Barbara Hepworth: A look back at the late great sculptor's seminal Italian adventures ahead of her Tate retrospective

'There is a whole new generation of art historian looking at her in different ways, and today you can present Hepworth without getting hung up on the fact that she was a woman'

The hollows and peaks of the West Riding of Yorkshire, and the elemental Cornish coastline, loom large in the life and creativity of the sculptor Barbara Hepworth, and galleries dedicated to her in both Wakefield and St Ives anchor her work firmly in England.

But, as an exhibition opening this month at Tate Britain sets out to prove, she strode an international stage. And an early episode in Hepworth’s career that made a huge impact on her, both as an artist and as a woman, explains how this process began.

In 1924, at the age of 21, Hepworth, the daughter of a civil engineer and a mother who made the clothes last with the help of her sewing machine, won a one-year travelling scholarship and set out from the Royal College of Art for Italy. “I arrived in Florence at night with only £9 in my pocket,” she writes in her captivating photographic memoir, A Pictorial Autobiography, written in 1970, five years before her death in a fire at her studio.

“The light at dawn was so wonderful in the eyes of a Yorkshire woman who had spent three years in London smog. This new light seized me, and I spent one year just wandering and looking everywhere …. I wandered round Florence, Siena, Lucca, Arezzo, basking in the new bright light and the new idea of form in the sun.”

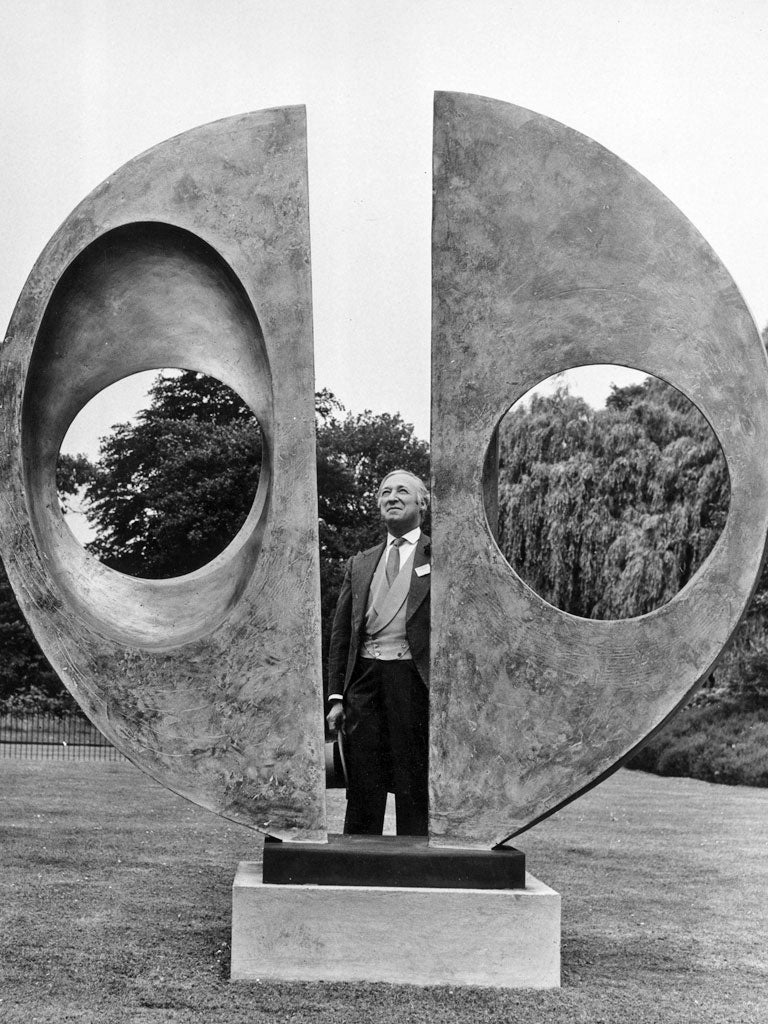

In Florence, she met a fellow sculptor, John Skeaping, whom she married, and with whom she would have a son, and together they learnt about marble: “I visited Cararra and studied the mechanics of moving weights,” she recalls. Making this connection with the size of work and material that dated back thousands of years would give her the confidence to work on a vast scale, later archive pictures showing an elfin figure standing by towering pieces, the juxtaposition undoubtedly pleasing her. But such success was a while coming: “We travelled home with a few carvings … and gave a private exhibition. Nobody came until the 14th day.”

Chris Stephens, who with Tate Britain’s departing director, Penelope Curtis, co-curates Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture in a Modern World, marvels at the distinctiveness of the young sculptor. “One of the striking things about Hepworth is that her modernity is not just in her sculpture but in her whole life,” he says. “For a girl from a bourgeois background in Wakefield to leave for Italy in her early twenties and get married was a bit out there.”

In Italy the artists she admired were not the grandiose and ornate – Michaelangelo, Bernini – but the earlier fresco painters Giotto, Piero della Francesca, and, above all, Masaccio, whose cycle of biblical scenes in the Brancacci Chapel on the south side of the Arno made the commonplace noble and the moment monumental. The talented young Wakefield woman who carved Figure of a Woman (1929-30) from Corsehill stone had surely been transfixed by Masaccio’s woman with a baby, appealing for alms.

Stephens believes this period is critical to Hepworth’s development. “She learns to carve in Italy from a marble craftsman in the place that has this millennia-old tradition of carving,” he says. “Central to her artistic identity is her carving. Henry Moore told the story that Leeds School of Art had to create a department of sculpture for him, but actually carving was quite common. Wood carving was especially popular with women in Britain – the material was easy to come by, affordable and easier to handle than some.”

One of the purposes of the exhibition, the first major London retrospective since her death, is to show Hepworth’s work alongside that of her peers, many of them forgotten, as well as illustrating her international reach. “There are new things to say about Hepworth,” says Stephens. “There is a whole new generation of art historian looking at her in different ways, and today you can present Hepworth without getting hung up on the fact that she was a woman.

“There’s a lot of interest in her place in the international scene, and in networks, and in how different artists got on with each other.”

When she returned from the protracted Italian stay in 1926, she had no work to show, so that the scholarship was never again offered to a woman artist, Hepworth being considered typically frivolous for returning with a new husband only.

But within 10 years Hepworth was at the heart of Abstract and Concrete, the great first exhibition of abstract art in Britain, which opened in Oxford and then toured in 1936. In the same year, André Breton opened the first British exhibition of Surrealism. Both movements were much enhanced by the steady flow into Britain of artists whose future on the mainland of Europe was looking perilous: it would be Hepworth’s lover then husband, Ben Nicholson, and his first wife, Winifred, for example, who arranged a safe haven in Britain for Piet Mondrian.

Hepworth and Nicholson’s substantial foothold on the international scene was enhanced by the highbrow and high-end art publications of the day, which disseminated images of their work worldwide. Even the more modest, gallery-going art-lover with no ambitions to collect was kept abreast of the latest modern art by respected articles in The Listener, the BBC magazine that was the intellectual home of a rising, post-war intelligentsia nourished by Workers’ Educational Association lectures and a massive programme of public art, from which both Hepworth and Moore received commissions, which emphatically and with civic pride put fine art at the centre of new housing and communities.

Although Hepworth had a special relationship with carving based on harnessing the material’s inherent properties and individuality – she said you could carve the same form over and over and it would always be a different sculpture – the show closes with some of her late bronzes: her triumphant 1965 show at the Krone Muller gallery in the Netherlands is partly recreated. But the earliest work shown dates from the first years back in London after her Italian adventure – a pair of marble doves. They could have flown out of a Giotto.

‘Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World’ is at Tate Britain (tate.org.uk), 24 June to 25 Oct. Companion exhibitions are at the Hepworth Wakefield (hepworthwakefield.org): ‘Hepworth in Yorkshire’, to 6 Sept; ‘A Greater Freedom: Hepworth, 1965-75’, to Apr 2016; ‘Plasters: Casts and Copies’, to May 2016, while the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden in St Ives is open daily throughout the summer (tate.org.uk/visit/tate-st-ives/barbara-hepworth-museum)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments