Sharaku: The mystery man unmasked

In 10 months, Japanese artist Sharaku created prints that became classics – then he vanished. Adrian Hamilton is gripped by an enigma at the Tokyo National Museum

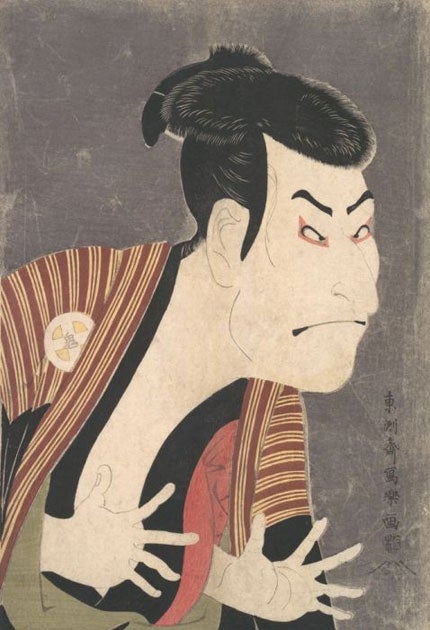

To walk into a room of half-length actor portraits by the 18th-century Japanese woodblock artist, Sharaku, is a totally gripping experience. The faces leap forward, grimacing, laughing, malicious or withdrawn, the eyes staring, the mouths turned down. Never for a moment do you forget that these are portraits of actors playing a role, male or female, But then look harder, and you know that these actors are also real men (for kabuki actors were all male) adopting the masks of their art.

Only Toulouse-Lautrec has this extraordinary gift of depicting acting as individuals (women in his case) putting on a face to the world. But then Lautrec was himself profoundly influenced by Japanese woodblock prints.

Sharaku, the subject of a monumental retrospective that has just opened in Tokyo, lived a hundred years before the Impressionists. Despite his fame today, almost nothing is known about him. He emerged seemingly out of the blue in early 1794, produced a total of 146 known prints within a short 10 months and then just disappeared.

The Japanese call him the "enigmatic ukiyo-e master". But his art is anything but. It is direct, total and, in his earlier works, revolutionary. Look at a collection of Japanese prints of the period, as you can in this exhibition, and you know instantly which are his. The eyes are more assertive, the looks more dramatic and the compositions bolder than anything hat had occurred before or since.

His portraits, produced by an imaginative publisher, came out in four batches to coincide with the seasonal openings of the kabuki theatre. Aside from a few pictures of sumo wrestlers and memorial prints, virtually the entire output under his name was of contemporary actors in their various parts. The style varies between periods, the quality deteriorates as they proceed. And then the output just stops.

That is the enigma that has obsessed art historians. Was he a single artist or, given the differing styles and quality of his work, several people working under a single name? Did he stop working or as, as some others did, continue under a different name? Was his output the genuine creation of a single genius or were others behind it?

The exhibition at the Tokyo National Museum does not claim to provide new answers. But what it has set out to do is to supplement its own holdings of 80 works with borrowings from the US and Europe to show the best available impressions of all but four of his known works and to set them in the context of the portrait and actors prints of his contemporaries and successors.

The curators believe that Toshusai Sharaku was a single figure who'd been a Noh actor, as described in the first written references to him a century and a half ago. And they lean heavily towards the view that much of the "enigma" of his brief period of activity can be explained by his relationship with his publisher, Tsutaya Juzaburo, who had the courage to launch a series of portraits of kabuki actors by a new name in the novel half-length, or oban, form.

Sharaku was unusual in only working for one publisher and Tsutaya's direction would certainly explain how a fresh artist could appear on the scene with what were relatively expensive large prints. It may also have determined why Sharaku changed format and style as other artists and publishers vied for position in the growing market among Kabuki fans for portraits of their heroes. Graphic art can never be separated from commercial imperatives, in any place or period.

Whatever credit is given to Tsutya – a book publisher who also commissioned some of the finest and most famous prints of beauties by Kitagawa Utamaro – what cannot be explained away is the sheer originality and brilliance of Sharaku's work itself. Most people probably know his most famous images – The Actor Otani Oniji III as Edobei, The Actor Ichikawa Ebizo as Takemura Sadanoshin and The Actor Ichikawa Komazo II as Shiga Daishichi – but when you see all 28 of these oban portraits with their grey mica backgrounds you are simply knocked out by the sheer energy and force of his invention.

With the second series of 38 works, the prints change format to full-length osaban figures. The invention is still there, so is the confidence of design, although not perhaps the same portrait realism. While Sharaku is best known for his single portraits, there are some really wonderful double portraits in the second series, and far more of them.

Why the change in format in the second and succeeding periods? It may have been market taste, although the curator, Tazawa Hiroyoshi, suspects it was more likely to have been to do with the reaction of the actors themselves to the first portraits. "We have no evidence," he argues, " but part of the cost of the prints may have been subsidised by the actors and their fans, and they were none too happy about being presented so realistically themselves. If you look at his portraits of onnagata (female impersonators), you're in no doubt that it is man acting the part of a woman, which was not the impression they wanted to give at all."

That, and cost cutting, may help explain the falling off in vigour of the third and smaller fourth periods of Sharaku's work. The museum may be a little too disparaging in describing his final prints as "evoking a sense that Sharaku's richly individualistic life force had been extinguished". The work isn't of the same quality, true. They lack the sense of a real actor behind the pose. But they are not negligible. Put the later prints against other artists of the time and they still come out well.

How to explain Sharaku's subsequent disappearance from the scene? The answer may lie in his relationship with his publisher. Utamaro and others left Tsutya at the same time. But they went on to work for other publishers. Sharaku did not. Perhaps he was just a singular genius who'd said all he wanted or found the growing pressures of market demands and publisher's instructions finally too much.

The important point is that, in those 10 short months of activity, he produced an amazing number of works, several dozen of them real masterpieces. If ever there was an artist deserving the full exhibition treatment it is Sharaku. It was almost exactly a hundred years ago that his name was plucked from the obscurity into which it had fallen among Japanese scholars by a German scholar, Julius Kurth, who produced a seminal work claiming the artist one of the world's three greatest portraits alongside Velázquez and Rembrandt.

Now the Japanese have done him justice in an exhibition that is not just the most comprehensive ever but one that will probably never be repeated. It's opening was delayed by a month because of the earthquake. "We wrote to everyone to say whether they were still happy to lend," says Tazawa Hiroyoshi with feeling, "and I'm glad to say that the British Museum was the first to reply 'yes, absolutely.'" Go if you can, Tokyo needs support at this time of crisis. But if you can't make it, maybe the British Museum, which produced such a great exhibition of Utamaro 15 years ago, could use some of the goodwill it has gained this time to plan its own, albeit smaller, show of this mighty meteor of his art.

Sharaku, Tokyo National Museum ( www.tnm.jp) to 12 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks