Great Works: A Complete New System of Midwifery (1751), George Stubbs

"Yes – the history of man for the nine months preceding his birth would, probably, be far more interesting, and contain events of greater moment, than all the three-score and 10 years that follow it." That was how Samuel Taylor Coleridge marked a passage in his copy of Sir Thomas Browne's Religio Medici.

What that 17th-century doctor and antiquarian had said was: "And surely we are all out of the computation of our age, and every man is some months elder than he bethinks him; for we live, move, have a being, and are subject to the actions of the elements, and the malice of diseases, in that other World, the truest Microcosm, the Womb of our Mother."

Last weekend, it was Mothering Sunday. This weekend, it's the Feast of the Annunciation. It is the season for celebrating the womb of our mother. Admittedly the womb as such, our other world, where our nine-month pre-life takes place, has received scant attention in the arts. Even the foetus, the hero of this history, tends to be forgotten.

True, sometimes it's cast as a neonate-in-waiting, looking ahead hopefully, fearfully, to being born into real life. Or sometimes the story is about the prenatal soul, inhabiting some prenatal heaven. But who tells the epic of the foetus itself, of its life in the womb, which Browne and Coleridge adumbrate? Well, there are some pictures.

Think of Dr John Burton of York, who ended up in literature himself. He was satirised as "Dr Slop" in Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy. But his work in obstetrics has also earned him a place in English art. His An Essay towards a Complete New System of Midwifery was illustrated by George Stubbs. This was one of Stubbs's first works, and his earliest practice of dissection – using the body of a woman who died in childbed.

The images haven't been much admired. Compared with his later Anatomy of the Horse, they are a crude bit of engraving, and Stubbs refused to put his name to them. For some, it is at best a functional work. Even so, as with others of his more prosaic jobs, Stubbs finds a poetic dimension.

The human foetus in the womb is in a most dependent and imprisoned state – but it is also at its most free and independent. Its obvious limitations liberate it. It has no obligations, no competition. It is protected from enemy and hazard. It is released from gravity and resistance. It is a solitary creature in self-command.

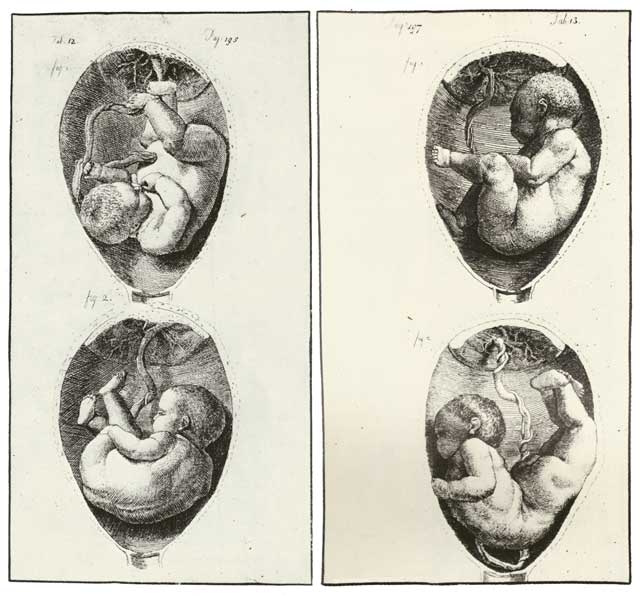

Stubbs emphasises his figures' heroism. They're not really embryos, more tough and muscular babies. Literally, what these plates demonstrate are the various ways a foetus can get mispositioned in the womb. But imaginatively, these foetuses appear as protagonists. Look across the plates – numbers 12 and 13, here – and you can read a series of extravagant actions.

These figures are like Michelangelo's ignudi, those mighty nudes on the Sistine ceiling, who strike strenuous poses. These foetuses are in self-sufficient activity. They're not doing anything. They're expressing themselves, exercising their bodies, feeling their powers, straining, tumbling, writhing. This is what foetuses would do, if they had physical self-consciousness. They would explore their strengths.

Or rather, that's one aspect of the womb-life. But unlike the ignudi, these creatures are of course not totally isolated figures. There is a relationship between the foetus and the housing womb. The isolated body exists in an isolated egg-shaped or balloon-shaped vessel.

Now it's true that there is no sense of an enclosing and supporting mother. This womb is simply a separated thing (though in other plates we're more aware of a neck at the base, as an exit.) Meanwhile, the foetus is both contained by and attached to the womb. The twisting umbilical cord connects it to the placenta. It is a symbiotic link, a union even, making them a single twofold organism. In short, what Stubbs depicts is a laid egg with a growing foetus in it – an oviparous human.

The life in the womb becomes less heroic, more ambiguous. Stubbs shows the foetus as partly active, and partly passive. We can see it as a sleeper, stirring in its slumber. The self is at one with its own world, and lives within its own dream, and exists inside its own thought bubble. It's probably the most spiritual vision that Stubbs ever made.

About the artist

George Stubbs (1724-1806) is the best English painter. Not Gainsborough, not Reynolds, not Constable, not Turner: Stubbs the horse-painter wins by several lengths. He began as a provincial in the north. He travelled to Italy. He spent two years on a full-scale visual analysis of the horse's anatomy. He went on to raise the semi-naive, vernacular practice of animal painting to extraordinary heights. He makes horses a universal metaphor: they are highly bred, trained and socialised; or romantically wild, fighting with lions; or members of a serene utopian society. He treats all his fellow creatures equally. He is a master of design – of shape, rhythm, interval. He is a great colourist, a great comedian. He hasn't yet received his due.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks