'Sicily - Culture and Conquest' at the British Museum: How a little kingdom made a huge multicultural impact

As the British Museum brings the artistic riches of Sicily to show in London, Boyd Tonkin looks at how a stream of overlords, from early Greeks and Arabs to Normans and – eventually – Italians, has left a beautiful if sometimes brutal legacy

Too few people visit La Zisa. This pleasure-palace built in the 1160s by the Norman kings of Sicily sits behind a clumsily landscaped park – until recently, a rubbish-dump – in a scruffy neighbourhood of Palermo. One tourist who did make it was the English artist Lord Leighton, who copied the design of one room for the famous “Arab Hall” in his show-off home in Kensington. With its cascading ceiling decorations in a North African honeycomb motif, mosaic-tiled fountain on the floor and Arabic inscriptions outside, this is an Islamic-style retreat fashioned for a Christian king. La Zisa captures in miniature the multicultural mash-up that made the Norman kingdom of Sicily such a special place. Even its Italian name comes from the Arabic al-Aziz, “the Splendid”: an honorific title for Sicily's King William II, who slipped away from court intrigue to have fun here.

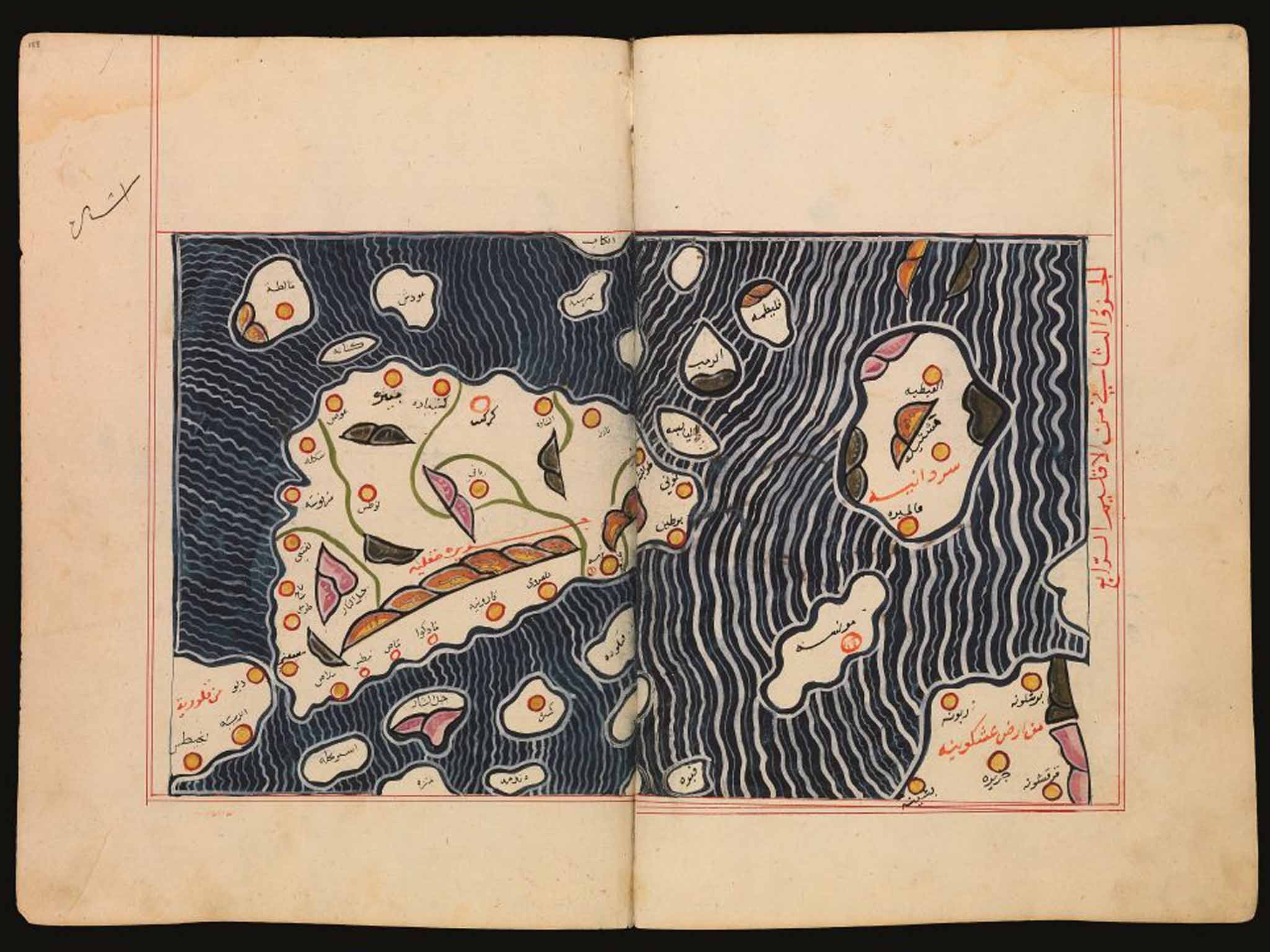

Inside, La Zisa hosts an even more extraordinary proof of diversity as state policy in Europe – more than 850 years ago. One room displays an epitaph for Anna, the mother of a priest who worked at the court of Roger II. A Catholic monarch, crowned in 1130 by the Pope, Roger dressed, conversed, sat and ate in Arab-Muslim fashion. He was the first Norman baron who, after toppling Sicily's Arab governors but cherishing their culture, ruled as an independent king here. And Anna's memorial appears not only in the Latin, Greek and Arabic commonly found in Norman Sicily but also in the Judaeo-Arabic spoken by the island's Jews – a dialect of Arabic, but written in Hebrew script. The date of her death is marked in four calendars: 1149 for Latin Christians, with the equivalent year for Greek Orthodox believers, Muslims and Jews.

The little slab is, as Maddalena De Luca of the Soprintendenza di Palermo remarks while we contemplate it, a sort of “manifesto” for tolerance. Dirk Booms, of the British Museum, adds that, “for the court, it was important to be represented in this way.” The ambitious elite, not some eccentric avant-garde, practised multi-faith pluralism in Norman Sicily.

Soon this 12th-century manifesto for multiculturalism will arrive in London. The exhibition “Sicily: Culture and Conquest” opens at the British Museum next month and it will tell a much richer story than the trinity of clichés trotted out when the BM organised a focus group to elicit views of the island: lemons, beaches and the Mafia. Co-curated by Booms and Peter Higgs, the show will focus on two periods when Sicily led the Med (and beyond), thanks to rulers who encouraged many kinds of people to live and thrive in their domains. As Higgs says, “We've tried to bring pieces from the Sicilian museums that we don't have examples of in London.” From its exquisite ancient statuary and medieval paintings to the kind of precious proof of cross-fertilisation that we witness at La Zisa, the exhibition should redefine Sicily in British eyes and minds.

As well as the Norman period (roughly, from 1060 until 1250), the BM's Sicilian showcase will return to antiquity. Between around 500 and 200BC, the island's booming cities, above all Syracuse and Agrigento, became the envy of the Greek world. On Sicily, colonists from the Greek mainland, from Rhodes and from Crete, met but also fought with local tribes and their rivals the Phoenicians. Eventually, they built a sort of Greek America, seen as bigger, richer and brasher than its Aegean parents. Tramp through the super-sized temple complex in Agrigento and you will see why. Higgs notes that “it's not a melting pot of peoples. Cultures don't get diluted, but from all these influences they create something very new and innovative.”

In company with the show's curatorial duo, I toured Sicily on mild late-February days when ripe lemons and oranges hung heavy on the trees in vast commercial groves, and almond blossom spread like confetti over vividly green hillsides. The island had few minerals and no precious metals but enjoyed an enviable fertility. That made it a prize and catch for foreign potentates, from Phoenicians and Greeks to Romans, Arabs, Normans, Germans, Spanish and (finally) mainland Italian overlords. “Anyone settling here quite quickly set up an agricultural system that would produce enough material to trade with, not just for their own consumption,” says Higgs.

The Muslims, who arrived after AD827 – not only an Arab elite, but Berbers and Andalusians too – imported oranges, lemons, dates and sugar cane. They also introduced Europe to pasta. Before them, the Greeks had cultivated the sort of produce that the hillside estate at Agrigento now grows again in the shadow of its 2,400-year old-temples: olives, honey, cheese, wine. Director Giuseppe Parello and his team have reintroduced an ancient species of black bee, and a vintage breed of goat. We sample a classical buffet in the shadow of the floodlit temples of Juno and Concord. It's all delicious. As for the Romans, who finished their conquest around 210BC, they carpeted Sicily with wheat and used it as a breadbasket until Cleopatra kissed her asp and Egypt took over as the empire's granary. No wonder you eat so well here.

Yet this lavish fertility, commemorated in local cults of the earth goddesses Demeter and Persephone, bestowed its own kind of “resource curse”. As Booms says, “It's a theme throughout Sicilian history that foreigners come in, exploit what they can, and then leave.” The BM's displays won't need to investigate the Mafia and its clannish forerunners. However, that tradition of rural brigandage reflects a history of absentee masters who harvested profit from their lands but outsourced control to thuggish enforcers. Maltreated and misgoverned, Sicilians erupted almost as often as Mount Etna – which dominates the east coast around Catania. In the dead centre of the island looms the sinister-looking hilltop settlement of Enna. Here, in 136BC, a great slave revolt set up its HQ. It took four years for Rome to starve the rebels out.

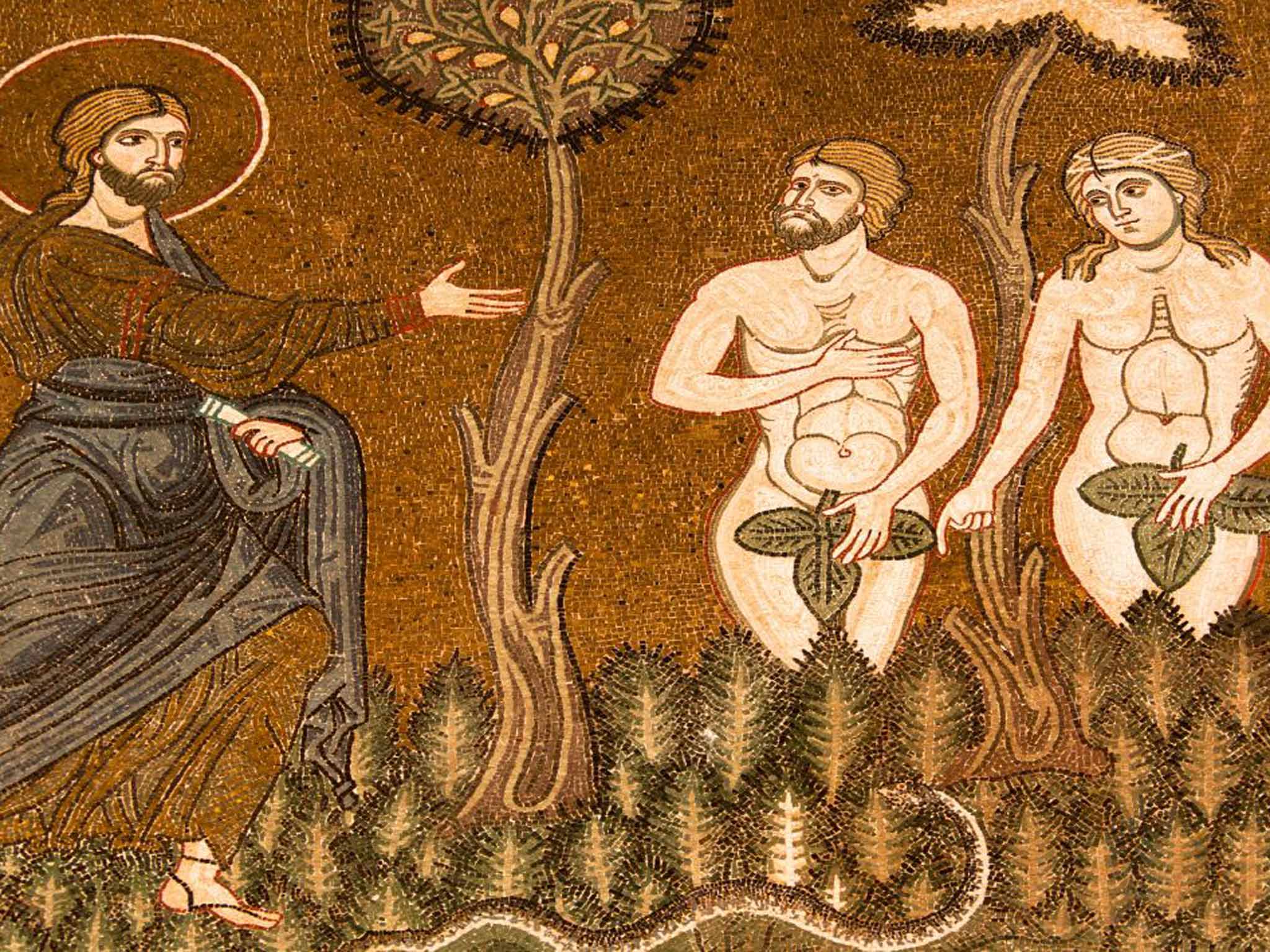

Greek tyrants in Syracuse or Norman kings in Palermo did not invariably govern well. All wished to make a spectacle of their wealth and power: the sort of magnificence you experience both at Agrigento, and beneath the golden blaze of the mosaics that fill the cathedral of Monreale outside Palermo. Still, these rulers cared enough to live above the shop. And they invited the brightest and best to buttress their authority with cutting-edge science, art and architecture.

Pride nurtured a culture of openness and curiosity. In Syracuse, where we gape at the 200m-long foundations of the ancient world's biggest sacrificial altar, Archimedes calculated, designed and theorised on behalf of the benevolent king Hieron II. He had his “Eureka!” moment here. In Palermo, Roger II and his grandson William II hired Greek mosaicists from Constantinople, Arab philosophers and artisans from Egypt and present-day Tunisia, carvers and masons from mainland Italy. All could find a niche and thrive.

As Booms explains as we marvel at the riot of Bible stories on the walls of Monreale, “The Norman kings wanted to measure up to the empires around them. They wanted to be the equal of the Pope in Rome, the Caliph in Egypt, the Byzantine emperor.” Roger II set out to gather top performers from around the Med – whatever their faith – into this “enlightened kingdom”. Beneath the mosaics, our guide Father Nicola Gaglio emphasises that a common style – a “Meditteranean koine” – united artisans and architects from east and west of the great sea. Their arts called for tolerance and peace. For Booms, Roger saw “that the way to do that was to unite peoples rather than divide them.” It's notable how often the idea of paradise recurs on Sicily. Muslim settlers and visitors found in its orchards, groves and gardens the abodes of earthly bliss. Norman lords adopted the notion. In the royal palace in Palermo, the secular mosaics that adorn King Roger's Hall portray beasts both domestic and exotic amid palm trees: from rabbits and peacocks to lions and leopards. Yes, these creatures often had a symbolic or heraldic meaning. But the mosaics also depict the flesh-and-blood menageries that the kings kept in their lush parks.

In Syracuse, we had strolled through gardens in a valley next to the Greek theatre: a favourite spot for walkers, also known as “Paradise”. Surrounded by orange and lemon trees groaning with the weight of plump ripe fruit, one can see why. Yet this lovely corner occupies part of vast ancient quarry that tells another story. In 415-413BC , Athens, which resented the prestige of Syracuse, launched a doomed campaign against the city, and it ended in tears – Athenian tears. “This was their last-ditch bid for an empire,” explains Higgs. “They were entirely obliterated.” Athenian prisoners toiled in the quarries here. Worked beyond endurance, they died in their droves. The historian Thucydides describes the captives “tormented by hunger and thirst”, freezing in cold or wilting in heat in this “hollow place” with a “small compass”. Inevitably, “the dead were piled up on one another”.

In Sicily, paradise could lie very close to hell. However sophisticated their cities, tyrants such as Dionysus I picked up a name for brutality across the ancient world. Did they merit it? Part of this bad rep comes down to hostile propaganda, Higgs believes. But not all: “There's no smoke without fire. I'm sure they were pretty cruel.” Not even the Norman kings presided over unimpeded sweetness and light. The craftsmen from Fatimid Egypt who (probably) carved the ornate roof of the Capella Palatina in Palermo could look forward to respect and protection. However, outside elite circles, they would not mix much. Under the Normans, especially Roger II, the island was itself a kind of mosaic – not an amalgam – but that mosaic shone brightly. Palermo art historian Gaetano Bongiovanni sums up its later renown in the peaceful cloister garden of San Giovanni degli Eremiti, a Norman church topped by a much-sketched North African-style dome. “It was the good reign. It was the successful reign. It was when Sicily was important.”

“Sicily was a place of tolerance,” says Booms, “but only at court was it a place of integration.” When Ibn Jubayr, a keen-eyed Muslim traveller from Spain, came to Palermo in 1184, he noted that his co-religionists lived “in their own suburbs… apart from the Christians. The markets are full of them: they are the merchants of the place.” At court, they were also the scientists, scholars, chefs and concubines. Ibn Jubayr admiringly writes that the Muslim ladies in William II's harem managed to convert their Christian sisters to the one true faith.

This co-existence could prove fragile. Uprisings against the Normans – as in 1161 – might trigger pogroms. Booms sums up the downside of Sicily's elite-directed tolerance: “When the power of the king fell away, everyone who wasn't a Christian was marginalised.” Paradise-by-decree did not last. By the late 13th century, after the death of the Islamophile king (and Holy Roman Emperor) Frederick II and a brief, inglorious period of French rule, absentee Spanish masters pressed the island back into the monolithic mould of Catholic observance. In time, they reduced it to a stagnant provincial backwater. Byzantine mosaics still glittered on church walls whose columns bore inscriptions in Arabic. But Sicily's golden age of pluralism had passed.

Might it revive? Almost every week, those frail, overcrowded craft that manage to avoid shipwreck deposit migrants on the small island of Lampedusa, off Sicily's southern coast. Many of these refugees from strife and poverty in the Middle East and Africa move through Sicily on their way north. Others come ashore at different ports – Palermo included. In the warren-like back-streets of the city today, you still hear Arabic alongside other tongues of Africa and Asia.

Tucked away in the narrow streets of Ballaro, a short walk from the tourist hot-spots of Palermo, a social-services centre attached to the church of Santa Chiara offers practical, legal and medical help to recent migrants. Nearby, the Jesuit Refugee Service provides similar assistance at its Centro Astalli. Opposite Santa Chiara stands the city's Senegalese Association. Close by, the Bismillah mini-market sells halal food. Bismillah: “In the name of God,” the opening words of the Koran. Roger II and all his courtiers would have known that.

I remember that, for his last pre-retirement acquisition as director, Neil MacGregor obtained for the British Museum the “Cross of Lampedusa”. Made by local carpenter Francesco Tuccio, it was fashioned from the timbers of a migrant boat that had caught fire and sunk off Lampedusa in October 2013. Around 350 people lost their lives. Sicily's epic history as an island of welcome, of contact – but of conflict too – has opened a new chapter.

Perhaps some virtual museum of the future will tell our descendants how this latest encounter ends. Meanwhile, some Sicilian artists have already begun to shape this new story. Take a traditional entertainment, the island's puppet theatres' pantomime-style battles between “Saracen” knights and their Christian foes: a clash of civilisations, if you like, but chiefly an excuse for farce, fun and merriment. At his pocket-sized puppet theatre in central Palermo, Mimmo Cuticchio has carried on the family trade since 1973. But he gives these folkloric strings a contemporary twist. For a start, the show that we see on a Sunday evening – with its prancing, sword-fighting and romancing human and animal figures – has Christian and Muslim knights working in consort rather than just slicing one another into salami.

Later, in a workshop filled with his uncannily expressive creations, Cuticchio outlines the modern plots he devises for his metre-high casts. They tell stories for today, sometimes about the triumph of love over bigotry. “Love,” he insists, “has nothing to do with religion.” In a city that once more hosts incomers from Muslim domains, he has produced a puppet Aladdin for schoolchildren.

As Sicily changes, so does its art. Just as it always has. “Although it's a tradition,” the maestro says, “it's always evolving. There's no end point.”

'Sicily: Culture and Conquest' runs at the British Museum, London WC1, from 21 April to 14 August. Exhibition sponsored by Julius Baer in collaboration with Regione Siciliana

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks