The Weasel: Bitter memories

What better than an aperitif to introduce this magazine's summer banquet? But before anyone gets excited, I feel obliged to point out that you probably won't like it. Though eagerly consumed in a few spots around the world, we don't care for this potent Italian bracer in the UK. Dark brown in colour, somewhat similar in appearance to the liquid that leaches from ancient vegetables forgotten in the larder, it has an aggressive bitterness that does not chime with the British palate. Mostly, it is regarded here as a kill-or-cure hangover remedy, though there are a few enthusiasts who take it onboard for pleasure and, just possibly, as a hangover cure as well. One is Fergus Henderson, the genial chef-patron of St John restaurant.

"Uplifting, very uplifting," replied Fergus, when I asked for his opinion of this acerbic grog. "I find it very efficacious." Such is his zeal for the stuff that Fergus once visited the production plant in Milan. When I showed interest, he expressed willingness to pay a return visit. In consequence, a party of intrepid topers, including Fergus, the Weasel and Fergus's father, the architect Brian Henderson, made the trek last week to the imposing 1908 factory on via Resegone that produces 15 million litres per year of Fernet-Branca.

A cocktail advocated by Mr Henderson Snr that contains the astringent potion appears in Fergus's celebrated cookbook Nose to Tail Eating. The formula in the book for the "Dr Henderson" (an honorific bestowed by a Parisian bartender, who mixed up both the drink and the name of its consumer) consists of two parts Fernet-Branca to one part crème de menthe, though Mr Henderson Snr advocates a ratio of 7:1. "Mix together with ice and drink," wrote Fergus. "Do not be put off by the colour." In his sequel Beyond Nose to Tail, Fergus included a recipe for Dr Henderson ice-cream, but this did not impress his father. "I was none too pleased," said Mr Henderson Snr. "It devalued the currency."

"What's the ice-cream like?"

"Not to my taste."

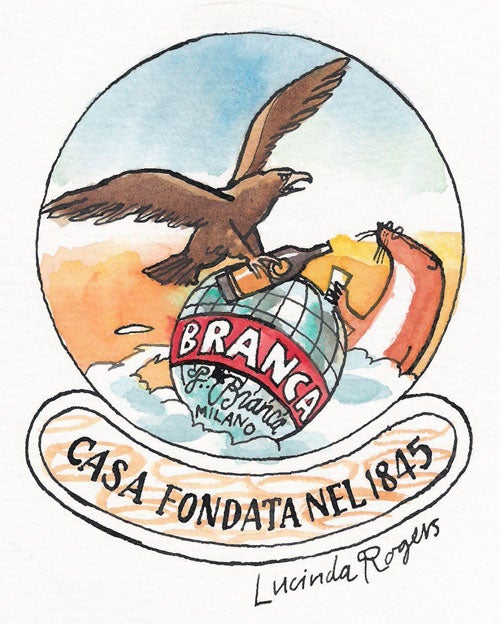

The distinctive label surmounted by an eagle that bears some similarity to The Independent's eagle (except that it carries a bottle rather than a newspaper) declares that Fernet-Branca only contains "ingredienti naturali ed esorici" (natural and exotic ingredients). The truth of this statement was borne out by a display of 40-odd materials that might be found in a wizard's lair. Unsurprisingly, many came from the bitter end of the taste spectrum. They included such rarities as dried Chinese rhubarb (large, brown chunks of dried rhizome quite unlike the familiar stalk), white agaric (lumps of chalky fungus), cinchona (a source of quinine), aloes (a spice synonymous with bitterness), zedoary (described as "similar to ginger but with a bitter aftertaste") and myrrh, which is crystallised, aromatic sap. But perhaps the most surprising ingredient is saffron. Fernet-Branca is a leading buyer of the world's most expensive spice. Every year, "a few tons" are incorporated in the drink, where it is mainly detectable as a yellow smear left when a glass is emptied.

Formulated by Maria Branca in 1845 (the "Fernet" bit means "body cleanser"), it was initially intended to treat female ailments. Comely consumers delicately sip the stuff in early advertisements (Fergus prefers the down-in-one approach). As a medicine, albeit one that was over 40 per cent alcohol by volume, Fernet-Branca escaped Prohibition in the US. The company is still family owned. Once every six months, Count Nicolo Branca visits the factory and mixes up a batch from a secret formula. "These days he uses a computer," said export manager Enzo Vogliol. "The ingredients are no secret. The secret lies in the quantities." When extracts have been made from the recondite ingredients, they are combined with alcohol and left to mature in acacia barrels for a year.

Today, the Argentines consume so much (15 million litres per year, almost all drunk with Coca-Cola) that they have their own factory in Buenos Aires. In Scandinavia, it has become fashionable to consume Fernet-Branca as a shot accompanying a glass of beer. Two bars in Trondheim sell over 3,000 bottles a year, which is around one-tenth of total UK consumption. "You don't have a taste for bitter things," shrugged Mr Voglioni. Viewing the 3-litre bottle on the table of a Milanese restaurant with unalloyed delight, Fergus did his best to disprove this view of our wimpish taste: "A spot more would go down rather well."

I liked the drink in Milan, though it does deliver a shock to the system akin to a biff on the beezer. Back home, I found myself less keen, though this might have been due to my companions. "Ah can't sweak," grimaced Mrs W after taking a mouthful onboard. When life returned to her larynx, she added: "I can feel it going down. You know it's a complex drink. You can taste all sorts of things going off in your head."

"Want any more?"

"You're on your own with that."

My friend Matthew, though by means averse to most alcoholic beverages, shared her antipathy. "Collis Brown!" he gasped. "By the hell, it's horrid ... Could grow on you though." But I noticed that the level in his glass did not decline after his initial sip. The 7:1 Dr Henderson proved far more acceptable. "I can manage two gulps of that," said Mrs W. For Fernet-Branca companionship, I may need to return to Milan – or possibly St John.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies