Queer British Art at Tate Britain: Is it wrong to group together LGBT art?

Billed as ‘the first major exhibition dedicated to queer British art’, Tate Britain's brand new show, which covers gay art from 1861 to 1967, joins a host of other galleries and museums celebrating the Sexual Offences Act of 1967, that partially decriminalised male homosexuality

Galleries and museums across Britain are marking the 50th anniversary of the Sexual Offences Act 1967, the legislation that partially decriminalised male homosexuality in England and Wales. The National Portrait Gallery recently opened an exhibition exploring London’s gay scene in the 1980s, hot on the heels of its Speak Its Name show; while the British Museum’s Desire Love Identity: Exploring LGBTQ Histories opens in May; in Manchester the People’s History Museum is documenting 200 years of activisim in Never Going Underground: the Fight for LGBT+ Rights; while Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery will showcase how artists responded to decriminalisation in Coming Out: Art and Culture 1967-2017, opening in July.

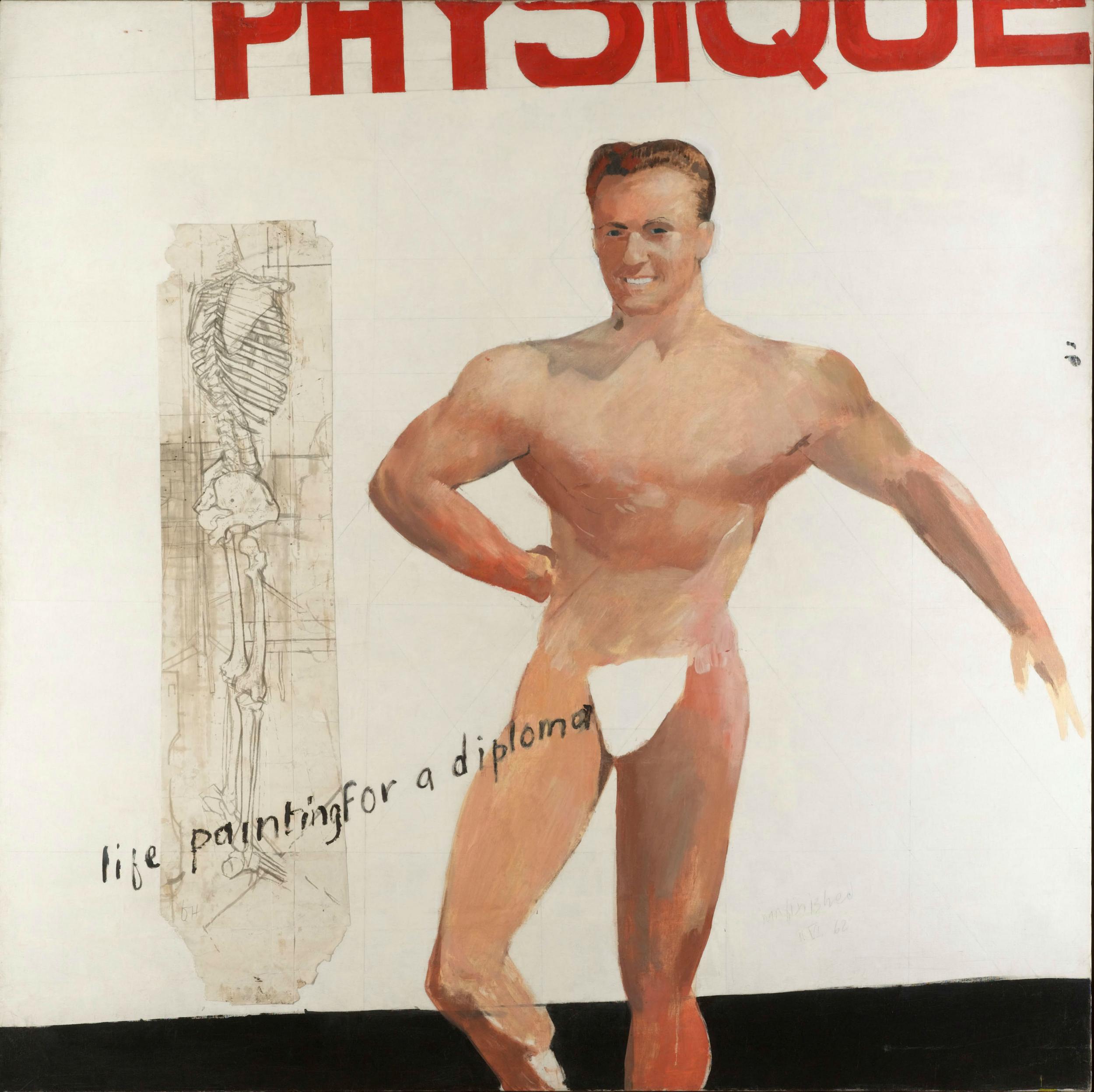

But the biggest of this series of blockbuster exhibitions on the topic is Tate Britain’s Queer British Art 1861-1967, which seeks to place art that reflects, celebrates and reveals the nuances of non-binary, non-heterosexual and gender fluid identities in Britain firmly in the frame. Billed as “the first major exhibition dedicated to queer British art”, it is designed to redress how overlooked, sidelined and forcibly ignored such artworks and artists have been by art history – and to showcase works that give voice, however coded, to these oppressed identities.

Works date from the abolition of the death penalty for sodomy in 1861 to the passing of the Sexual Offences Act just over a century later. Lesbianism wasn’t technically illegal (never mind a widely refuted myth that this is because Queen Victoria “didn’t believe that it existed”), but gay women were nonetheless also unable to live openly without great risk of personal persecution.

But the criticism levelled at these blockbuster shows is that they are drawing lines through genres based on an artists’ sexuality, and doing this arbitrarily, perhaps even insultingly. Writing in The Independent last year, Janet Street Porter accused Tate Britain of “lumping together” LGBT artists, criticising the view of “queer art” as a movement.

“It’s about art, not artists,” says Tate Britain curator Clare Barlow, said in response to Street-Porter’s comments. “Each object in the show provokes really interesting questions about identity. There are some artists who are in same sex relationships whose work doesn’t appear in the show because it doesn’t prompt those questions. The exhibition is the first of its kind. We are absolutely not presenting it as a closed canon. It is the start of a conversation.”

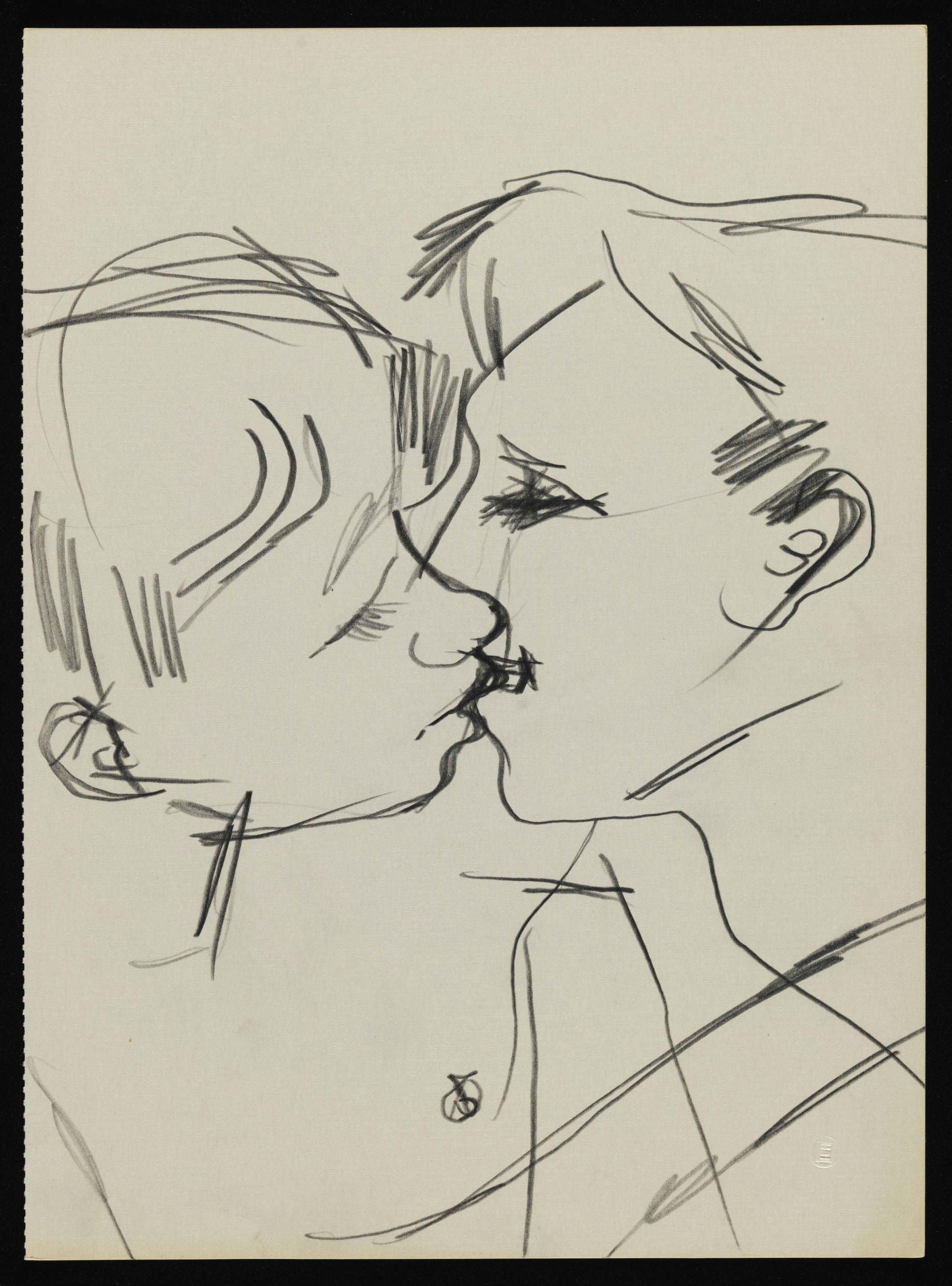

Many of the works set to go on show date from before it was usual to use the words “gay”, “lesbian”, “bisexual” or “trans”. Barlow says: “What’s fascinating about it is the extent to which same sex desire and gender variants are current across art of this period. We are moving from a period of very fluid identity into one where terms identity are beginning to be used.

“There’s just such a range of identifications in the show. It’s very tempting to put the past into boxes: here are the gay men, lesbians, trans artists. But many of these artists so nuanced and complex. They are coming at these explorations without the language that we use today.”

But is this really the first time a major exhibition has looked at gay art as a visual genre through which you can mark the historical and societal shifts in gender identity and understanding? “In the past when LGBT stories have been explored [in galleries] there’s been an emphasis on erotic artworks. But what’s interesting about this, given that it’s a period of oppression, with jail potentially a consequence, is that it feeds into every aspect of these artists’ lives,” says Barlow.

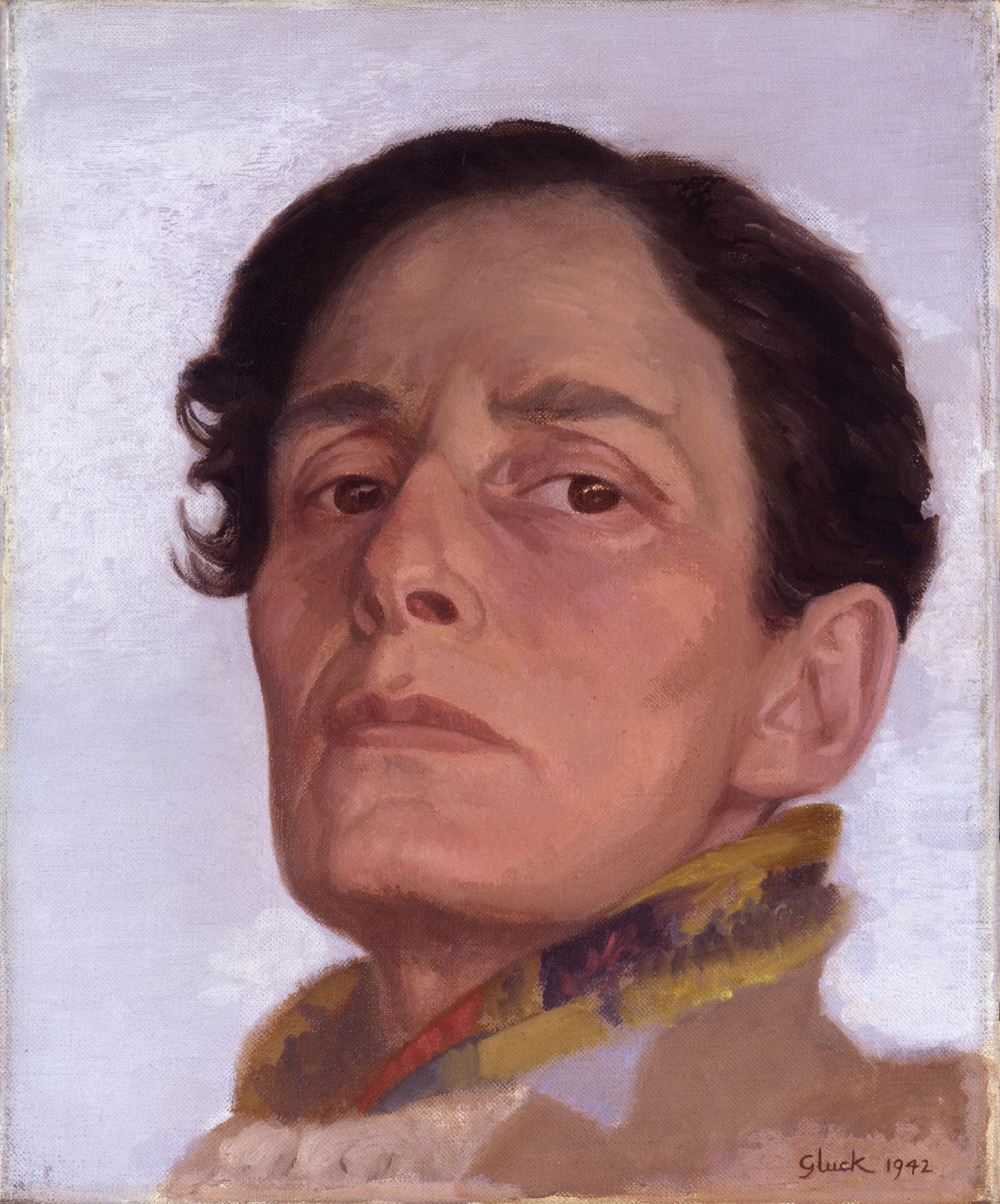

“The exhibition isn’t about ghettoising queer artists it’s about exploring every aspect of their lives. That’s why it was important to me to show a real range of stories. There’s real tragedy but also real joy, failure but also phenomenal success, like Gluck. It’s about celebrating this extraoardinarily diverse, creative experience.” A painting of a vase of flowers by Gluck, who was born Hannah Gluckstein, is one of the star pieces of the show, according to Barlow. “I’m expecting people to think ‘why is a vase of flowers included?’ But if you look at it, [Gluck] painted it at the start of her famous relationship with the society flower arranger Constance Spry.”

Also on display will be a full-length portrait of Oscar Wilde, exhibited alongside the door of his Reading Gaol cell, where he was incarcerated from 1895 to 1897 for gross indecency. Covert images of same-sex desire such as Simeon Solomon’s Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene 1864, will hang alongside homoerotic drawings by Aubrey Beardsley.

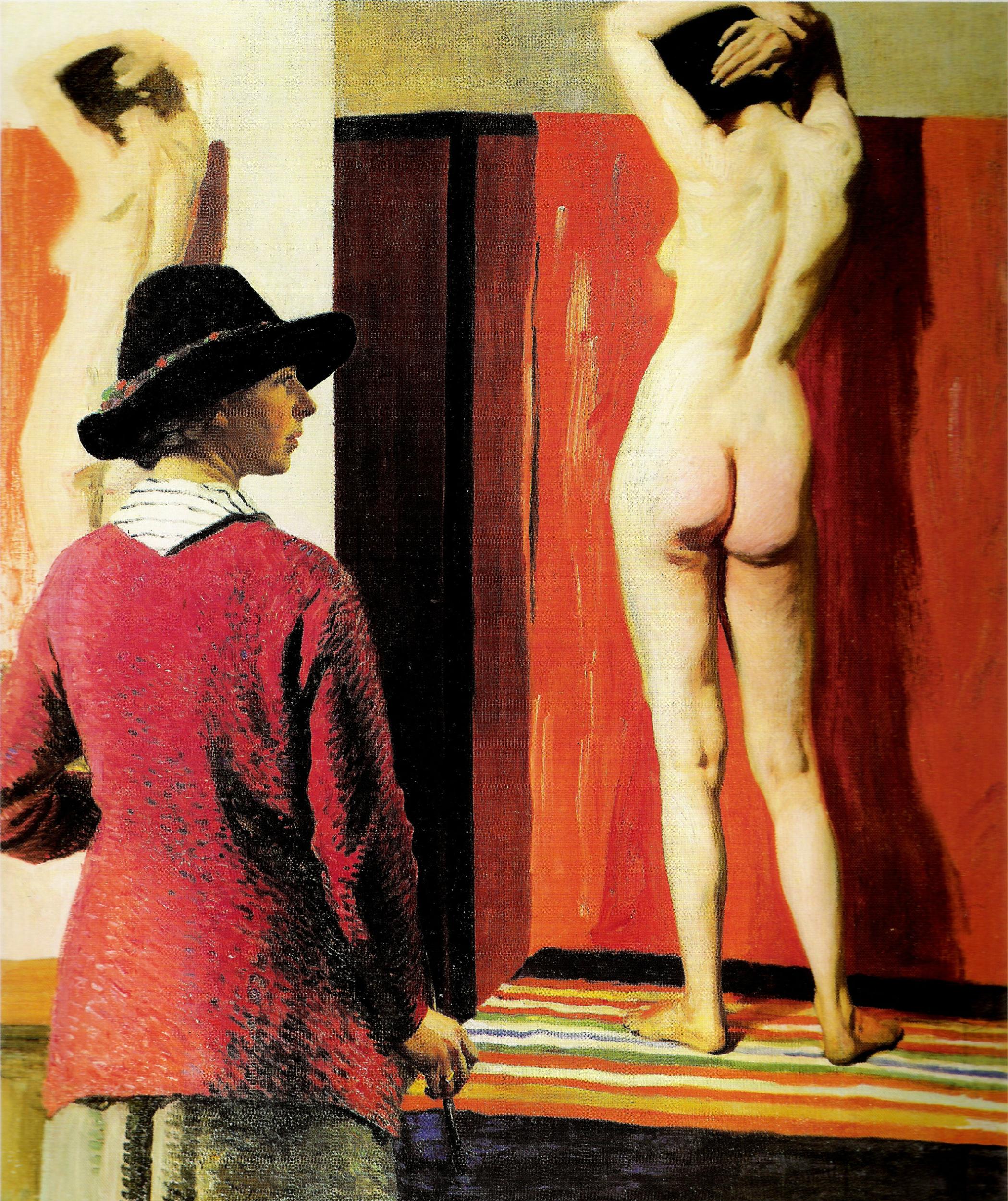

There will also be a room of the exhibition dedicated to art that defies heterosexual “norms” but isn’t by gay or trans artists. Among these is Self Portrait by Laura Knight, which when it was first shown in 1913, shocked the establishment because it showed her, the artist, painting a female nude. The Telegraph’s critic derided it as “vulgar”. Barlow says: “It’s interesting reading [the review today] because the reviewer can’t really get a handle on what it is that he doesn’t like. There’s a real sense of anxiety in his response to that painting. Perhaps because it subverts the traditional hierarchy between the male artist and female nude.”

Barlow emphasises that the show is “very much queer British art not queer British artist” and says she chose to use the word “queer” in the sense that Derek Jarman used it and because “it captures that sense of fear and liberation through creativity”.

Tate Britain's 'Queer British Art 1861-1967' exhibition runs until 1 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks