Concrete bungle: Exhibition of history of Milton Keynes fails to capture flawed urban experiment

Milton Keynes deserves more than a PR version of its futuristic roots

“Thousands of inverted buildings hung from street level – car parks, underground cinemas, sub-basements and sub-sub-basements – which now provided tolerable shelter, sealed off from the ravaging wind by the collapsing structures above.”

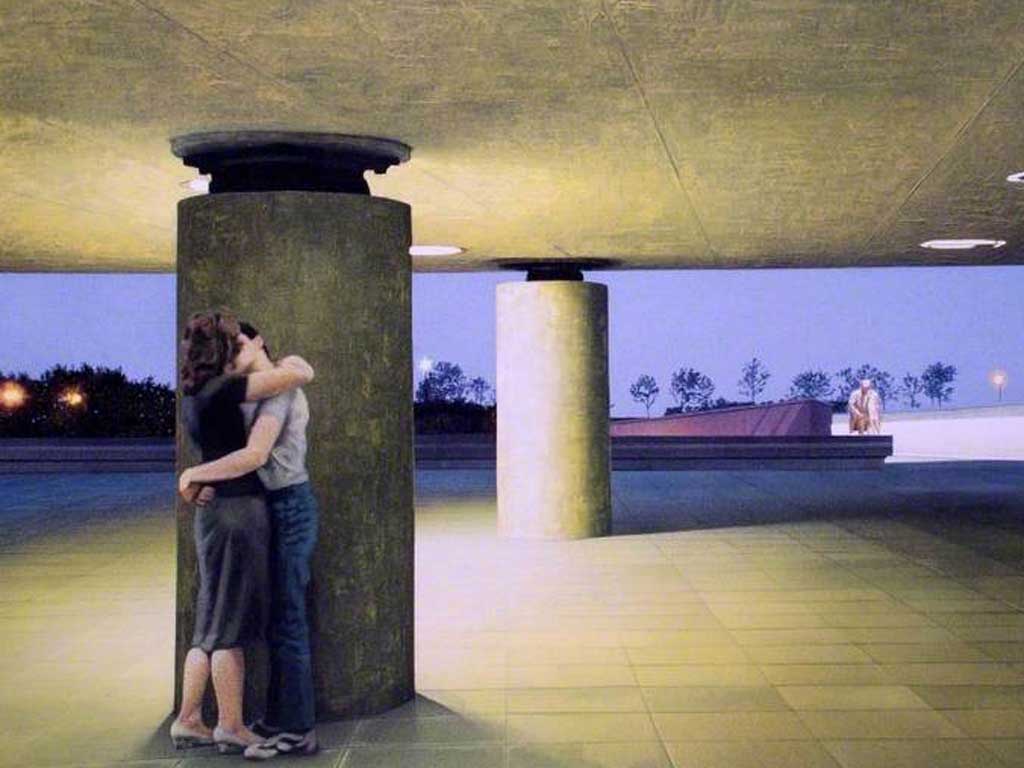

This passage comes from JG Ballard’s 1961 debut novel, The Wind From Nowhere. His vision of an upside-down world of brutalist post-war architecture is called to mind by a painting that hangs in the last gallery of this exhibition of the history of Milton Keynes, once dubbed “the little Los Angeles in Buckinghamshire”.

Underpass (1983) by Fionnuala Boyd and Leslie Evans is forceful and genuinely weird. It shows a young couple locked in an amorous embrace in a concrete underpass. The light that washes over them is a sour green, making the whole scene look unwell. The underpass is their refuge, as Ballard writes, although there are no ravaging winds here. There is a terrible stillness. Oppressive and impersonal, the setting is a shelter from the natural world.

At first glance, the painting looks like the kind of deliberately “bad” or “outsider”-seeming art produced by hipsters. But there seems to be no irony. Rather, there is menace. An older man in what looks like a flasher’s mac but might just be a quirk of early Eighties fashion is striding purposefully towards the lovers from the direction of the park. His head is down. He seems about to commit some furtive crime. Or perhaps the three of them have pre-arranged a Ballardian ménage-a-trois with a twist of unspeakable violence.

Underpass is successful in so far as it poses these fictional possibilities. It was painted while Boyd and Evans were artists-in-residence at the Soviet-sounding MKDC (Milton Keynes Development Corporation). Founded in 1967, Milton Keynes was the last and largest of the new towns to be built from scratch in the counties around London. The new towns experiment emerged out of the 1945 Welfare State and the belief that housing, health care, and culture should be accessible to all. In this way, the experiment was truly inspiring. It was far more radical than anything conceived in our own time.

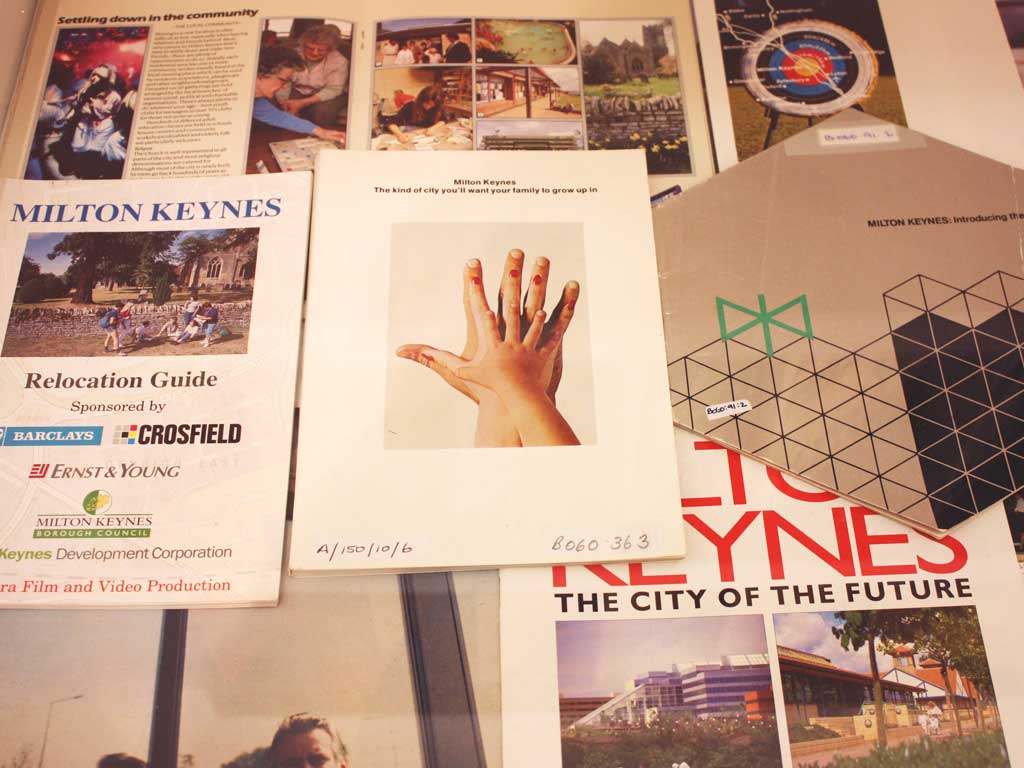

The problem with this exhibition is that it is too defensive. In a bid to disprove the damning view of Milton Keynes as a brutalist wasteland (the journalist Christopher Hooker described it in 1974 as “the utterly depersonalised nightmare which haunted Aldous Huxley just forty years ago”), the curator has tried to gloss over the sci-fi strangeness of the city in favour of a bland celebration of civic happiness.

The assortment of archive footage, memorabilia, specially-commissioned artworks, and architectural drawings are unsatisfying. The thrust of the exhibition feels propagandist, as though the curator is trying to entice the viewer to move to Milton Keynes. From an outsider’s perspective, the city is fascinating because of its utopian and dystopian qualities. “The English Garden City met American urban theory in the 1960s to create Milton Keynes,” explains the exhibition guide. But the absurdism of the venture is not explored. A little self-criticism wouldn’t go amiss.

The plans for Milton Keynes were both hyper-rational and cosmic: the main road was named Midsummer Boulevard and aligned to the sunrise on the summer solstice. The attempt to integrate nature and culture, park and city, was crazily conceptual. The American-style grid system of roads, promising egalitarianism and the possibility of infinite expansion; the shopping centre, one of the first American-style malls in Britain; the influence of Le Corbusier’s aesthetic austerity; the vision of a future in which people could enjoy “a wealthier lifestyle based upon motorised transport and telecommunications” – all this is amazingly rich and could be explored with imagination and depth. But it isn’t.

Underpass is one of the few works that permits any ambivalence about the city to emerge. This is a great shame. There are a lot of MKDC ads from the Seventies and Eighties, trying to dispel the negative image of Milton Keynes. One shows a horse in a paddock at dusk. The light is pink and the last rays of sun are disappearing over low-rise buildings in the distance. Beneath is the ironic slogan: Concrete Jungle. Rather than a sunrise, many of the images show a twilight state, the sun sinking. This contributes to the post-apocalyptic ambience of a brave new world that never quite was. Another ad shows a sunset over an artificial lake, luminous clouds scudding over a peachy sky. The slogan reads: The East End.

The ad is meaningful because many of the original new-town inhabitants came from the bombed out East End of London, rendered homeless by The Blitz. The new towns began out of a state of national emergency. By the time Milton Keynes was designed, the architects were keen to learn from their mistakes. New town blues had set in amongst some housewives who experienced a much higher level of material comfort and space than they could have hoped for in the city, but suffered from depression due to the soullessness of their surroundings. London’s East End was poor, crowded, sprawling, but it had emerged over centuries to become a layered and rich urban culture. There was closeness in the mess. In the new towns, there was, to borrow from Ballard, “the mysterious eroticism of the multi-storey car park”.

In Ballard’s vision, brutalism is fetishised. People are not alienated because of it. They exist in a symbiotic relationship with it. They are part of the concrete, they need it, they feed off it. One character in The Atrocity Exhibition (1970) is cold towards his lover’s body, but “the concrete landscape of underpass and overpass mediated a more real presence”. While the underpass in Boyd and Evans’ painting provides an ideal place of rendezvous for the lovers, elsewhere David Grandorge’s photographs show the undulating curves of an artificial ski slope that emulates the roundness and form of a female body. His photographs are compelling for their surrealism and their unusual focus on curves in a city of sharp angles.

Mound II (2013) is a large photograph of bushes in Milton Keynes. Not immediately prepossessing. The colours of the vegetation are autumnal: vivid reds and greens. In the background, a vast white mound is just discernible against a pale, cold sky. The mound seems to be a snow-covered mountain, which of course is impossible. In fact, it is an artificial ski-slope, looming and ominous. It is an emblem of the leisure and pleasure industries so lampooned by Ballard. The photograph is subtle and illuminating.

Plant (2013) by Grandorge shows the inner workings of the ski slope, viewed through a wire mesh. The lines of the funnel recall art nouveau rather than brutalism; they are graceful though grimy. The fact that the viewer sees the funnel through the mesh lends a note of zoo-like voyeurism. It is absurd to attribute a sexually sordid quality to a ski-slope funnel, but through a Ballardian lens that seems possible.

While Brasilia, founded in 1960, combined mythology with modernism to create a post-colonial and distinctly Brazilian identity, the cosmic overtones of the Milton Keynes project are gentler. Tom Emerson, co-founder of 6a architects, which is currently overseeing an ambitious expansion of the gallery, which will double its size and provide greater space for community participation, explains that Milton Keynes was rooted “not so much in mythology and modernism, but commerce and modernism”. He sees this as distinctly British: “We’re fundamentally a mercantile culture.” If Milton Keynes originated in the welfare state, it evolved throughout the Thatcherite Eighties. As Emerson points out, it was Thatcher who opened the iconic shopping centre in 1979.

This exhibition does not do justice to its subject, which is riveting. Blending so many ideologies, comprised of high glass walls that reflect back its inhabitants with eerie power, Milton Keynes deserves more than a PR version of its futuristic roots.

Future City, Milton Keynes Gallery (01908 676 900, mkgallery.org) to 5 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks