Artist Vicken Parsons interview: My husband Antony Gormley and I are each other's harshest critics

There’s an old cliché of the male artist slaving away, neglecting his wife and children, but what’s it like when a couple decide to collaborate?

Art history tells us a lot about the role of the wives and lovers of famous male artists: they are the muses, the beautiful faces that stare out of masterpieces, the stories of heartbreak, loss or unhappy marriage that feed the myth and legend around an artist. The stereotype of the obsessive creative genius, the artistic temperament, feeds the idea that brilliant artists need to be supported, cared for even, by the women in their lives.

But what of the wives and lovers who are artists in their own right? Not many women artists have had careers or reputations which eclipsed their partners’; although Barbara Hepworth, Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keeffe arguably did. When two creative people are in a relationship they cannot help but shape and influence each other’s work – sometimes in brilliant, nurturing ways (think Sir Anthony Caro and Sheila Girling); and sometimes to the detriment of one or both of their capabilities (think Camille Claudel who accused Auguste Rodin of stealing her ideas; or talented photographer Dora Maar who is mostly remembered as her lover Pablo Picasso’s The Weeping Woman).

Creativity, after all, needs space. Famously the abstract expressionist Lee Krasner, who was married to Jackson Pollock, believed his talent to be greater than her own. So much so, that despite being the more established name when they got together, her work became smaller and smaller as his grew in scale. They worked together in a great barn at their home in Long Island. She had formal training and he didn’t. She taught the great American artist plenty technically, but she also made space for him, reducing her own output, possibly to accommodate his.

Vicken Parsons, the artist and wife of one of the UK’s best known artists, Antony Gormley, is having her biggest solo show Iris at the Alan Cristea gallery later this month. Her bold, abstract, architectural works have been compared to Francis Bacon and Mondrian’s. She is critically very well received and has had solo shows at Tate St Ives, pieces exhibited at the Whitechapel Gallery in London and is included in major collections. Parson’s paintings are small in scale, perhaps inviting a direct comparison with Krasner, while Gormley’s sculptures, not to mention the 20 metre tall Angel of the North, can be very large indeed.

The couple met while they were studying at at Slade and have three children together. Like many of the artist couples mentioned above they are collaborators as well as husband and wife, having made Bed together (the now famous Tate-owned sculpture made from slices of Mother’s Pride) soon after they met in 1979. She has also worked on the many casts Antony has made of his own body. After all, how could he be expected to make a full body cast without help?

“People often say it must be so hard to be married to another artist but I can’t imagine being married to someone who is not an artist,” says Parsons. “As a couple of artists we have a common purpose and there are few considerations, family being the main one, that either of us would put ahead of making art.”

Bed was first shown at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1981. Parsons wrote of it: “I didn't feel I needed crediting. It was Antony's idea, although we developed the techniques together. As an artist, I always want to keep my identity separate, even though we have done a lot of collaborative work.”

She admits that both she and Gormley are “each other’s harshest critics which is not fun”, but for the most part she says it is useful to talk to him about her work. Their children and financial situation decades ago meant that for a while Parson’s career took a back seat out of necessity.

“In the early days, in fact for a long time, I used to help Antony as an assistant, not as a collaborator,” she says. “We had three young kids, no money, it was a very practical thing to do in order to help the family finances as well as a way of being close to him and his creativity. I never stopped painting but it’s so much easier now, the kids are grown up and Antony has other assistants.”

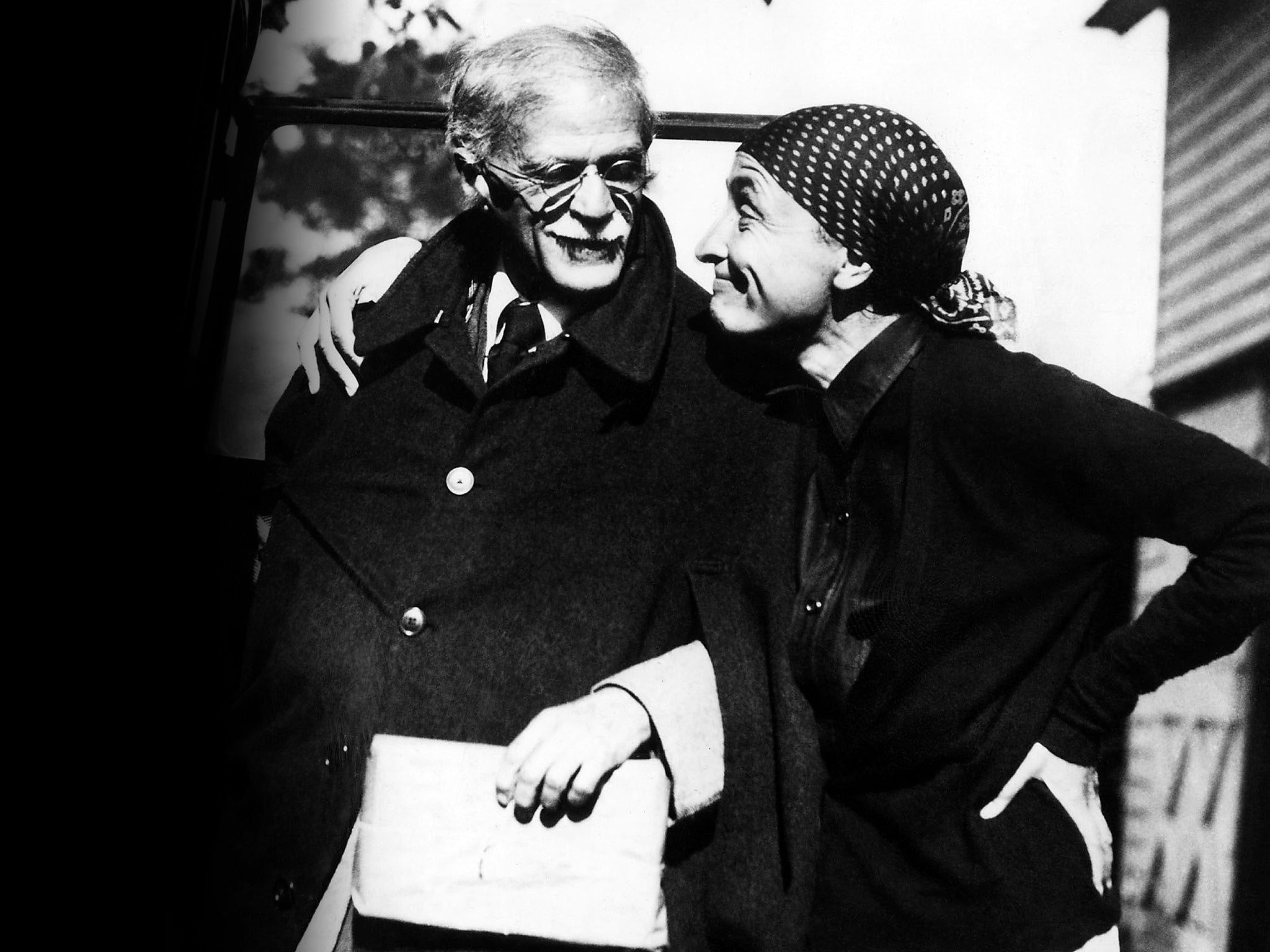

A new pop-up exhibition from the gallerist Pilar Ordovas in New York, titled Artists and Lovers, looks at the interplay between some of the greatest artist couples: Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Dorothea Tanning and Max Ernst are among the 11 artist pairings spanning the 1930s to 1970s whose work is on display in a way that highlights and reflects their influences on each other.

“This exhibition aims to bring new light and focus to a number of artists whose work has not been shown as often as it should,” says Ordovas. “Several are already being looked at today with fresh eyes: there have been a number of exhibitions in recent years dedicated to female abstract expressionists such as Elaine de Kooning. Many more of the female counterparts we have highlighted here need to be reappraised in depth, however, not just as partners but as artists in their own right.”

Stereotypically the older, more established male artist attracts a younger woman artist. Ernst was 19 years Tanning’s senior (incidentally he was still married to Peggy Guggenheim when they met); when Alfred Stieglitz and O’Keeffe met he was in his fifties and already a pioneering and successful photographer, while the Texan artist who would become known the world over for her nature-inspired paintings was in her twenties; Celia Paul was an 18-year-old student at Slade when her teacher, a fifty-something Lucian Freud, became her lover and, later, the father of her son.

“I really didn't know anything about [Freud’s] womanising,” Paul told me in an interview in 2012. “I didn't realise how predatory he was.” She later discovered that he’d taken the job as visiting tutor at the famous London art school because his relationship at the time was going wrong and “he wanted to find a new girlfriend”.

The teenage Paul, who would go on to become a celebrated painter in her own right, was caught in Freud’s spell. “The day we met he took me back to his studio, and showed me the early stages of Two Plants, which is now in Tate. I think he would have liked to have seduced me there and then, but that didn’t happen.”

Vicken Parsons: lris 24 November 2016 – 7 January 2017; alancristea.com

Artists and Lovers, 9 East 77th Street, New York, until 7 January 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks