How early picture postcards were the Edwardian equivalent of Instagram

How social networking actually dates back to much earlier than initially thought, to more than a hundred years ago

Around the world more than three billion people regularly log on to the internet, and more than two billion are active on social media. Most internet users have at least five social media accounts – with the number of users tapping into social networks worldwide increasing by 176m in the last year alone.

With social networking apps, such as WhatsApp, Instagram and Snapchat, rapidly increasing in popularity, it can be hard to remember a time when these platforms weren’t a part of everyday life. And, although Instagram didn’t actually get going until 2010, people have been sharing photos and images of themselves for a long time – especially since the birth of the camera phone.

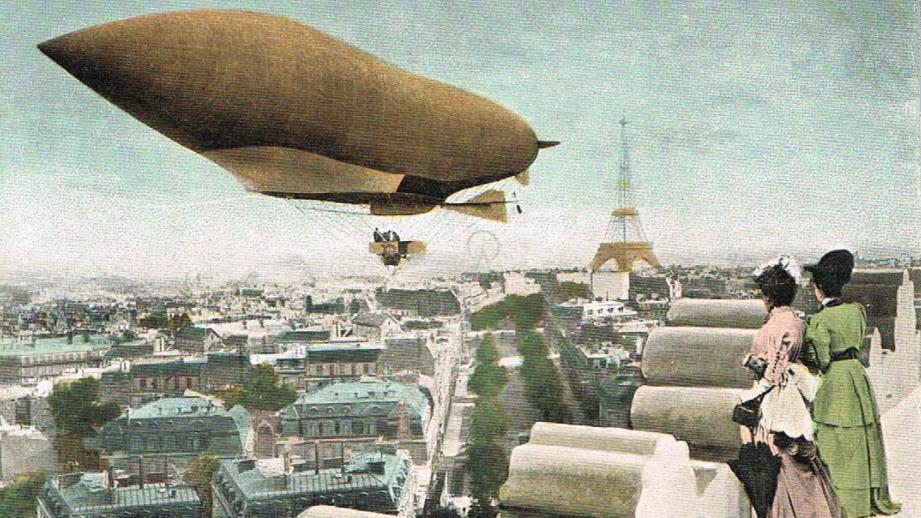

But now it seems this type of social networking, could actually date back to much earlier than initially thought, to more than a hundred years ago. New research shows that for our ancestors, the early 20th century saw a social networking technology that was unrivalled until the digital revolution a hundred years later. Because around 1894, the picture postcard arrived in Britain.

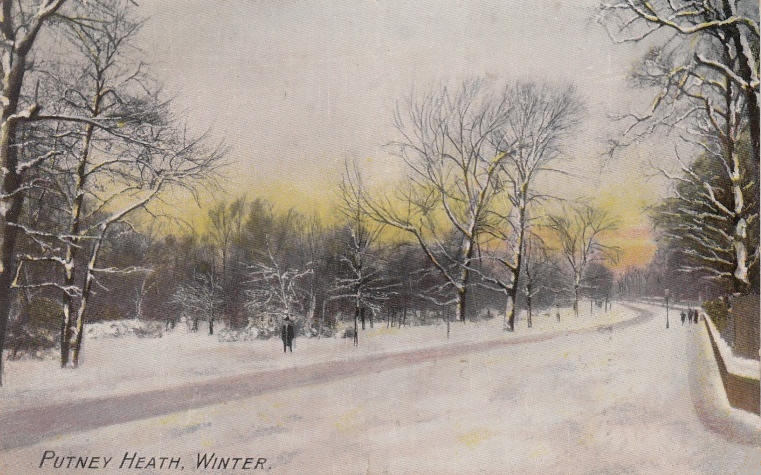

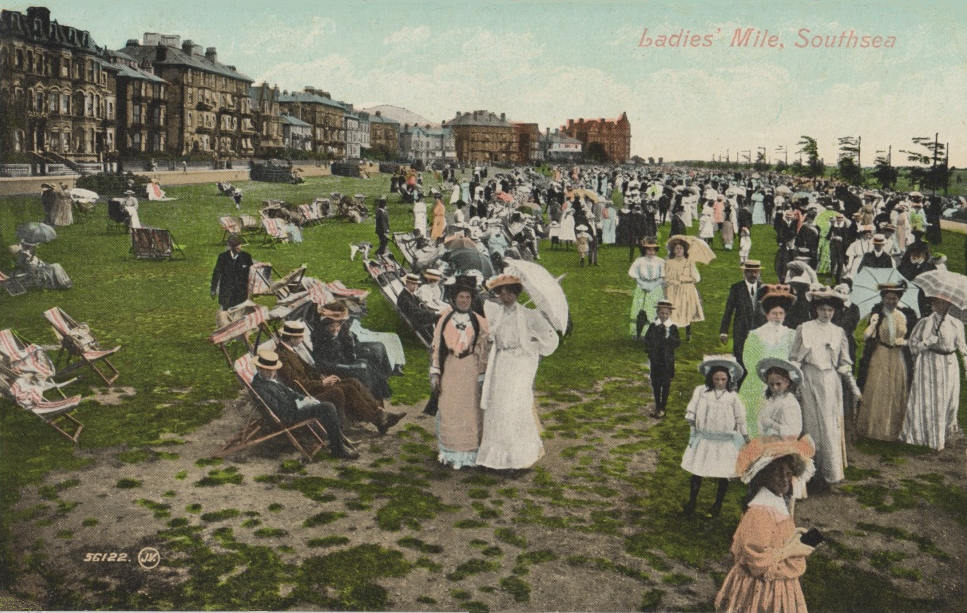

These postcards were very different from the picture postcards we know today. Rather than souvenirs sent home from holidays or bought in art galleries, these Edwardian postcards were used anytime, anywhere – as a way for people to keep in near-constant touch. Offering a vast choice of images, from cute cats, clergymen and sports stars to buildings and landscapes, they were more versatile than today’s postcards, and similar in many ways to platforms such as Instagram or Snapchat.

Wish you were here

People loved postcards because they could keep the messages short and send them whenever they wanted. They could be sent and received extraordinarily quickly – with up to six deliveries a day in large towns and cities, and even more in central London. A postcard could drop onto your mat anytime between six in the morning and ten at night – and there were even deliveries on Sundays.

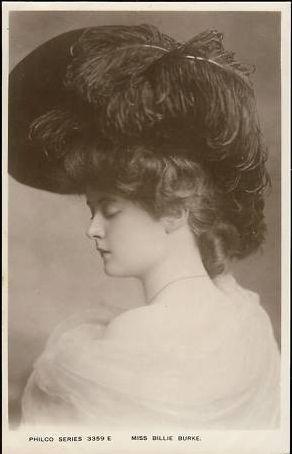

In 1894, picture postcards had become very cheap to buy and send, with a stamp costing a halfpenny – half that of a letter. Printing techniques were also developing fast so that by the turn of the 20th-century cards became imaginatively designed and colourful. Images were varied and publishers vied to produce new twists on popular memes, whether that was rough seas, baby animals or celebrities.

Every popular actress came to have a postcard contract as part of her drive towards becoming better known and as an element of her income. And if you did not like any of the images on offer you could even commission a “selfie” from your local photographer or produce your own.

At the very beginning of the 20th century, the Post Office was still insisting that the whole of one side had to be used for the address, which meant the sender only had a very small space to write their message. But in 1902, the Post Office relaxed its rules, making Britain the first country to introduce the “divided back” – the same format we use to this day.

This saw the picture postcard become even more popular – with the Postmaster General’s report revealing that six billion postcards were sent between 1902 and 1910. This is roughly the equivalent of every person in the UK sending 200 postcards during that time.

Travelling tales

Postcard users received, as well as wrote, cards while travelling, just as we use social media to share snaps of our holidays today. When writing their cards, some drew on letter writing conventions they had been taught at school, beginning their cards with their own address followed by “Dear Mr or Mrs”, but far more people took the opportunity to free themselves from those constraints and wrote informally.

In the same way we use social media today, many postcard senders, didn’t bother to sign off their name at the bottom of the card, as the receiver would already know who the card was from. And many of the card messages were brief, because they were dashed off quickly, just as we might send a text or WhatsApp message nowadays to let someone know where we are.

Fading memories

Over time, the postcard gradually declined in use, because of higher costs, fewer deliveries and, it must be said, improved working conditions for the severely overworked postal carriers and their horses. But it would be many more decades before the telephone became accessible to the masses and people could easily speak to one another at a distance.

There was nothing comparable to the Edwardian picture postcard in the period between 1910 and the dawn of electronic social media. And no similarly accessible and attractive form of fast written communication was possible until the development of digital platforms.

Despite the decline in popularity of postcards today, they continue to be a significant part of British seaside tourism. Sold by newsagents and souvenir shops, modern postcards often feature photographs of the resort in beautifully sunny weather, with deckchairs a plenty – and echo a bygone era of early social media.

This article was first published in The Conversation. Julia Gillen is Senior Lecturer in Digital Literacies, Lancaster University.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks