Here is the perfect illustration of how a picture can change a book for you

Plus: TV's obsession with Gershwin and New York gives me the blues and there's been a nervous breakdown at Charlie's Chocolate factory

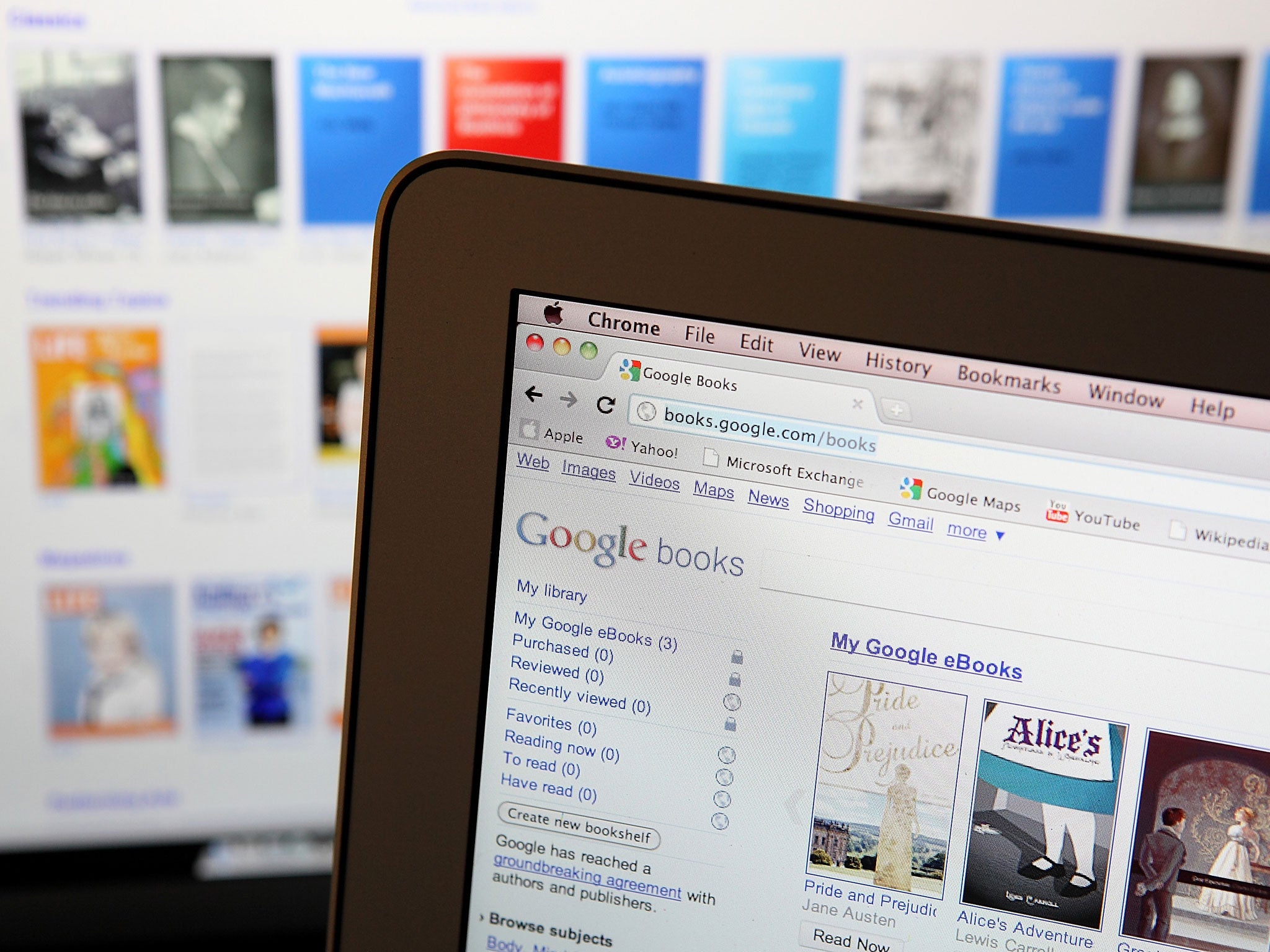

The age of the unillustrated book is dying. I know this sounds as if it's the wrong way round. After all, it's the illustrated book that would seem to be a thing of the past, unless you're talking about children's literature. And the fact that you almost certainly would be talking about children's literature is evidence in itself of a shift in fashion, from a time when quite a lot of popular fiction would come with illustrations to a time when it would be a remarkable breach of publishing protocol. Imagine opening Dan Brown's Inferno and finding a pencil sketch of his hero, or an interleaved drawing of Istanbul.

The Folio Society's editions often still contain illustrations but the fact that they do is what makes me hesitate to buy them, despite the seductive quality of their bindings and paper. Because, as any sensitive reader knows, a bad illustration – or even just one that doesn't match your own inner eye – can kill the imagination stone dead. And yet books have never been more illustrated, more haunted by the images of the things they describe.

I think I've sensed this for a while but it was Michael Wood's review of Julian Barnes's novel Levels of Life in the London Review of Books that really brought it home to me. Discussing the second part of Barnes's book – which describes a love affair between a Victorian adventurer called Fred Burnaby and Sarah Bernhardt – Wood writes, as an aside "if you google him you will see a fine picture of him by Tissot".

And – if you happen to be reading this on an iPad or a laptop – you can almost certainly do the same, with the same insouciant rapidity implied by Wood's dashed interpolation. I did it myself while reading Levels of Life, provoked initially by the desire to check whether Burnaby was as real as Bernhardt. But once I had, Tissot's painting of Burnaby, lounging on a sofa with a cigarette canted in his hand and the scarlet stripe of his uniform trousers stroking the length of his legs, was irretrievably part of the experience of reading Barnes's book.

Fair enough, you might say. Barnes has often referred to real objects and real people in his fictions, and we get nothing from the picture that actively contradicts the verbal portrait he delivers in his book. But this can easily happen in other contexts too.

Reading a German novel about the bombing of Dresden a few years ago, I found myself automatically googling a picture of a famous bridge that the novelist referred to in passing – an arched span of blue-painted ironwork, which, for some reason, I felt the need to look at directly, rather than just through the filter of her prose. And one of the reasons for that impulse, I'm pretty sure, was an odd desire to check that she'd got it right. Whether she had or hadn't didn't make a bit of difference to the novel itself.

Had it been an entirely invented bridge – rather than a real one that cropped up in an invented history – I wouldn't have felt cheated or mislead. But once I knew it was real I had to scratch the itch to look at it.

I've found myself doing it more and more, whether it's checking out the appearance of a particular kind of diesel locomotive while reading Alan Warner's The Deadman's Pedal or looking at Panoramio images of some of the Nigerian locations in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's recent Americanah. And I still can't work out whether this counts as an enrichment or an undermining distraction.

My prejudice is in favour of the latter, but I'm not convinced that prejudice is going to be able to do anything to enforce its disdain, and even less so as I read more and more on a page that can take me anywhere at the touch of a finger. The age of the unillustrated book is dead.

Gershwin overload gives me the blues

I Twitter-moaned a while ago about the knee-jerk instinct which provokes television producers into pairing archive shots of the New York skyline with Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue. Afterwards I wondered whether I'd overreacted, but then I sat down to watch Jay McInerney's Culture Show special on F. Scott Fitzgerald (tonight on BBC2 at 8.30pm) and within two seconds, those familiar swelling chords were surging across Manhattan streets. And yes... Gershwin is the epitome of the Jazz Age. But it's still a wretched cliché, worn into pointlessness by overuse. The only solution I can see is for the new DG to make it a sacking offence. Absolutely no exceptions.

Nervous breakdown at factory

It was ominous news that previews of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory had been delayed because of malfunctioning stage engineering. Not because they won't get it fixed in time for the first night but because the kind of complex stage-machinery that can push an opening back when it fails to perform is almost invariably a sign that the musical is looking in the wrong direction for thrills. I seem to remember a massively expensive bit of kit forcing the cancellation of the press night for the musical version of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, only to deliver a creaky, underwhelming coup de théâtre when it finally did perform. The levers and hydraulics that should matter most in these things are all inside the human body.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies