Honesty box hotels: You decide how much you pay

Five hotels in Paris now allow guests to pay only what they think their stay was worth. It seems fraught with financial risk, but the honesty policy has its benefit. Gillian Orr reports

Anyone who has ever bowed their head and scurried past the box marked “suggested donation” without reaching into their pocket on their way into a museum or art gallery – I’m certainly guilty – might well have their doubts about a new business enterprise in Paris.

This week, five hotels in the city’s 9th and 11th arrondissements launched a scheme in some of their rooms that allows guests to pay whatever they feel like at the end of their stay. No flat rates, no extra for a view of the Sacré-Coeur. Just however many euros visitors are happy to part with.

“It’s a fair-price operation, one of confidence in the client,” says Aldric Duval, the head of the Tour d’Auvergne hotel, one of the participating venues, and the man who came up with the idea.

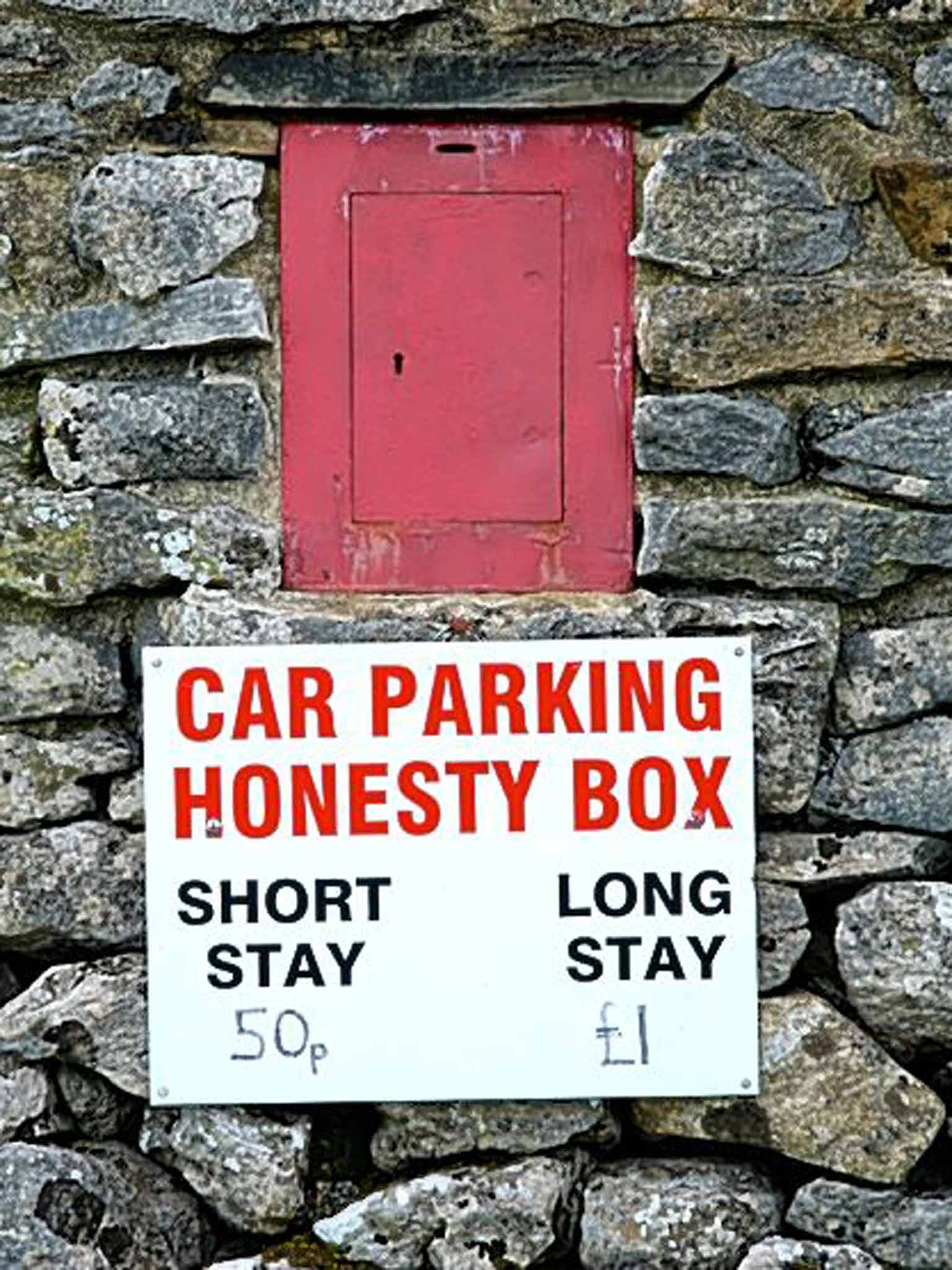

One might accuse Duval of naïveté. After all, this is a world in which WH Smith had to uninstall honesty boxes for its newspapers earlier this year after staff found that customers could not be trusted to give the right change, preferring instead to “pay” with chewing gum and foreign coins. And that was only for items costing a quid or two. Honesty boxes may thrive at churches and local farms, but can they succeed in big business? And how would a hotel fare with a similar strategy?

“Actually, people have an altruistic motive and will pay a positive amount because they feel that they should pay the seller and they care about them,” says Vincent Mak, a lecturer in marketing at the University of Cambridge and a co-author of the study “Pay What You Want” as a Profitable Pricing Strategy.

“But I have the suspicion that these hotels will suffer losses. People will pay something, but these hotels will not be able to earn as much as if they had simply charged a going rate for the market.”

Indeed, Duval tells me that his very first customer paid €140 (£111) for a night. The average cost of a room in the area, he says, is between €150 (£118) and €200 (£158). He sounds pleased but I can’t help but wonder why he doesn’t just charge the full whack.

But such offers have other rewards. Specifically, had anyone even heard of the Tour d’Auvergne before it offered this unusual deal? It is a tactic that has worked for restaurants around the world. “If this campaign is carried out with sufficient momentum, creates a lot of press and activity on social media so that people find out about it, and indeed motivate each other to actually pay well, then it could succeed,” observes Professor Mak.

The added publicity that surrounded Radiohead’s move to ask fans to pay what they felt like for their 2007 album, In Rainbows, saw downloads soar. And 38 per cent of customers actually coughed up, which was enough for one member of the band to assure the public that, in digital terms, it was their most successful record yet.

Get a free fractional share worth up to £100.

Capital at risk.

Terms and conditions apply.

ADVERTISEMENT

Get a free fractional share worth up to £100.

Capital at risk.

Terms and conditions apply.

ADVERTISEMENT

Meanwhile, at the Edinburgh Festival this year, the comedian Lewis Schaffer will give audience members the option to pre-purchase tickets for £5, or to give what they feel at the end of the show.

“I don’t make much money at the Edinburgh Festival doing pay-what-you-want shows. I do it that way so I can guarantee that more people see me,” says Schaffer. “But I’m using the same business model as last year. And that didn’t work. I don’t know why I’m doing it again.” It may explain why he has called his show Success Is Not an Option.

Interestingly, in Freakonomics, the most popular pop-economics book in history, a chap called Paul Feldman sets up a bagel business in an office based on the honour system. He discovers that people are more likely to pay better when the weather is nice. He also believes that higher-paid executives cheat more than workers lower on the corporate ladder.

By that logic, Duval’s hotel should at least do well over the summer. But he might be hoping that the more well-heeled tourists go elsewhere to lay their head when visiting the City of Light.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks