The Weasel: The ghost writer

The most evocative writer's home in the UK is owned by the city of Paris. "No house ever said so much about its owner," declares Graham Robb in his masterly biography of Victor Hugo. "Hauteville House gives one the distinct impression of being swallowed alive by Hugo." During our recent visit to Guernsey, Mrs W and I puffed up the steep street in St Peter Port to the four-storey dwelling of this titan of letters for 14 years from 1855. After we rang on the bell, a doorkeeper brusquely inquired, "French or English?" When this had been sorted out, we had to give our names and were told to present ourselves half an hour later for a tour in English. It was all a bit bureaucratic considering the former owner's disdain for authority. During the wait, we explored the garden, which, like the house itself, is immaculately maintained by its Parisian curators.

In exile from the regime of Napoleon III, Hugo first took up residence in Jersey. His subsequent expulsion from the island ensured a warm welcome in Guernsey. Graham Robb underestimates the "tradition of mild antagonism" between these two dots of granite in the English Channel. Hugo acquired Hauteville House relatively cheaply because, Robb informs us, "Its previous resident, a vicar, had been chased out by a ghost." By contrast, Hugo relished supernatural company and enjoyed bedtime chats with the ghost and a few more spectral chums. Apparently, the supernatural residents also practised a form of Morse Code but we heard no tapping. Robb remarks that, following Hugo's idiosyncratic decoration of the house, the ghosts probably felt more at home there than human beings.

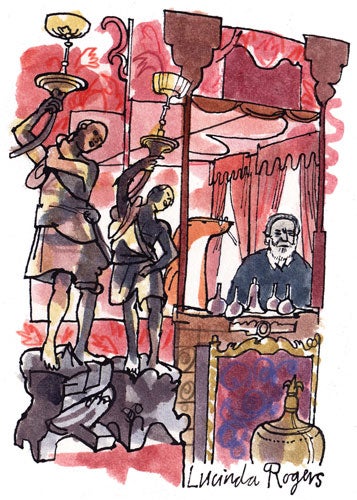

"You're not allowed to sit anywhere and try to avoid using the flash," said our guide Cédric Bail, before adding: "The house is a bit mysterious, very strange and peculiar." After this build-up, the billiard room proved a slight let-down. "A less interesting room," admitted M Bail. " 'ugo did not play billiards." But the darkly gleaming dining room – it is lined with wood from 70 carved seaman's chests purchased by Hugo and illuminated by tiny portholes made from "bull's eyes" cut from wine-bottle bottoms – lived up to expectations. So did a passageway lined with crockery (including the ceiling) and an exotic smoking room decorated with Gobelins tapestries, casually cut up by Hugo and nailed to the walls. Mysteriously, we were not shown the kitchen ("It's nothing special," said our guide), though we occasionally caught a fragrant whiff of cooking, possibly navarin d'agneau, like a fleeting ghost.

The surprises continued on upper stories. Bizarrely, a large, gloomy room contained a long judicial table with magistrates' chairs and a four-poster bed that was never used. A carved legend declares: "Nox Mors Lux" (Night Death Light). "This room is a symbolic place," explained M Bail. "We must pass through judgement and death to reach light and freedom." These are found on the airy top floor where Hugo built a "Crystal Room" to contain his workroom and tiny bedroom. He was scarcely lonely in the latter. Aside from supernatural company, the writer was accompanied by a series of servant girls. Sometimes, the comings and goings were reminiscent of a Feydeau farce. Hugo recorded one visitor "leaving by one door while someone enters by another", though his biographer conjectures that this might be "one of Hugo's oblique allusions to complicated sexual acts".

A line of windows gave Hugo a view of Sark, Jersey and (on clear days) the outline of Brittany. The English Channel, flecked with white horses at the time of our visit, inspired his Guernsey novel The Toilers of the Sea, which culminates in 10 pages describing the hero's fight with an octopus: "Gilliatt... had the impression that he was being swallowed by a host of mouths that were too small for the task." Our guide gave a particularly Gallic summary of our symbolic journey, "We have gone from death to life, from dark to light, from ignorance to knowledge", before departing for lunch with the ghosts.

It is instructive to compare the scrupulous care that the French lavish on their national treasure with the British commemoration of Guernsey's other literary star. Though it is the 150th anniversary of his birth, there was no trace of H W Fowler (1858-1933). He compiled both the Concise and the Pocket Oxford Dictionary, but is best known for his Dictionary of Modern English Usage, an unexpectedly amusing dictionary that has guided readers through the pitfalls of the language for the past 85 years. Fowler wrote this work on Guernsey after moving there in 1903. For much of his time on the island, he lived in a cottage at Rocquaine Bay, near the home of his brother, who was a tomato grower.

Published in 1923, his masterpiece contains several entries that suggest its place of composition. They include "codlin[g]. Spell with the g", "island, isle. The two are etymologically unconnected, the first being native... the second being Latin", "littoral... in ordinary contexts it should never be preferred to coast", "sardine. Pronounce sar'din" and (possibly a tribute to V. Hugo) "octopus. Pl. –uses. The Greek or Latin pl., rarely used, is –podes not –pi".

We shared Fowler's fondness for Rocquaine Bay, where he startled locals by jogging. His biographer Jenny McMorris notes that children found "running for pleasure very odd, as their parents only ran in emergencies". We ate crab sandwiches on the beach where he took his daily swim, but were'nt able to visit his cottage. "Unfortunately," McMorris explains, "[it was] destroyed years ago."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies