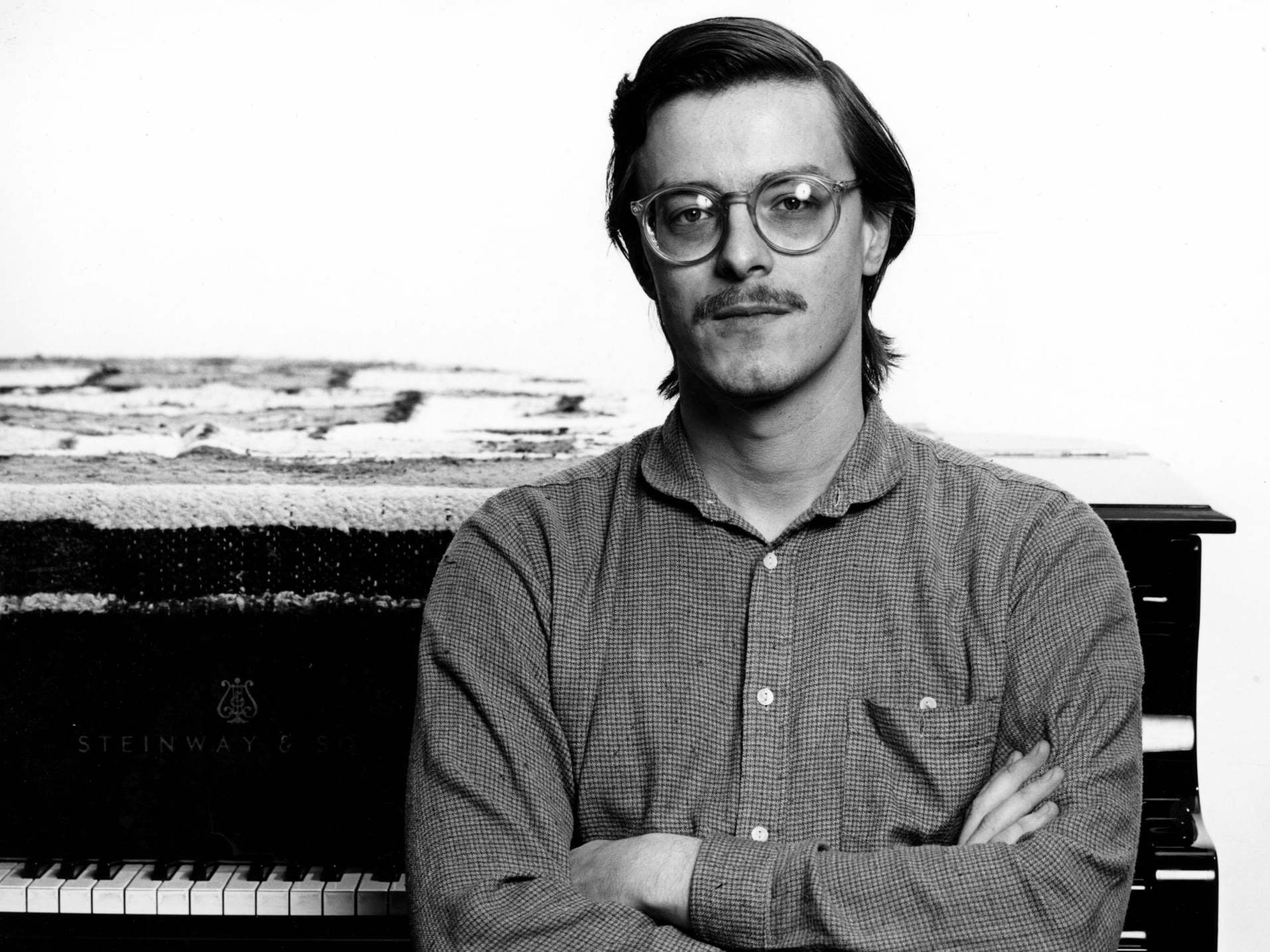

Peter Serkin: Pianist who defied family traditionalism with a contemporary outlook

Noted for his performances of Schoenberg and Messiaen, he acquired a reputation as a concert-hall rebel

A piano prodigy who made his professional debut at age 12, Peter Serkin seemed destined from childhood to carry on the legacy of his father, Rudolf Serkin, one of the 20th century’s most revered pianists.

But while the elder Serkin was celebrated for breathing new life into Beethoven and other old masters, his son became known for championing the work of 20th-century composers such as Oliver Knussen, Toru Takemitsu, Stefan Wolpe and his childhood friend Peter Lieberson, even as he worked to reveal rich new textures in the classical repertoire so cherished by his father.

Serkin, who has died of pancreatic cancer aged 72, played everything from Bach to Berio and Mozart to Messiaen, sometimes using a 19th-century fortepiano to perform period works. He also acquired a reputation as something of a concert-hall rebel, performing in a dashiki and love beads in the early 1970s before trading his countercultural attire for three-piece pinstripe suits, settling into a role as one of his generation’s preeminent performers.

He regularly commissioned works from contemporary composers – a stark departure from the traditionalism of his father and maternal grandfather, the conductor and violinist Adolf Busch. The two co-founded the Marlboro school along with Adolf's brother Herman. Rudolf and Adolf were among those who started a chamber festival in Vermont, US, a classical-music incubator that shaped legions of young musicians – including Serkin.

Serkin admired Frank Zappa, John McLaughlin, the Grateful Dead, John Coltrane and Sun Ra in addition to classical works. Among the latter, his favourites included Arnold Schoenberg’s keyboard compositions, which he recorded in full, and Olivier Messiaen’s eight-movement Quartet for the End of Time, which he performed roughly 150 times with his chamber group the Tashi Quartet.

Serkin recorded numerous albums for RCA Red Seal Records, performed solo recitals around the world, accompanied leading orchestras and chamber groups, and taught at the Juilliard School, Tanglewood, Curtis Institute of Music and Bard College Conservatory of Music. He eschewed publicity and once declared that he’d “rather play 20 concerts before 3,000 people than give one interview”.

Early on it seemed that his music career might collapse under the weight of professional pressures and family expectations. Beginning in the late 1960s, when he was in his mid-twenties and primarily focused on standard repertory, Serkin abandoned the piano to embark on soul-searching journeys to Mexico and India. He became interested in religion, immersing himself in the Sufi, Buddhist and Hindu faiths, but recalled ending his Mexico trip after hearing a radio broadcast of Bach’s Fifth Brandenburg Concerto wafting on the breeze.

It was the kind of loose, emotionally intense performance that had long eluded him. He returned from his travels with a more relaxed approach to music, even as he maintained an academic rigour that he learned from his father, studying composers’ letters and examining first editions of their scores.

“The idea so many musicians have – that you have to act out the music for the audience, to supply it as a solidified object – is death,” he said. “Music is change, it’s process, not a static thing. And if you want to be part of that process you have to continue to grow.”

The fifth of seven children, Peter Adolf Serkin was born in Manhattan, New York, in 1947. His middle name was an homage to his grandfather Busch, with whom the Bohemian-born Rudolf Serkin began performing as a teenager in Berlin (both men immigrated to the United States after the outbreak of the Second World War).

His mother Irene was also a musician, who played piano, violin and viola. She was credited with helping to keep the Marlboro festival afloat after Adolf’s death in 1952, and it was there that Serkin made his formal debut, performing a Haydn concerto under the conductor Alexander Schneider.

Serkin studied at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, taking lessons from Polish-born virtuoso Mieczyslaw Horszowski, American pianist Lee Luvisi and his own father before graduating in 1964. Two years later, his recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations earned him a Grammy award for most promising new classical recording artist. In 1967, at the age of 19, he made his grand-scale New York debut, performing Beethoven’s notoriously difficult Diabelli Variations at Philharmonic Hall.

He angered some members of the music establishment with his modern attire and unconventional music selections before gaining widespread recognition as a bridge between old and new musical traditions. Through the Tashi Quartet, formed in 1973 and named for the Tibetan word for good fortune, he also helped to bring younger audiences to the repertoire.

Serkin’s recitals often featured a mix of old and new, surveying hundreds of years of musical tradition in less than 90 minutes. But he dismissed suggestions that he was trying to update old works, saying he aimed “to project the up-to-date-ness that already exists in the music”.

Composers like Bach and Beethoven “were so infamous in their own day for being outlandish, outrageous”, he continued. “That’s expressed in the music in a very healthy way. Like crazy sanity. Wild discipline. I try to relate to these pieces now as part of our own lives, in a very personal way, with feeling and emotion, but never with a concern that I want to show the listener how deep my feelings are.”

He was married twice, to Wendy Spinner and Regina Touhey, and is survived by five children.

Peter Serkin, musician, born 24 July 1947, died 1 February 2020

© Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies