Picasso: Are we doing it to death?

‘Picasso 1932 – Love, Fame, Tragedy’, which opens at Tate Modern next month, consists of paintings, sculptures and drawings made in an intensely creative single year. Michael Glover wonders whether that might not necessarily be a good thing

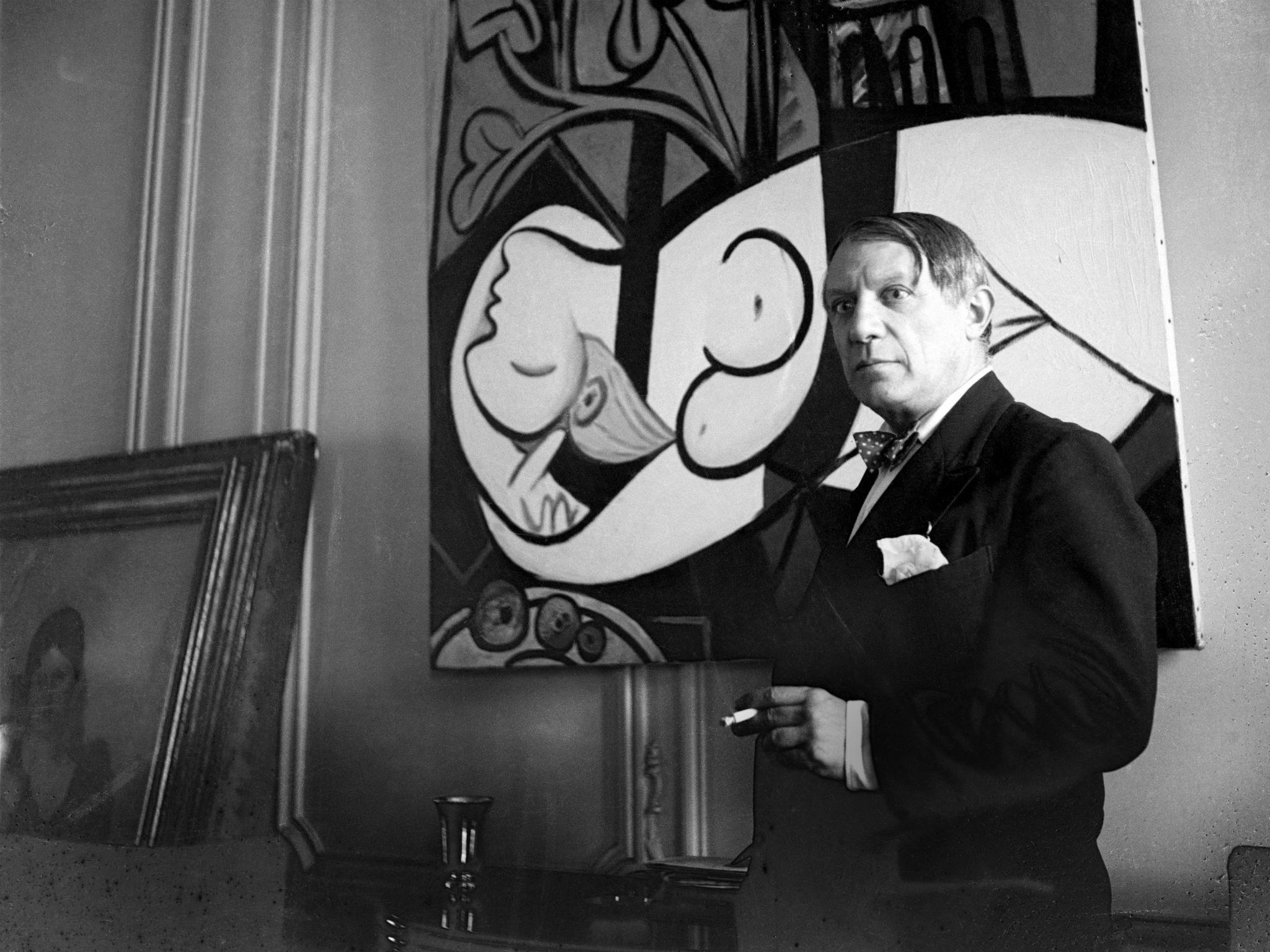

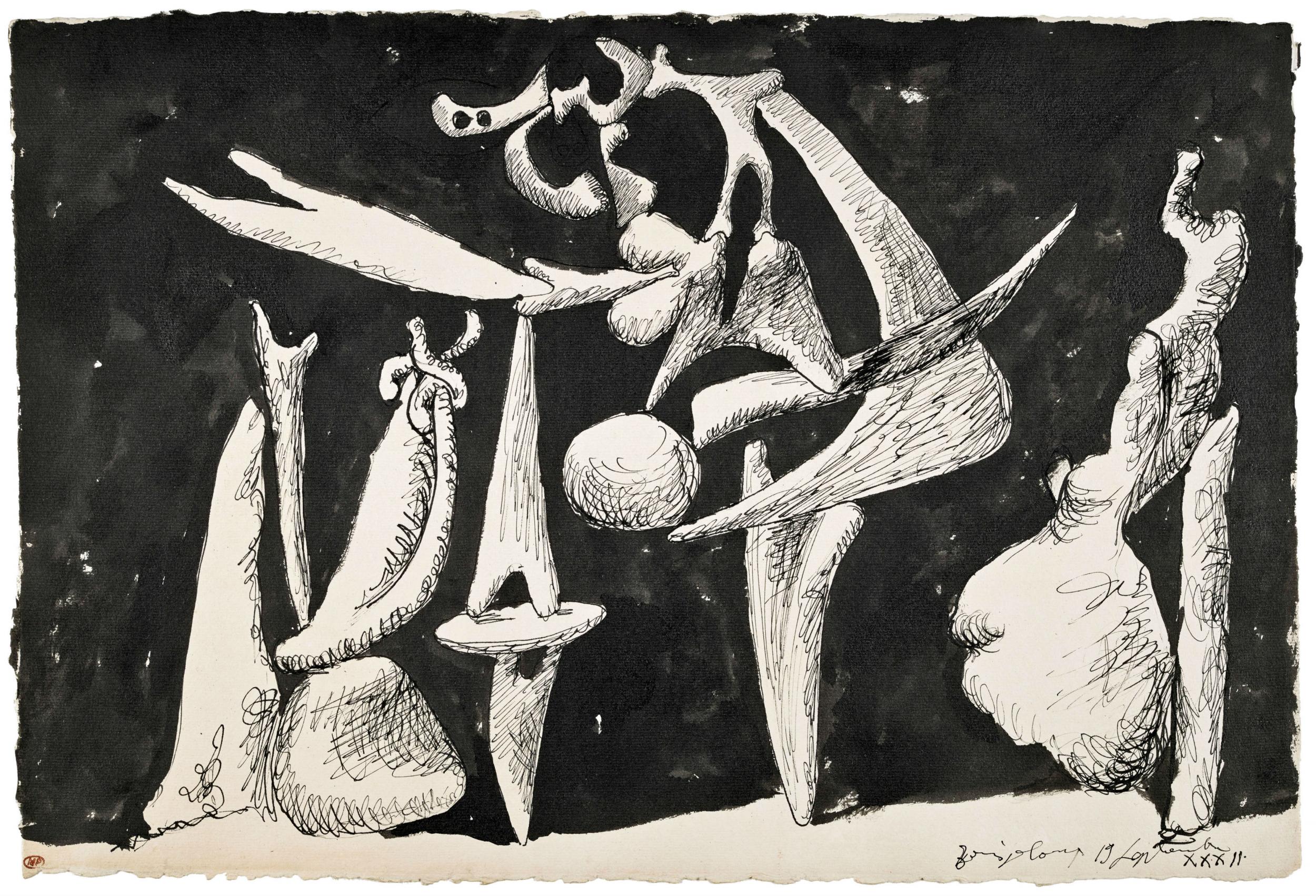

It’s Picasso hour again! Next month, Tate Modern is putting on a show which will consist entirely of works produced by the small Spanish maestro in 1932, a single year. An entire show of more than one hundred works from a single year! What an extraordinarily productive man he was. He wasn’t even so young by then either – 51. The fact is that he never stopped working.

His great biographer John Richardson once told me all about it, at a press conference for a huge show of works by – you’ve guessed it – Picasso, which happened at Gagosian Gallery in London. “He would work all day,” he said, “and then, after dinner, at about 10 o’clock, he would often go straight back to his studio and work until four or five in the morning. I would say that on average he made three objects a day, every day of his working life, which continued practically until the day of his death.”

Now if you make three objects a day for your entire working life (it started very young, and it continued almost until he died at the age of 91), how many works would that give you in all? One of the best ways of finding out is by consulting the catalogue raisonné that an old friend of his called Christian Zervos began to publish in 1932, in collaboration with Picasso himself. By the time it was finished – there were 32 volumes eventually – it listed 16,000 paintings and drawings, of which more than 10,000 are paintings. How does this output compare with that of other artists? Here are a few numbers: Vermeer made a total number of 34 paintings; Titian: approximately 1,500; Leonardo de Vinci: 15.

Picasso wasn’t always regarded as an unstoppable force of nature. Let’s wind the clock back a little. In the 1950s when David Hockney was at art school, Picasso was widely disliked and even vilified by the critics. Hockney, that lippy young Bradford student, sticking his neck out in characteristic fashion, loved his work and championed him. Many continued to disagree. Picasso’s late works were much disliked for their so-called childishness. He was criticised for revisiting old themes, and even for repainting the same subjects brashly and crudely. The work of the post-war period was generally regarded as inferior to much of his earlier work.

Little by little, all that has changed. The work produced after the Second World War now gets a much more favourable press. His late work is now said to possess a wild, childlike vitality – a very positive way of looking at it. And certainly no one criticises Picasso for his infidelities. Geniuses get up to what geniuses get up to. He seems to be magically ring-fenced from much criticism of any kind. Here’s an interesting comparison of the way two reputations have been treated.

You could argue that one of the keys to Picasso’s positive approval rating by the world at large has to do with his moral authority – and here I am referring to something much more elevated than mere canoodling in a bed. He is still regarded as an exemplary figure in certain important respects. That press conference at which I talked to his biographer, Richardson, was also attended by Picasso’s grandson, Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, who is in charge of the Picasso Foundation. Ruiz-Picasso spoke about Picasso’s heroic decision to remain in Paris during the Second World War, of his support for the resistance, and of the fact that by staying put in occupied France he became a beacon of liberty during those dark days. Richardson, taking up the theme, mentioned his generosity to Spanish artists, of how he would help the needy – much of this generosity has gone unrecorded, he added proudly.

There is, of course, another way of looking at Picasso’s “heroic” decision to remain in Paris during the Second World War, and this was put to me, with some vehemence, at the Salvador Dali Museum in Figueres some years ago. I remember to this day how furiously the Dali apologist attacked me when I mentioned the name Picasso. Oh, so he was a hero for living alongside the Nazis!, he spat across the table. Why then was Dali such a traitor for living in Spain under Franco! Was he more or less of a collaborator than Picasso?

And then, of course, there is the Picasso who spoke so little about his own work. All he did was to make it, day in, day out. That is very convenient, as it happens. No matter what you say about Picasso, you are unlikely to find written evidence that he profoundly disagrees with you.

The fact is that the more Picasso comes to be regarded as the greatest artist of the 20th century, the more his works will increase in value – nothing surprising about that. A more surprising consequence of this general upward mobility of prices, hand in hand with reputation, means that even more works by him will go on show in exhibitions. How so? Because the more an artist is seen to have been blessed with the Midas touch, and the more important he becomes, the more you will go looking for yet more examples of the same because you will want to tell as much of the story as possible. Success breeds success. Curiosity breeds curiosity. Last year the National Portrait Gallery staged a show of Picasso’s portraits. Once upon a time, some of these portraits would never have been included in such a show. They wouldn’t have been good enough. They were unremarkable caricatures on pages of old newspapers – Picasso’s newspapers, of course. He was a great hoarder.

Now, such is Picasso’s influence and reputation, that everything deserves very close attention these days, the good, the bad and the indifferent, because everything is of some value. There is always more and more to be said. And soon you will be very happy to be finding out at the Tate Modern, in tremendous, voyeuristic detail, much of what he made, and many of the things that he did as he shuttled between one home and another in order to keep wife and mistress in a balanced state of contentment, and how many pardonable-for-great-art’s-sake duplicities he was guilty of, in the year 1932.

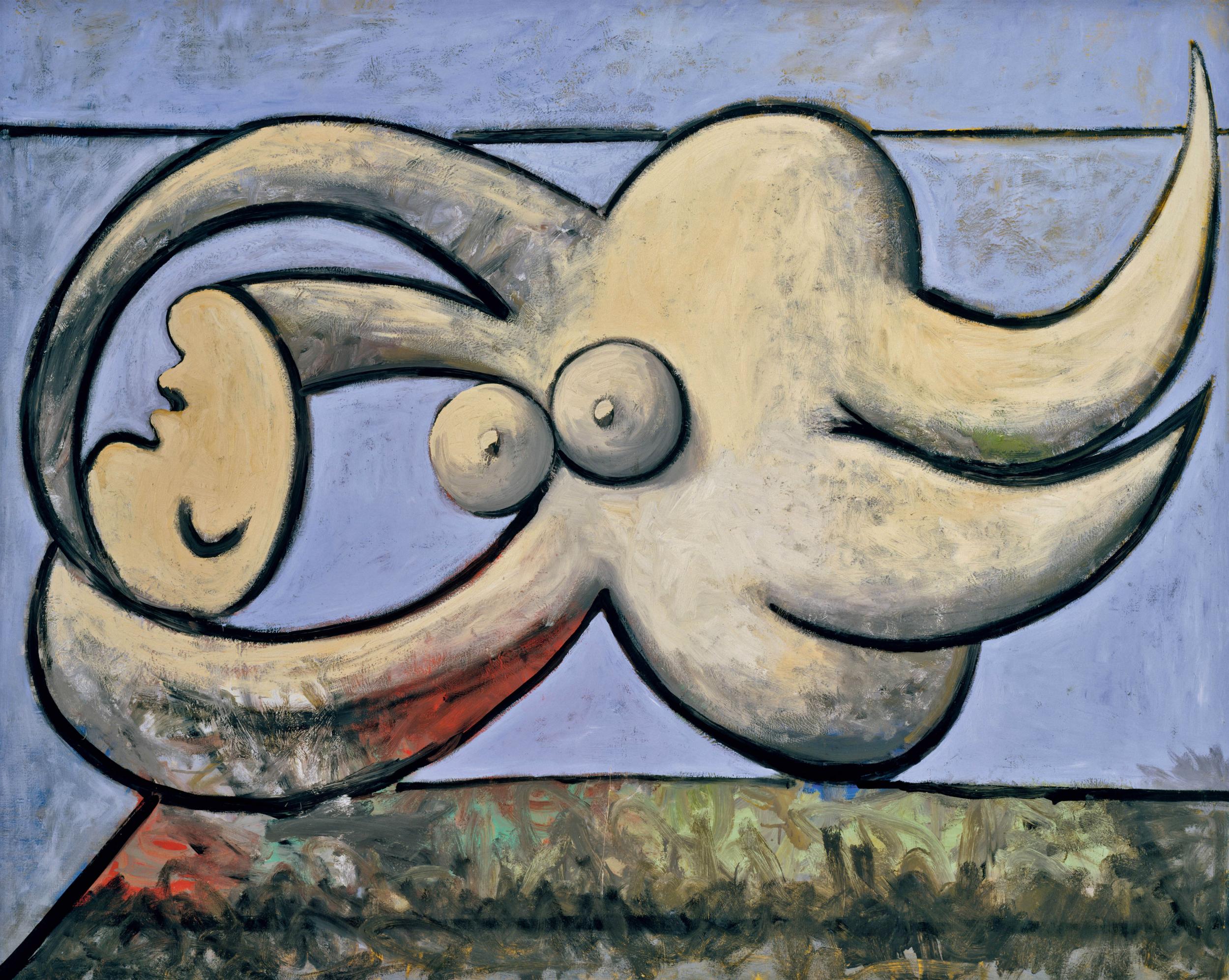

Along with more than 100 paintings, sculptures and drawings, the Tate Modern exhibition will exhibit family photographs to give an insight into his personal life. Three paintings of his lover Marie-Thérèse Walter are to be exhibited for the first time together since they were produced over five days in March 1932.

And if you want to see yet more Picasso, refreshed, amplified and heroicised all over again, you will need to travel no further than the Musée Picasso in the chic Marais district of Paris in March, where a huge exhibition is being devoted to the subject of Guernica, a black and white anti-war painting on canvas, completed by Picasso in June 1937. And what exactly will that exhibition consist of? There will be International Brigade posters. There will be preliminary sketches. There will be commentary. There will be much storytelling and interpretation. There will not, alas, be the painting itself because it is not allowed to travel out of Madrid. So the very subject of the exhibition, that about which it pivots, will be absent. But no one will care much because the spirit of Picasso will be there, won’t it?

The fact is that Picasso is a smoothly and artfully managed global industry, and one of the consequences of this skilful management of Picasso is that old news stays news because the story always has a little bit of something new about it, some detail fresh from the archive perhaps. And many want it to remain so, not least his family and the Fundación Picasso. How fortunate that incalculable monetary value should be so skilfully aligned at last with spiritual values!

Picasso 1932 – Love, Fame, Tragedy, is at Tate Modern from 8 March until 9 September 2018 (tate.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks