Sigmar Polke, Tate Modern, preview: Prepare to be baffled and exhilarated

We fly to New York to get a flavour of the Tate's autumn blockbuster, a survey of the German maverick and his dizzying array of styles, from hand-done dot paintings to hectically psychedelic collages

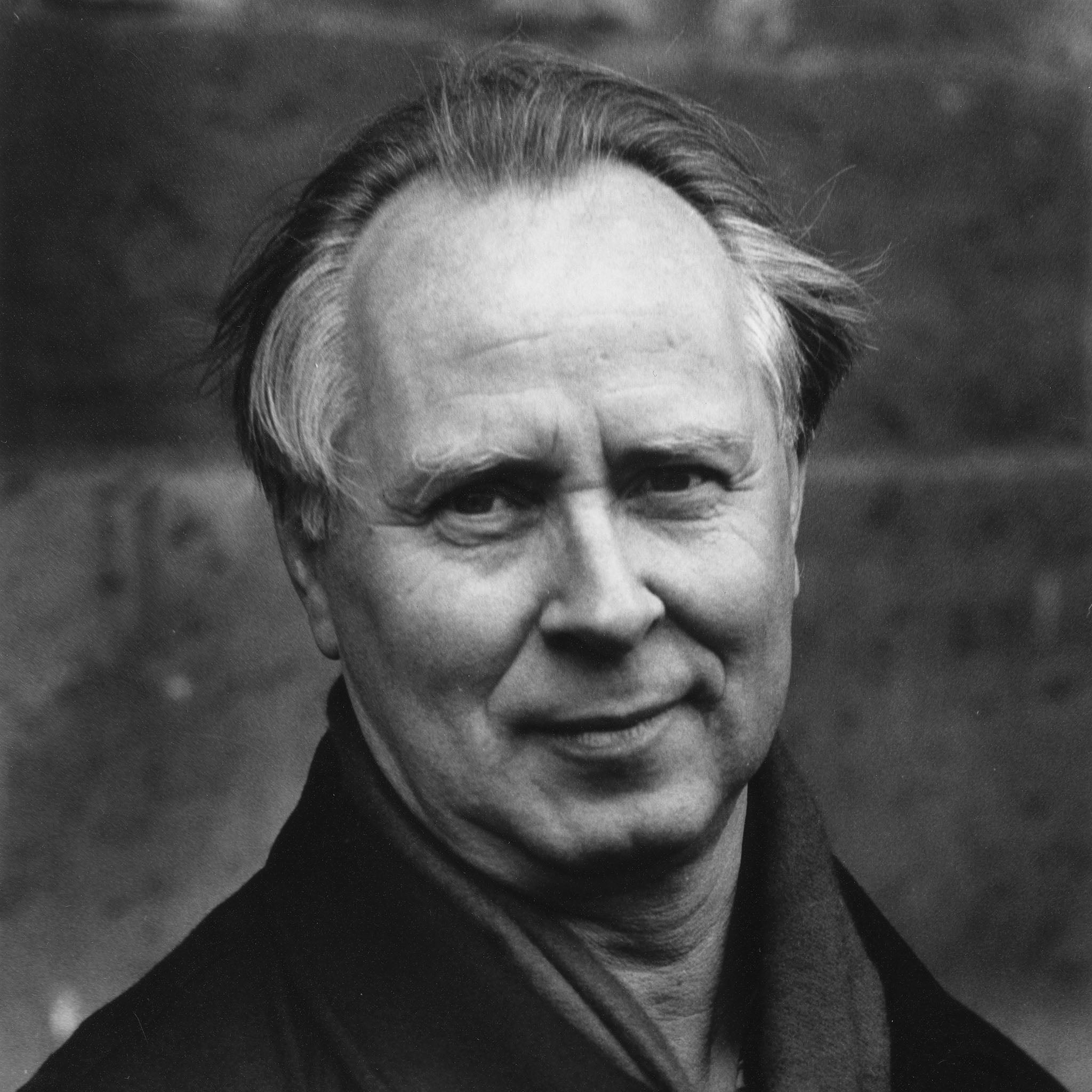

German artist Sigmar Polke’s work has often been understood in terms of alchemy; the curators of a vast retrospective coming to Tate Modern next month from New York’s Museum of Modern Art take the reverse view.

“Gold seems to be turned into shit,” co-curator Mark Godfrey tells me, matter-of-factly.

“We see [his work] more in terms of contamination and poison,” he continues. “It’s not really about transformation to raise things up – almost everything becomes toxic.” Alibis: Sigmar Polke 1963–2010, which I saw in New York, certainly brings into focus the outlandish range of substances Polke used. Both material and ingestible, that is – he had a seriously druggy period in the 1970s.

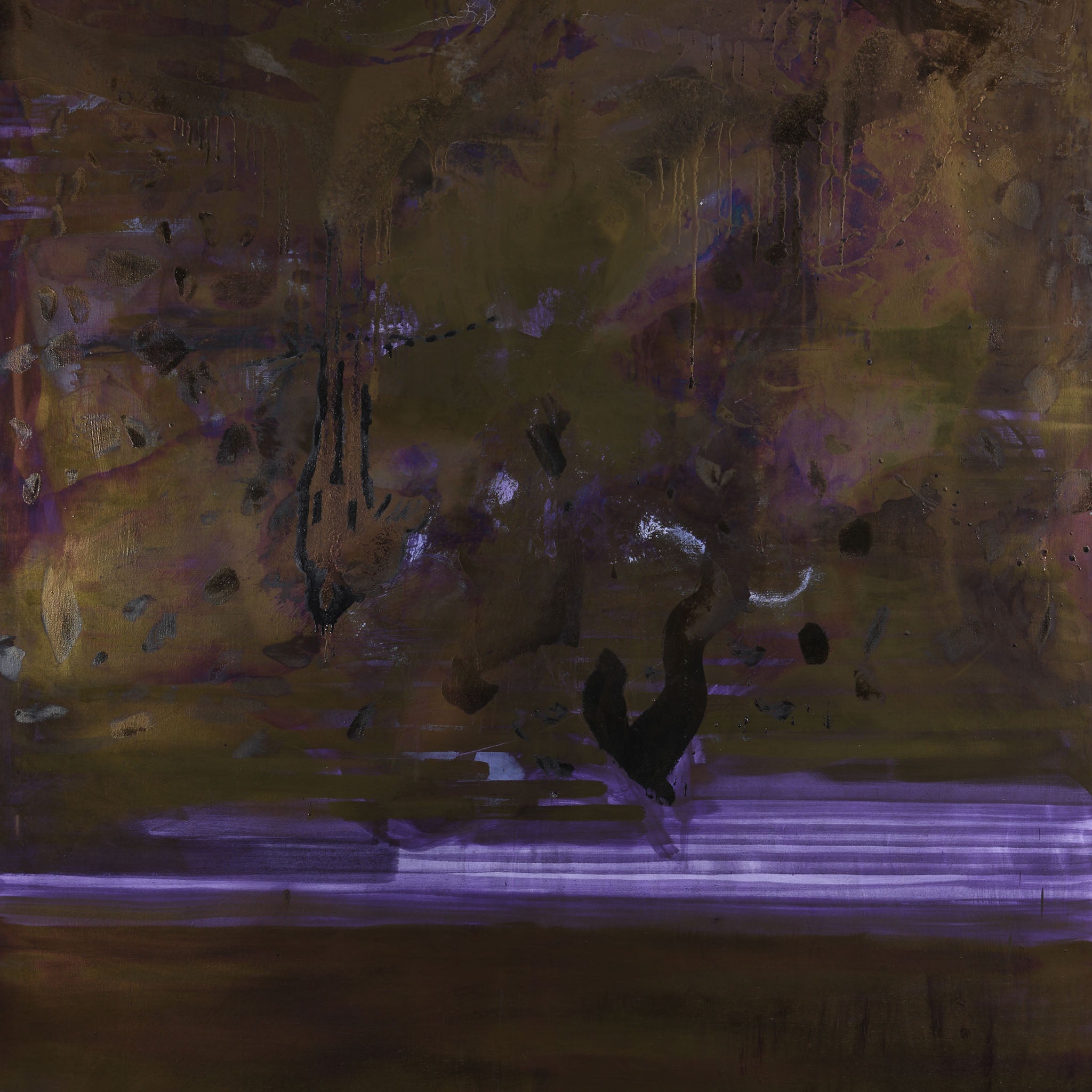

Paintings are made with everything from snail ooze to meteor dust, uranium to smoke. Often, these are used to beautiful effect – a 1982 triptych, Negative Value, consists of large, sumptuous canvasses of pooled purple pigment and an oxidising metal coating. But he renders beauty unstable, in this case burnishing the canvases so that they glow an obstructive bronze or green depending on where you stand. Tarnished as much as burnished, perhaps.

And his work is as unstable in meaning as it is in medium. He worked with MoMA associate director Kathy Halbreich on the show before his death from cancer in 2010; she describes him as “a very strong person, but ... elfin and mischievous”. That’s not surprising, looking at the show; one of the largest ever displayed at MoMA, the 265 works seem to bounce around the gallery: bizarre, bright, baffling.

Walking through the show, you whip through artistic styles. At the beginning, there’s his work under the banner of Capitalist Realism, the art movement he launched in early 1960s which spliced East German Socialist Realism with American Pop Art, and paintings using hand-done raster dots recreating commercial mass-printing (like a wobbly Lichtenstein); in the middle, there are travel photographs, film and hectically psychedelic collages, while the closing rooms are dominated by his later abstract large-scale works. Throughout, Polke both uses and mocks a huge range of sources and cultures: kitsch, advertising imagery, newsprint, conceptual art, abstract art, documentary photography, computer technology, psychedelia, exoticism, and the paranormal. It is, frankly, as exhausting as it is exhilarating.

This is the first time such a vast and varied selection of Polke’s work has been displayed together; the Tate’s show will be slightly smaller, with 200 works. In the past, curators have tended to parcel him up just as a post-war painter: “It was easier to sell Polke to the world in the Eighties as one of the German painters, same as Gerhard Richter, Anselm Kiefer, Georg Baselitz,” suggests Godfrey. But Alibis’ approach has been rapturously received in America, The New Yorker suggesting it may be “the most important” museum show of this century, crediting his trashing of conventions with revitalising the very medium of painting, and delivering a powerful call to young artists to think harder, wider, deeper about their “ethical and aesthetic” practice.

And in bringing together this cacophony of media and modes, the curators may finally have found Polke’s point. “What you see is stylistic inconsistency, [but] intellectual or philosophical coherence,” says Halbreich. Which is…? “[An emphasis on] the instability of vision; the fluctuation of any one truth; the scepticism about any authority … when you see his career you see there is an urgency, a lust, a necessity to keep trying.” Even the point is un-pin-downable.

Although Polke resisted simple interpretations, it’s impossible not to read his biography into his work – given that he was born in 1941 into fascism, and became an artist making deliberately unfixable work in the aftermath.

Born in Silesia, his family fled in 1945 after the region was taken back by Poland after the war, and after living in Communist East Germany, they fled again to the west German city of Dusseldorf in 1953.

Polke’s father was an architect who, it is thought, worked on military facilities for the Nazis. Polke, throughout his career, has confronted the regime’s legacy. “What Polke really makes us look at is the ultimate German alibi – ‘I didn’t see anything’, the silence of the fathers,” says Halbreich, adding that the artist was also concerned with “the silence of his own generation”. There are swirls of swastikas in both small notebooks and epic paintings – a banned image in Germany, but one he wanted his country to face. At an early show in Dusseldorf, he snuck into the gallery the night before it opened and installed a slide show of Nazi leaders under the slogan “art will make you free”. Art, he suggests, cannot save us now, and following the Holocaust, nothing can ever be pure again. After all, it was the seeking of purity that led to such atrocities.

Brought together for the first time in this retrospective are a series of large paintings of watchtowers from 1984. “It is a banal image – you see them to this day in the German landscape, hunters use them,” explains Halbreich. “But they were also found along the East-West border. And, of course, they surrounded the concentration camps.” She points out how Polke used silver bromide, a light-sensitive photographic chemical, which would cause the image to blacken over time so that “that which was supposed to illuminate would actually darken. He is looking at this idea of repression of memory, of what can we make after that apocalyptic vision.

“The one thing we know is that we can continue to experiment, we can continue to be alive,” says Halbreich. And here, perhaps, is Polke’s moral centre, after all. “If he believed in anything, it was this investment in restless experimentation – to keep trying.”

Such instability continues right through to one of his final works in 2009, a window for a cathedral in Zurich, in which he recreated the classic optical illusion, Rubin’s Vase, in which the outline of two faces make a vase. Even in a place of faith, he placed uncertainty. “It’s not simply a ‘fuck you’ [to religion], it’s really a profound need to re-see and re-think the givens of the world,” insists Halbreich.

That illusion also uses the optical trickery of negative space – which brings us back to that Negative Value triptych. As a title, it references his destabilising of meaning, his destructive urge, his turning everything to shit. Yet there’s value there. It brings to mind Keats’ coinage, “Negative Capability”, which the poet famously defined as “when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” That may serve as a guide for appreciating Polke: forget pure beauty; revel in the experimentation; never let the bastards pin you down.

‘Alibis’ is at Tate Modern, 9 Oct to 8 Feb; tate.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks