When Twombly met Rauschenberg: They firmly believed that art could change the world

Cy Twombly's retrospective at the Pompidou Centre in Paris is well worth the trip, says Karen Wright, who sees it in conjunction with his life long friend Robert Rauschenberg's exhibition at the Tate Modern

Cy Twombly was a remarkable artist. This large retrospective at the Pompidou Centre in Paris allows the viewer to have a literal panoramic view of his work, including drawings, photography, sculpture and paintings. It is a particularly fortuitous time to see Twombly’s work as his life long friend, and another extraordinary artist, Robert Rauschenberg, has a large-scale exhibition at Tate Modern only a short train trip away. Is it worth the trip? Yes, absolutely.

Twombly was born in Lexington, Virginia in 1928. The son of a baseball coach, he inherited the name of Cy after the baseball player Cyclone Young. It was clear from an early age he both loved art and had a natural talent and by 1950 he was in New York, having won a scholarship studying in The Arts Student League. He spent his summer in Black Mountain College, where he met fellow student Rauschenberg. In 1952 Twombly applied for a travel scholarship and with the resulting $1800 award invited Rauschenberg to accompany him to Europe and Africa.

The two, along with Jasper Johns, remained close friends for their entire lives often working in each other’s studios, leading to Twombly’s collective nickname: the “infernal trio”. He had even imagined their sub-title: “Three Dickheads from Dixie!”

Whether Rauschenberg, Johns or Twombly had physical relationships is beside the point (Twombly was to marry and have a child, as did Rauschenberg). What was clear was a meeting of the minds: both Rauschenberg and Twombly firmly believed that art could change the world.

One of the high points of the exhibition is Nine Discourses on Commodus (1963) – the series of paintings Twombly created in response to the assassination of John F Kennedy in 1963. The works take the name of Roman Emperor Commodus (161-192) who was known as cruel and bloodthirsty – often appearing in the Colosseum as a gladiator himself. These canvases were painted in Europe and shipped back to the US to be exhibited at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York City. They were met with critical disdain. Even Castelli said, “they were not really very good. They were very sort of Europeanised and precious.”

A retrospective benefit of them being unloved meant they were originally not sold and were shipped back to the studio in Europe where eventually a museum could purchase the entire series. At the Pompidou, these sparse works with their grey backgrounds, carefully controlled scrumblings and minute pops of pink and red relating to images of blood and a particular pink Jackie jacket, and thick impasto paint are grouped in one room. The power that emanates from them enfolds me.

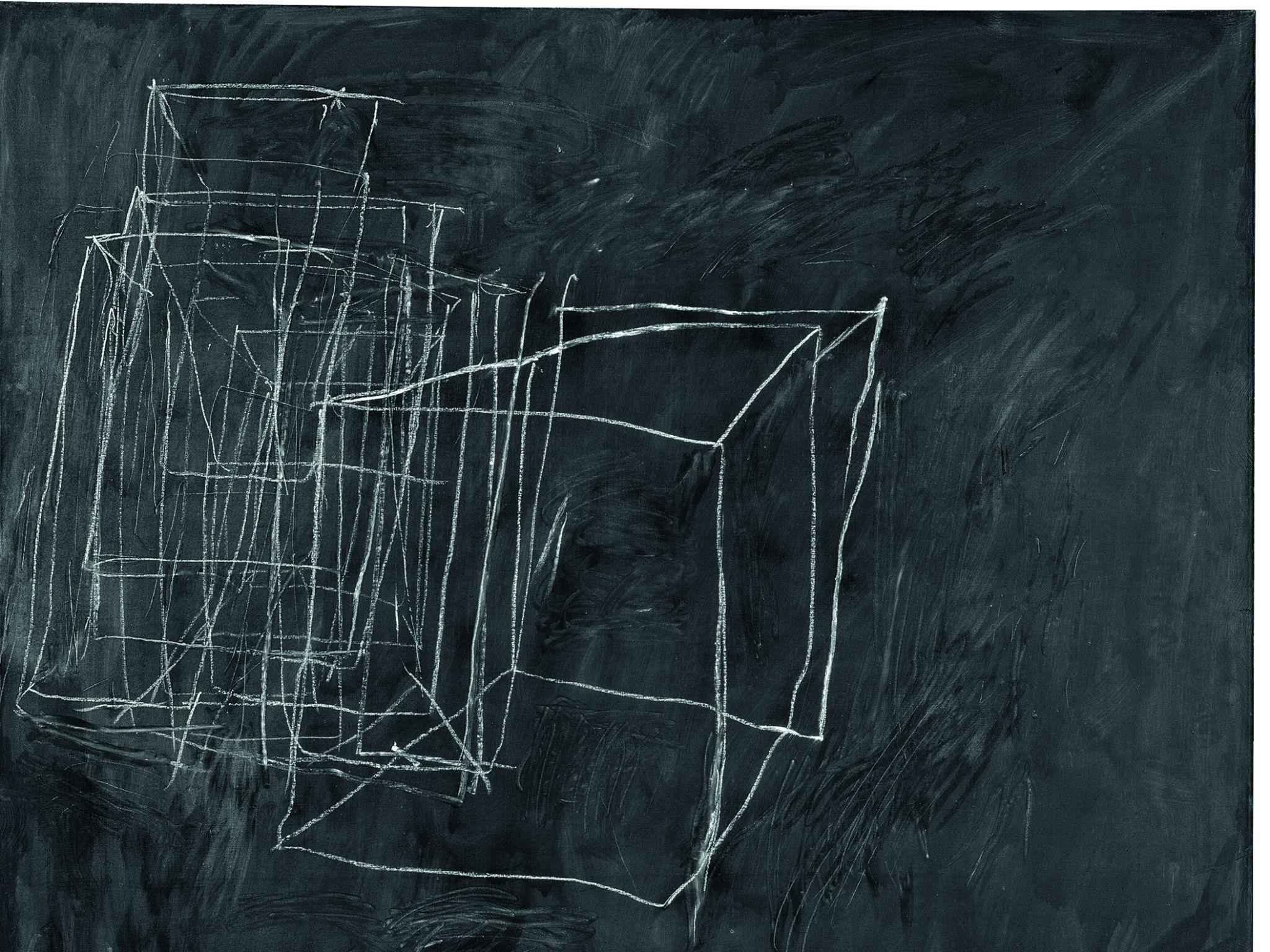

Twombly, however was not indifferent to the scathing remarks from his critics. He regrouped and moved away from the colourful palette to a more sombre grey and black tone, producing a group of works now referred to as “blackboard paintings” or “graffiti works”. A fanciful idea has often been suggested that Twombly was writing over and over, “I must be better, I must be better”. Perhaps he was also bowing to the overarching influence of the critic and artist Donald Judd and the increasing homage being paid to minimalism in America.

At the end of the large suite of rooms in the Pompidou comes a glorious moment when the viewer can see Paris spread below and also reflect on the work within. The curators have cunningly placed Twombly’s sculptures here. Twombly made sculptures throughout his life – transforming bits of rubbish found in his studio and holding the objects together with plaster incised with his trademark drawings and marks. Here one can fully understand and admire his forms, and his ability to transform detritus into representations of souls of boats and buildings, using only white plaster which he was to say was “his marble”.

On one of his trips to Italy in 1979 Twombly met botanical expert Giorgio Del Rosci who introduced him to Gaeta where he was to live and work for the rest of his life until his death in 2011(although he also kept a studio in his home town of Lexington Virginia.)

Twombly spoke of himself as a European painter and many of his art historical references, such as Jacques Louis David, Monet and Poussin, were European. Tellingly, in a 2008 interview with Sir Nicholas Serota before his exhibition at the Tate, he described himself as such: “You know, I don’t follow too much what people say. I live in Gaeta or in Lexington and I just have all the time to myself.” I remember the show at the Tate – visiting and revisiting it. Twombly was a painter who could represent emotions and events. I remember standing in front of the Lepanto cycle and being attacked by their strength. Something terrible happened there and you do not have to know the figures or numbers of deaths to feel that unleashed power.

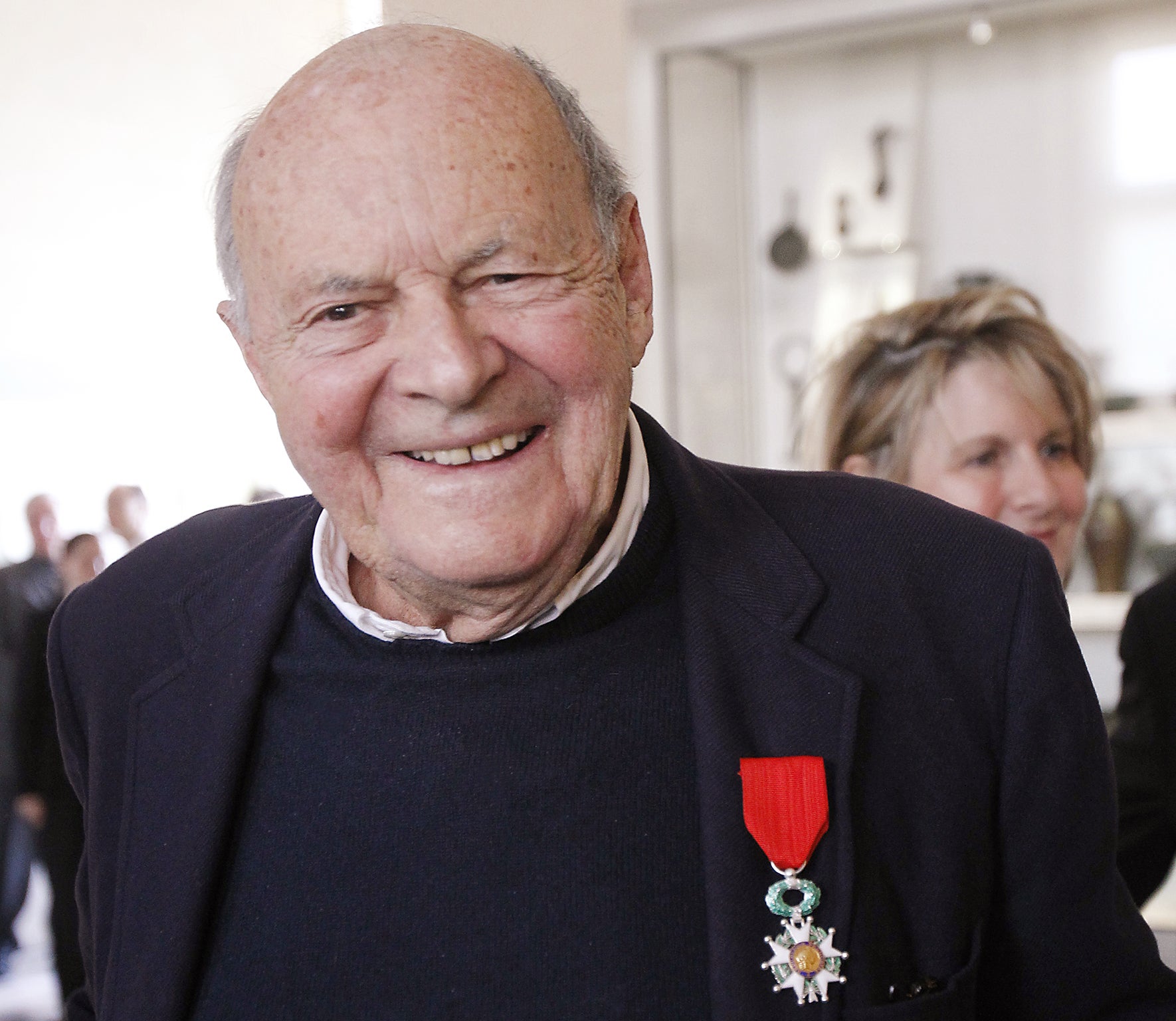

The untitled series, subtitled Bacchae, was painted shortly before Twombly’s death in 2011. In Paris at the press opening I listened to a young American journalist trying to elicit an admission that Del Roscio (who now runs the Twombly Foundation) and Twombly had a physical relationship. This has never been officially confirmed and this was not going to change that night. I finally interrupted the young irritating journalist to ask Del Roccio: “Did Twombly paint these huge paintings while standing on your back?” He replied by saying, “yes, that is true, they were large and it was hard for Cy to reach the top. It was important to paint them on the wall and not on the floor.”

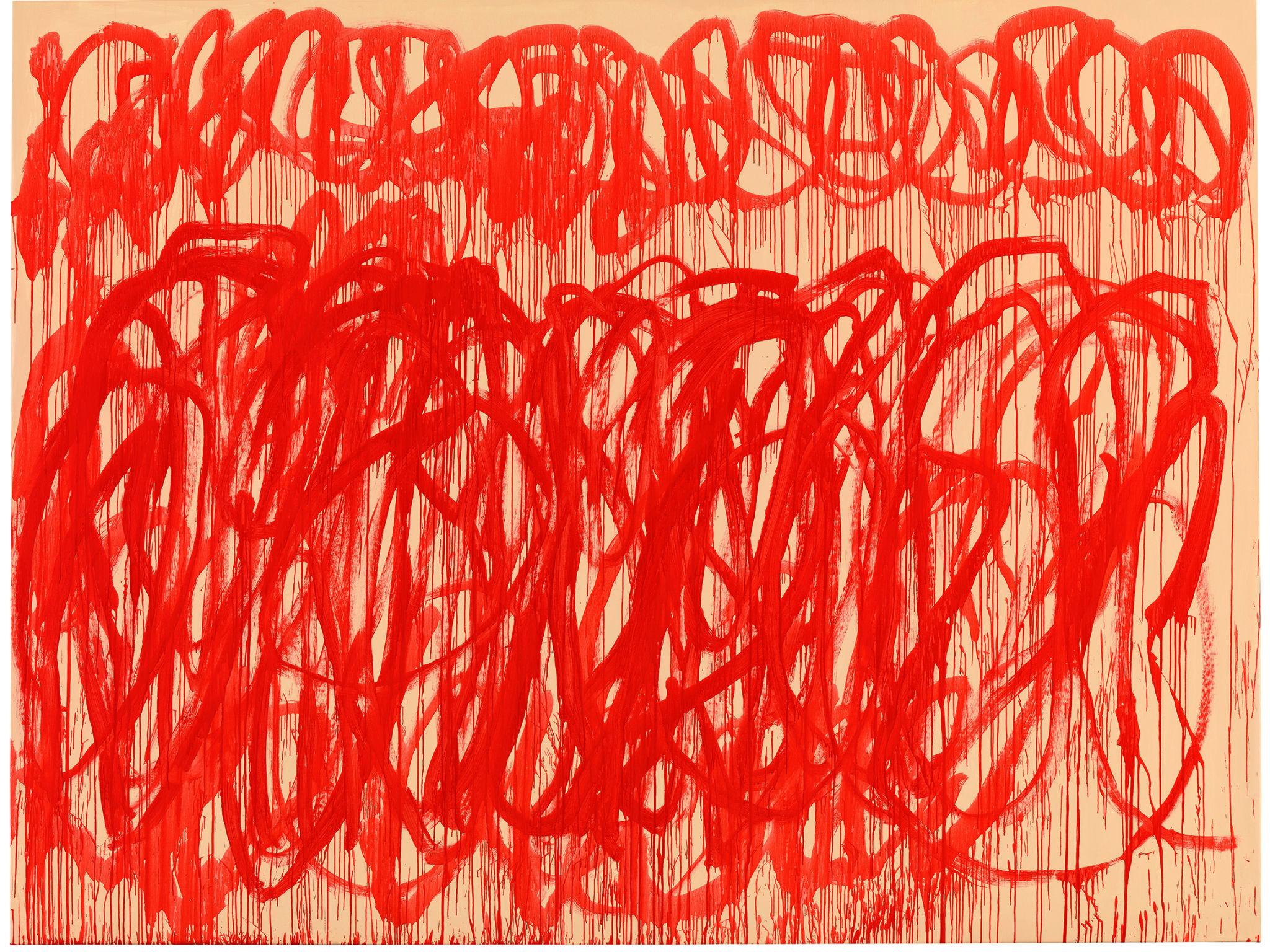

There is often much written about the diminishing power and quality of an artist’s later work – Willem de Kooning for instance, but there is no sign of a loss of power in Twombly’s late rooms. The Bacchus series, named after the ancient tragedy written by Euripides, are redolent of mortality and pain and will surely stand the test of time. Painted in 2005, at the time of the Iraq war, there are endless loops of blood-red paint, rich with the positive embracing of accidents of gravity, which Twombly would have learned from the best teachers such as Merce Cunningham and John Cage at the Black Mountain School.

In a moment of political uncertainty, here in England post Brexit and in America with Donald Trump about to assume the White House, voices like those of Twombly and Rauschenberg have become both increasingly important and rare. They believed that their work was important and, in some way, could change the world. Ironically it was Twombly withdrawing from America that led to his critical lambasting. I can just imagine Trump tweeting, “he is just a pansy who likes Europe. Let him go.” Get on that Eurostar to Paris and lift a glass of wine – preferably red – to Twombly .

Cy Twombly at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, until 24 April 2017 (www.centrepompidou.fr)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks