The World Goes Pop at Tate Modern: How pop art was used as dissent

Tate Modern's autumn show changes 'the traditional story of Pop Art'

In his 1975 autobiography Andy Warhol wrote: "The most beautiful thing in Tokyo is McDonald's. The most beautiful thing in Stockholm is McDonald's. The most beautiful thing in Florence is McDonald's. Peking and Moscow don't have anything beautiful yet." Perhaps he was being ironic, which is worse.

I've never been taken by the mystique of Warhol, the most famous exponent of Pop Art. Rather, I think the rage of the late art critic Robert Hughes in his 2008 documentary The Mona Lisa Curse was righteous. Hughes hated the cult of wealth and emptiness which is Warhol's legacy to the art world. Thankfully, there are no soup tins and Marilyns in the new exhibition, The World Goes Pop, at Tate Modern, London, though Warhol's shadow is everywhere.

The intentions of the exhibition are good: rather than focus on the British and American tradition, the curators have searched hard for lesser-known artists from around the world who made Pop Art in the Sixties and Seventies as a form of dissent against systems of power: military dictatorships in Latin America, the war in Vietnam, the oppression of women. The aim here is not to idealise consumerism, but to "explode the traditional story of Pop Art". Unfortunately, the exhibition is a mess.

The term Pop Art was coined in Britain in the 1950s. The British artist Richard Hamilton described it as "Popular (designed for a mass audience); Transient (short-term solution); Expendable (easily forgotten); Low Cost; Mass Produced; Young (aimed at Youth); Witty; Sexy; Gimmicky; Glamorous; and Big Business".

Few works by American artists are included in the exhibition, but the works by international artists often use the visual language of American pop culture to critique American political and cultural domination. In this way, America remains the focus. A lot of the work feels too much in thrall to the charisma of the bully.

The walls are painted in lurid colours: bubble-gum pink and sour yellow. The aesthetic is often migraine-inducing, a frenzied mix of high and low culture, with hysterical montages that rail against their own raw material: the mass media. It's great that so much feminist art is included, but a lot of it is not very good. This is a shame: the exhibition could offer an important archive of a period of intense female creativity.

A whole room is dedicated to the Czech artist Jana Želibská's installation, Kandarya-Mahadeva (1969), named after a Hindu temple in India. The walls are adorned with huge, white, female figures and garlands of flowers. The genitals of the figures are covered by mirrors in which the viewer can see herself. It is a mystical homage to female eroticism. This is not a good use of space; it feels dated.

The novelist Angela Carter wrote on this tendency within the women's movement: "If women allow themselves to be consoled for their culturally determined lack of access to the modes of intellectual debate by the invocation of hypothetical great goddesses, they are simply flattering themselves into submission (a technique often used on them by men)."

More successful is Consumer Art (1972-75), a film fragment by the Polish artist Natalia LL, which plays on a loop. It shows a close-up of a beautiful young blonde woman seemingly experiencing sexual ecstasy as a white foamy liquid dribbles out of her mouth. The film is a parody of the use of pornographic imagery in advertising, which gained force alongside the sexual revolution of the time. But it is not just absurd; it is magnetic. In this way, the artist ensnares the viewer in a trap of desire. She makes you want what she is mocking.

Some of the best works in the exhibition come from Spain. The Punishment (1969) by Rafael Canogar is simple and stark. It is a sculpture of a man in a black suit who has fallen at the feet of an authority figure. The latter is no more than a dark shadow on wood, truncheon raised. The fallen man's face is hidden. Perhaps the title of the work refers to the possible consequences of making the artwork itself. Franco had not yet died. This is art with much at stake.

A painting which hints at the horror beneath the surface of Franco's Spain is Isabel Oliver's Happy Reunion (1970-3). It shows a scene in a middle-class living-room: women are laughing and talking. It's polite. But outside the window, a Dali-esque landscape of melting forms and swirling colour can be seen; it appears a psychosis, held at a distance. The image is undermined by the inclusion of a giraffe on fire. This makes the whole seem tacky.

Another striking work from Spain is Concentration or Quantity becomes Quality (1966) by the collective Equipo Crónica. The series of nine paintings shows a transformation from isolation to collective strength. In the first painting, a few solitary individuals are surrounded by vast grey space. Over the course of the series, the space fills up with people. In the last painting, there is a dense crowd. This work, too, was made in the last decade of the Franco regime: at that time, it perhaps reflected hope, rather than reality.

One of the worst paintings is Big Tears For Two (1963) by the Icelandic artist Erró. It shows a cartoon version of Picasso's painting The Weeping Woman (1937) alongside a Disney cartoon of a weeping train. It is awful. The implication is that high art and low art have been levelled; one is no more profound than the other. Both expressions of grief are equally valid. Except that they are not.

Picasso's painting conveyed the pain of a woman who was living through the Spanish Civil War. Her tears were representative of all those who had lost their loved ones during the fight against fascism. The crying cartoon train is an aberration in this context. It is offensively facile. The painting is quite hateful.

Yet Erró also made the American Interior series (1968), some of the most affecting anti-war images in the exhibition. These paintings on fabric show calm American suburban homes invaded by Viet Cong soldiers. They articulated a primal fear of American society, and reversed the reality: American soldiers were invading the homes of the Vietnamese at the time.

Some of the best works use graphic design in the service of activism. The French artist Gérard Fromanger's Album the Red (1968-70) includes an image of a "bleeding" French flag. The red stripe drips into the white and the blue. It symbolises the wounding of the French establishment in the era of May 1968. Another imaginative protest work is The Red Coat (1969) by the French artist Nicola L. Made of bright red vinyl, this vast, tent-like coat can be worn by eleven people at once. They share a "collective skin".

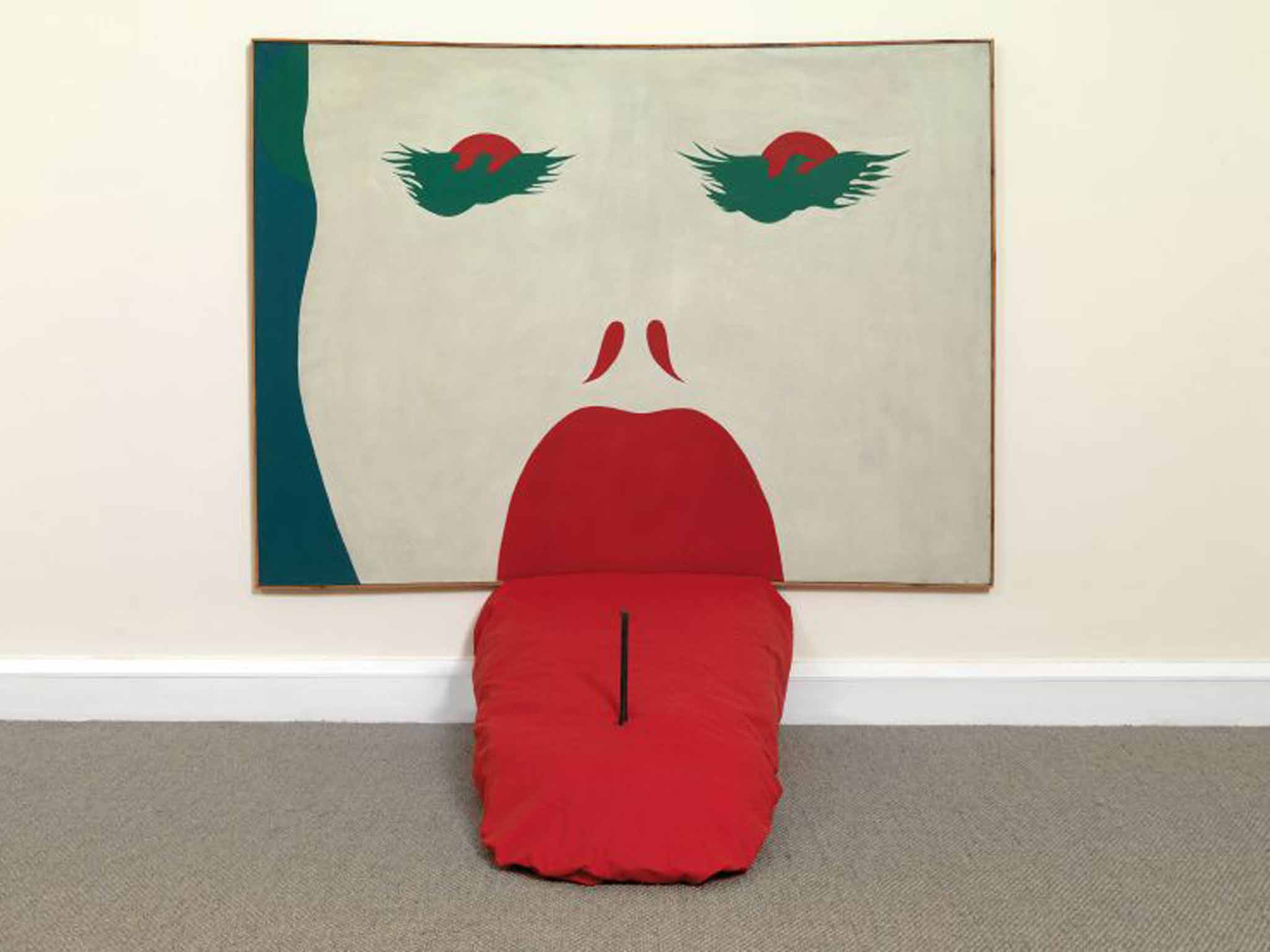

Several feminist works seem ripostes to the British artist Allen Jones's female furniture, which caused outrage at the time because it showed women in positions of extreme submissiveness. Woman Sofa (1968) by Nicola L is a silver vinyl assemblage of female limbs, designed to be sat on. Whereas Jones's fibre‑glass female dummies on all fours were grotesque but stylish works of art, Woman Sofa is just ugly. Perhaps ugliness here is a political principle.

Man Chair (1971) by the Czech artist Ruth Francken is a chair in the shape of a headless man. It is sleek and white and elegant, but it does not point to a new dawn of equality. Rather, it reverses the old power dynamic of master/slave. Mattress (1962) by the Argentinian artist Marta Minujín is simply a dirty old striped mattress; it shouldn't have been included in the exhibition.

While much of Pop Art rejected the idea of "good taste" as elitist, good taste is badly needed in this exhibition. Too many of these works are nostalgic at best.

Tate Modern, London, 17 September to 24 January (www.tate.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks