Mexico's train of death: Entry into the Land of the Free isn't merely unlikely – it's potentially lethal

The photographer Nicola Okin Frioli tells Linda Sharkey about the journey faced by hundreds of thousands of undocumented Latin American immigrants

Battered, scarred, mutilated – all in pursuit of the American dream. The physical and psychological wounds suffered by the people on these pages might take different forms, but each was endured as part of a desperate bid to escape Central America in search of a better future.

Each year, hundreds of thousands of undocumented Latin Americans from Honduras, Ecuador, Guatemala and Nicaragua – some fleeing violence and economic hardship, others wishing to be reunited with family members – are confronted by the threat of corrupt authorities, dangerous gangs, kidnapping and sexual assault as they make a journey across Mexico to the United States border. Yet still they come, the majority to take their chances with "The Beast".

The freight network that crosses Mexico, also known as "El tren de la muerte" ("the death train"), is one of the very few ways immigrants can avoid the myriad checkpoints and 48 detention centres on the way into the promised land – yet the risks of riding it are precipitous. The 1,450-mile journey that typically begins in Arriaga, Chiapas, in the south of the country, requires the migrants to board, ride on top of, and leap from up to 15 different trains – and accidents are not uncommon, from lethal falls while asleep to the loss of limbs in mechanical calamities.

Yet, as an immigrant himself, the Italian-born, Mexico-based photographer Nicola Okin Frioli asserts that he can understand why these migrants attempt this most perilous of expeditions. "I, too, moved from my native country in search of fulfilling my dreams," he says.

Frioli moved to Mexico in 2007, and in his series "The Other Side of the American Dream", he aims to "look into the eyes" of those who have attempted to make the crossing but – like the vast majority – failed. The 70 shots in the series portray the migration's most unfortunate victims and the objects they took with them for emotional and physical support – from rosary beads to a bottle of water with a string, as "they need their hands to hold on strongly to the Beast".

For six years, the 37-year-old photographer has found his subjects in shelters for those who have fallen by the wayside, run by priests and aid workers in Tapachula, Chiapas, a city near the Guatemalan border, and Ixtepec, Oaxaca, in southern Mexico. Frioli has been threatened by gangs numerous times, but managed to complete his task with the assistance and protection of anti-censorship organisation Article 19.

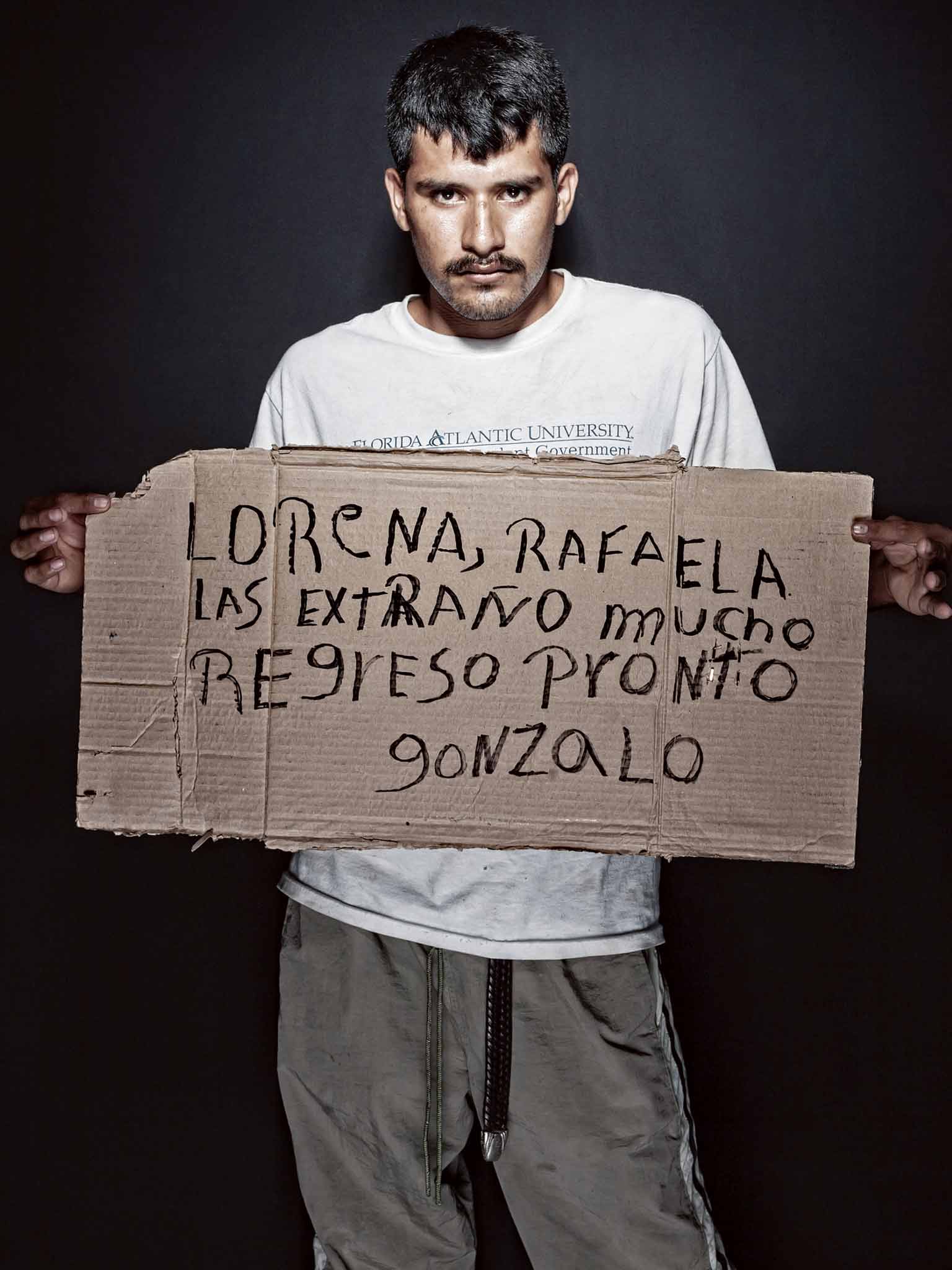

Each of his images comes, naturally, with quite a story. Gonzalo, from Honduras, is pictured with a message for his wife and daughter that reads: "Lorena, Rafaella, I miss you lots. I'll be back soon." "When I saw it through the lens, I couldn't help my tears," comments Frioli. "It was such a simple yet powerful message; he was so convinced he would fulfil his trip safely."

Yenifer, an eight-year-old girl, suffered a car accident with her sister. "I felt such pity to see an innocent girl with a bruised face," says the photographer. "The look in her eyes was like she was clueless about what was next."

Teofilo Santos Rivera, 42, a Panamanian, was the victim of an attempted mass assault by gang members during his crossing through Mexico. "He was suffering from liver cirrhosis and a cancerous sore on the back," Frioli recalls. "In January 2014, the doctor gave him 40 days to live, but he wanted to reach his children and grandchildren in the US to say goodbye. He jumped off the roof of the train, hurting his feet.

"I saw him in the shelter in January and again in March. He was clearly stranded. I will always wonder whether I was the last person to take a portrait of him."

Frioli now hopes to "glorify the project with a book" – but more than that, the consequence of his six years of work is that he admits he will forever want to know "whether these people reached their destination safely".

Nicola Okin Frioli was supported in his project by the bank BBVA. For more from the series: nicolaokinphotography.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks