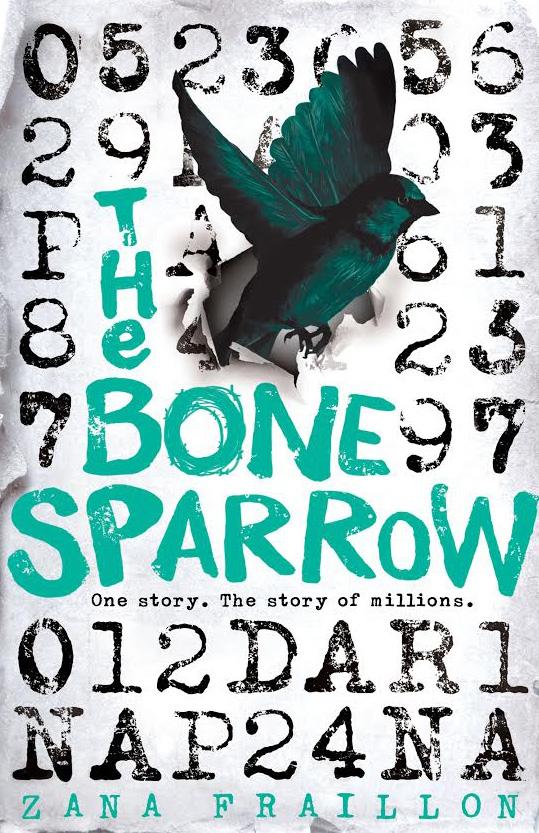

Book review, The Bone Sparrow by Zana Fraillon: A lone voice of hope in the horror of a refugee camp

- The Bone Sparrow by Zana Fraillon (Orion, £12.99)

Subhi is a member of the Rohingya people of Burma. Not that he has much cause to dwell on his homeland because he has never actually set foot in it. He was born in a refugee camp and his entire existence is defined by razor wire, and the casual brutality of the guards who oversee every waking moment. It is only in his dreams that Subhi breaks out and finds a universe of riches.

His days, however, are deprived and squalid which should make for depressing reading but Subhi is a cheerful soul with boundless optimism and an imagination as vast as the ocean he has never seen. He hoards stories like treasures and has a plastic duck by way of a friend, with whom he bickers companionably. In this way he makes his suffering, and that of his adored mother and sister, almost bearable.

Fraillon is an Australian who has given Subhi, whether intentionally or not, a vaguely Aboriginal lilt to his speech that makes The Bone Sparrow's narrative both musical and poetic.

“Some of the oldies ask me to draw them things. Sometimes they ask me to draw them things I haven't ever seen. And then they have to talk and talk until I can see in my head what they have in their rememberings,” he says.

Into this sea of deprivation sails Jimmie, who lives not far away outside the camp. We presume she is Australian as this is where many Rohingya refugees have actually been incarcerated but this is never explicitly spelled out. Jimmie and Subhi strike up an unlikely friendship after she finds a hole in the fencing. Emotionally adrift after losing her mother, Jimmie can't read and takes a precious book of her mother's to Subhi who is as hungry for new stories as Jimmie is to hear familiar old ones. In exchange she brings gifts of hot chocolate in a thermos and smuggled food, which astonishes Subhi's tastebuds, accustomed as they are to the daily gloop and slops issued by the authorities.

Subhi's endlessly sunny worldview masks the stultifying boredom of camp life, where there is no work, no entertainment and no succour of hope for a life beyond the razor wire. In a rare moment of despondency Subhi admits: “For years I didn't get it. That we aren't wanted in this place or in Burma, or in any other place. I didn't get it that we aren't wanted anywhere.”

This bafflement must be shared across the world by the dispossessed and persecuted who come seeking no more than compassion and shelter but are met instead with indifference and hostility.

This is a tragic, beautifully crafted and wonderful book whose chirpy, stoic hero shames us all. I urge you to read it

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments