Paul Strand: V&A exhibition shows how photograper captured hitherto hidden aspects of Britain and Europe

In Strange and Familiar at the Barbican, Strand’s vision of South Uist has a kind of outlier status

In 1954, the American photographer Paul Strand went to South Uist in the Outer Hebrides to work on a photo-book entitled Tir A‘Mhurain (“the land of bent grass”). A BBC radio programme with Gaelic folk-songs had attracted him to this remote spot – as well as proposals to use the island as a testing site for US nuclear missiles. An idealistic socialist who lived in France from 1950 after McCarthyite harassment at home, Strand had begun a long series of intensive, contemplative studies. They took him to places – Italy, Egypt, Ghana – where traditional ways of life confronted the threats, and lures, of modernity.

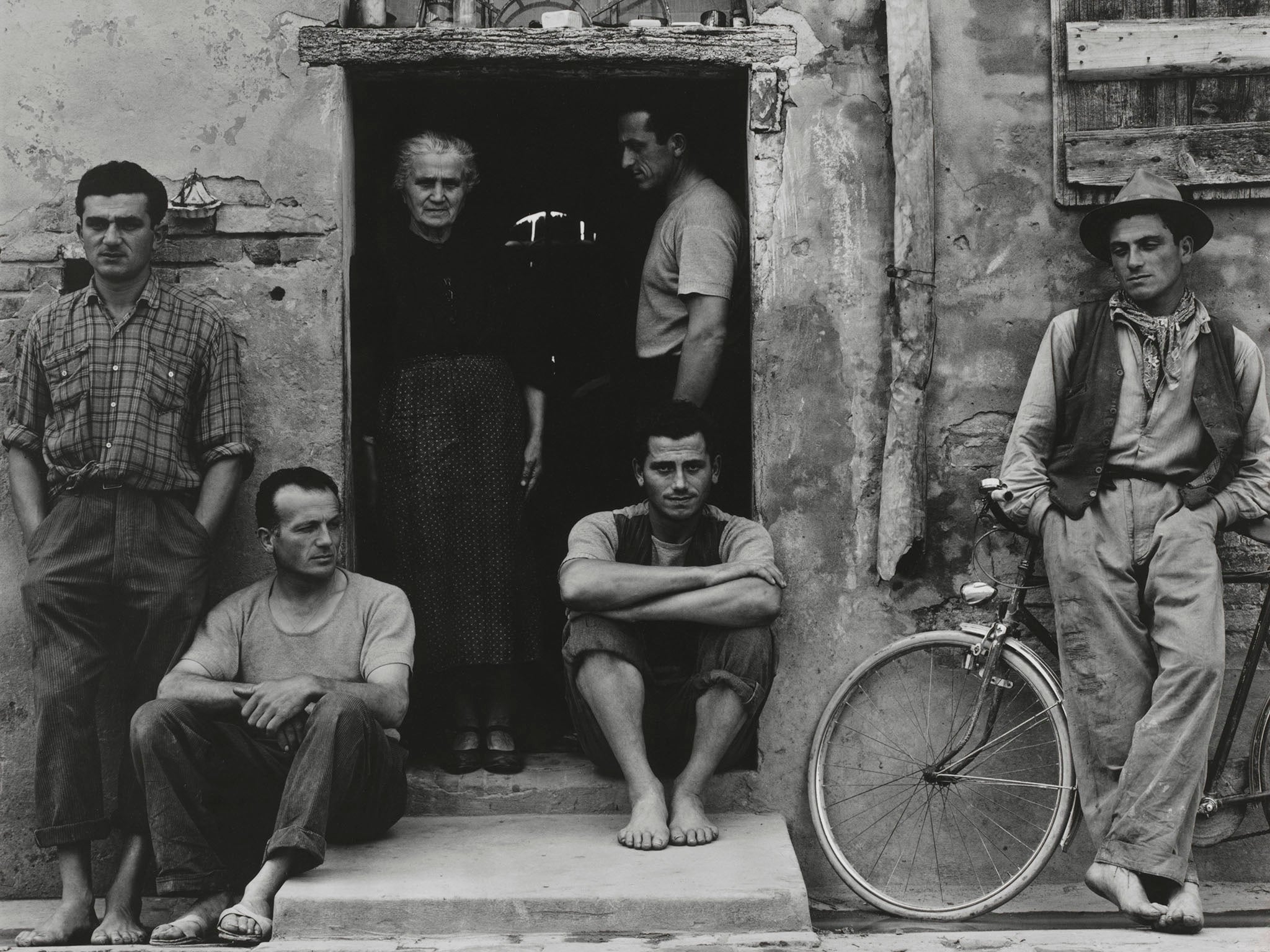

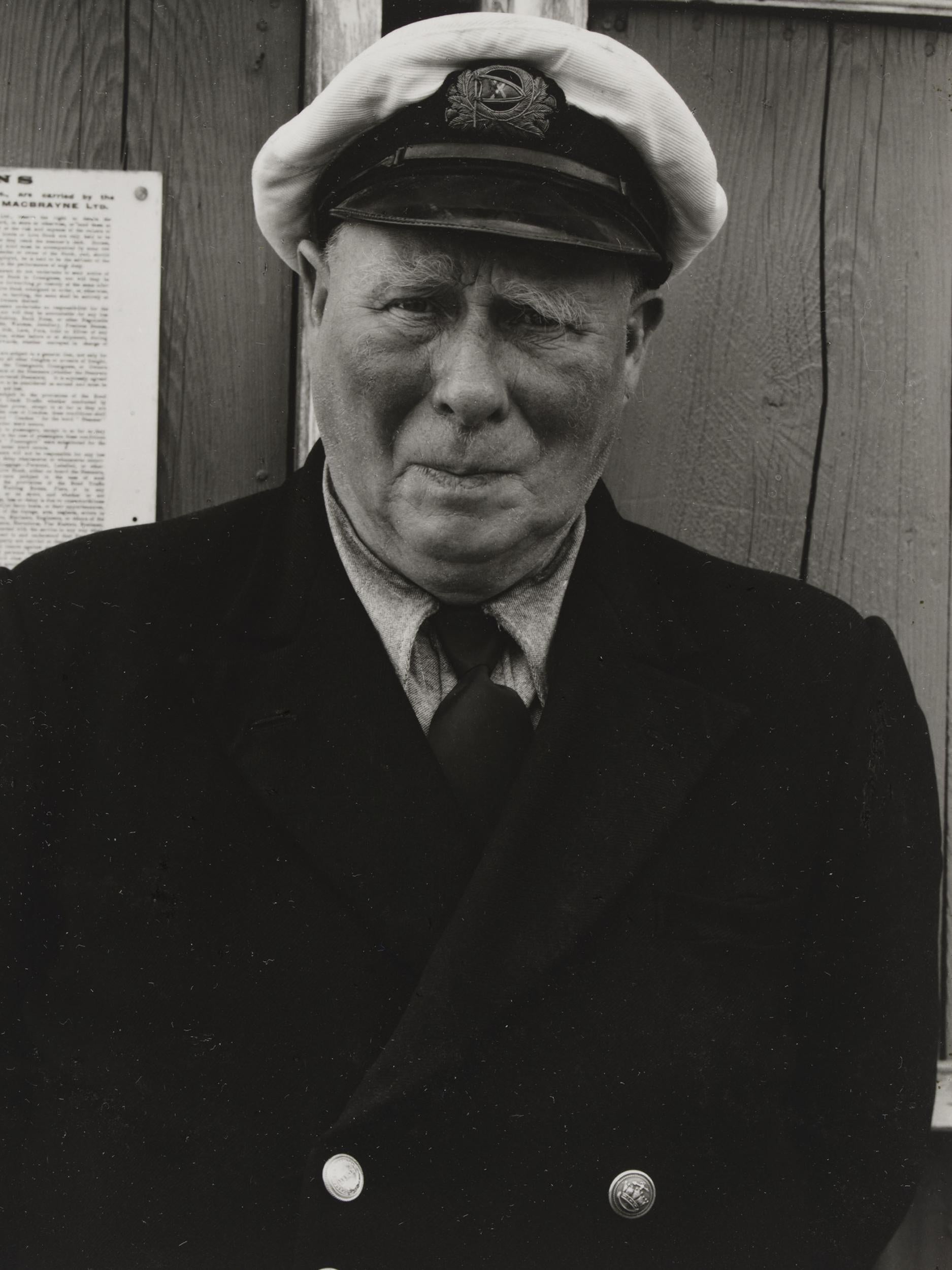

The books that harvested his densely textured black-and-white images came with commentaries by notable writers: in this case, the historian (and wartime SOE secret agent) Basil Davidson. On South Uist, Strand created grainy close-up still-lifes and uncanny landscapes of grass and sand and shrubs; studies of weathered cottages under spectacular skies, or horses standing on the endless beach. They alternate with dramatically lit and composed formal portraits. In them, Strand renders the islanders – these proud MacDonalds and MacLeans and MacIntyres – as grand and enigmatic as Renaissance nobility.

To have one glimpse of Strand’s Hebridean voyage would be a privilege at any time. Thanks to one of those curious synchronicities that happen in the gallery and museum world, two flagship venues in London now host pictures drawn from the same project. At the V&A, pictures from Tir A‘Mhurain contribute to a generous overview of Strand’s entire career. Over at the Barbican Art Gallery, meanwhile, Strand counts as just one of the 23 international figures gathered by curator Martin Parr into a vast and varied survey of Britain viewed by visiting and expat photographers through their own subjective lens.

The V&A’s Strand retrospective passes from Manhattan street life in the 1910s through a quasi-Cubist period in the 1920s and on to his life-changing years in Mexico. There, work in both still photography and documentary film turned the New York avant-gardist into a radical arts activist who somehow never lost his classical eye for felicities of shape, light and structure. In a sunlit New England picket fence, on the shadowed walls of a derelict factory, or through the sculptural grandeur of a peasant-family portrait, Strand makes form and history converge. Behind these artful compositions lies the work of time, and power.

Like many restless artists of his age, Strand felt the pull both of modernist purity and documentary realism. Unlike most, he found a way to harmonise these rival impulses. That time-worn farm door in New England, or that cluster of gossiping locals gathered in a shady café in provincial France, hint at the deep patterns of the past. With tactful artistry, he employs a kind of visual metonymy – where the selected image stands for the entire narrative. As a people’s champion rather than a lofty aesthete, however, Strand needed those books to tell the whole story that he saw. Photography curators have a bad habit of wrenching images from their context and inviting viewers to misread them. Here, Martin Barnes and the V&A clarify the role of these pictures within a wider narrative of continuity and change.

In Strange and Familiar at the Barbican, Strand’s vision of South Uist has a kind of outlier status. Unpeopled vistas and rural communities seldom feature in the work of these quizzical and bemused observers. They tend to focus on the street life and social rituals of a fast-changing urbanised society, post-colonial and post-industrial. Yet private insight often outweighs public reportage. If you come to the Barbican merely for state-of-the nation diagnostics and polemics, you may leave frustrated or baffled. All British life is certainly not here.

Nor should it be. Rather, Parr has collected 23 individual testimonies. They range from Strand’s bomb-shadowed Hebridean idyll to Henri Cartier-Bresson’s slyly comic sequence of royal ceremonies (from 1937 to 1977) and Raymond Depardon’s anguished yet beautiful scenes of Glasgow slumland life in 1980. Oddly, what you won’t find in abundance is the kind of offbeat commentary on suburban life and Middle English manners – wry, satirical yet affectionate – that has often driven Parr’s own work. In the catalogue, he writes: “What a shame that you cannot photograph Radio 4.” With a couple of exceptions, our keen-eyed visitors miss the Britain that loves and embodies Radio 4.

They train their lenses instead on class conflict and industrial decline; on subcultural trends and multicultural movements; on toffs and beggars, miners and migrants, Beats and hippies. For every Depardon, who in livid colour finds gestures of hope and defiance (usually from children) amid the crumbling tenements of Glasgow on the eve of its revival, a Tina Barney will dress upper-crust grandees in formal poses that recall the ancestral portraits hung behind them. Foreign eyes do seem to prefer a vividly stratified country of duchesses and dossers. The subtler shifts in middle-class life that have fuelled broader social change prove more elusive to the outsider lens. Drama, contrast and motion make the shutters click – whether in the German Frank Habicht’s scenes from trendy but innocent “Young London” in 1969, with its parties and squats, demos and gigs, or the American Bruce Davidson’s brilliantly angled and framed shots of Soho night-birds or Welsh mining-village nuptials.

As with Strand’s work, many of these British views first appeared in photo-books alongside texts that sought to explain or expand upon them. A good example is the American photographer Evelyn Hofer’s London Perceived (1962). Her gently humorous but celebratory portraits of cabbies and porters, of Smithfield Market and the Garrick Club, run beside an account of his beloved city by the great short-story writer VS Pritchett. Parr collects these books, and the displays in Strange and Familiar – as at the V&A – take care to show how image, word and lay-out worked in sync.

You may treat each photographer as a witness and chronicler of the big British stories about class and industry, poverty and wealth, migration and rebellion. For sure, our spectacle of inequality still flourishes. Here, it re-plays all the way from the Jewish refugee Edith Tudor-Hart’s tender shots of babies and families in the 1930s East End to Bruce Gilden’s outsize and harshly lit working-class portraits from the Black Country in 2014. No one can doubt Tudor-Hart’s respectful engagement with her disadvantaged subjects. Gilden belongs to a cooler, more detached epoch. Unforgivingly exposed, these warts-and-all Midlanders defy us to honour them in the way that Tudor-Hart, Robert Frank – or Strand himself – would have done in shots of ordinary folk. The implicit cruelty may belong not so much to the artist as to our winner-takes-all age.

Elsewhere, social criticism gives way to personal journeys through the city. Quick-fire street sketcher Gary Winogrand brings his unsettling sensibility – a kind of bebop photography – to Sixties London and disrupts its cliches. In the late 1950s, the Chilean Sergio Larrain transforms the London winter into a lurching film-noir dream. Candida Hofer travels from Germany to Liverpool on the trail of the Beatles’ paradise of fun and finds the eerie twilight of a once-great port. From Italy, Gian Butturini makes the capital’s first Summer of Love wobble and warp like an acid trip.

Somehow, the visionaries see deeper than the sociologists. Shinro Ohtake from Japan wanders through London in the punk heyday of 1977 and does much more than annotate “a city mired in economic hardship” (as the Barbican’s over-emphatic publicity states).The ever-changing theatre of the street bewitches most of these 23 hawk-eyed guests. But not Dutch photographer Hans van der Meer. He sets up his chunky camera on a stepladder and takes panoramic colour shots of amateur football games across the North. The pictures are weirdly enchanting: fresh versions of pastoral in which the moors and dales of Pennine counties serve as a moody backdrop to the weekend pathos and heroism of local leagues. One match takes place in Ted Hughes’s home village of Mytholmroyd. In a show richly endowed with star overseas strikers, Van der Meer’s stubborn patience somehow scores a very British goal.

‘Paul Strand: Photography and Film for the 20th Century’ is at the V&A, London until 3 July: vam.ac.uk; ‘Strange and Familiar: Britain as Revealed by International Photographers’ is at Barbican Art Gallery, London until 19 June: barbican.org.uk/artgallery

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks