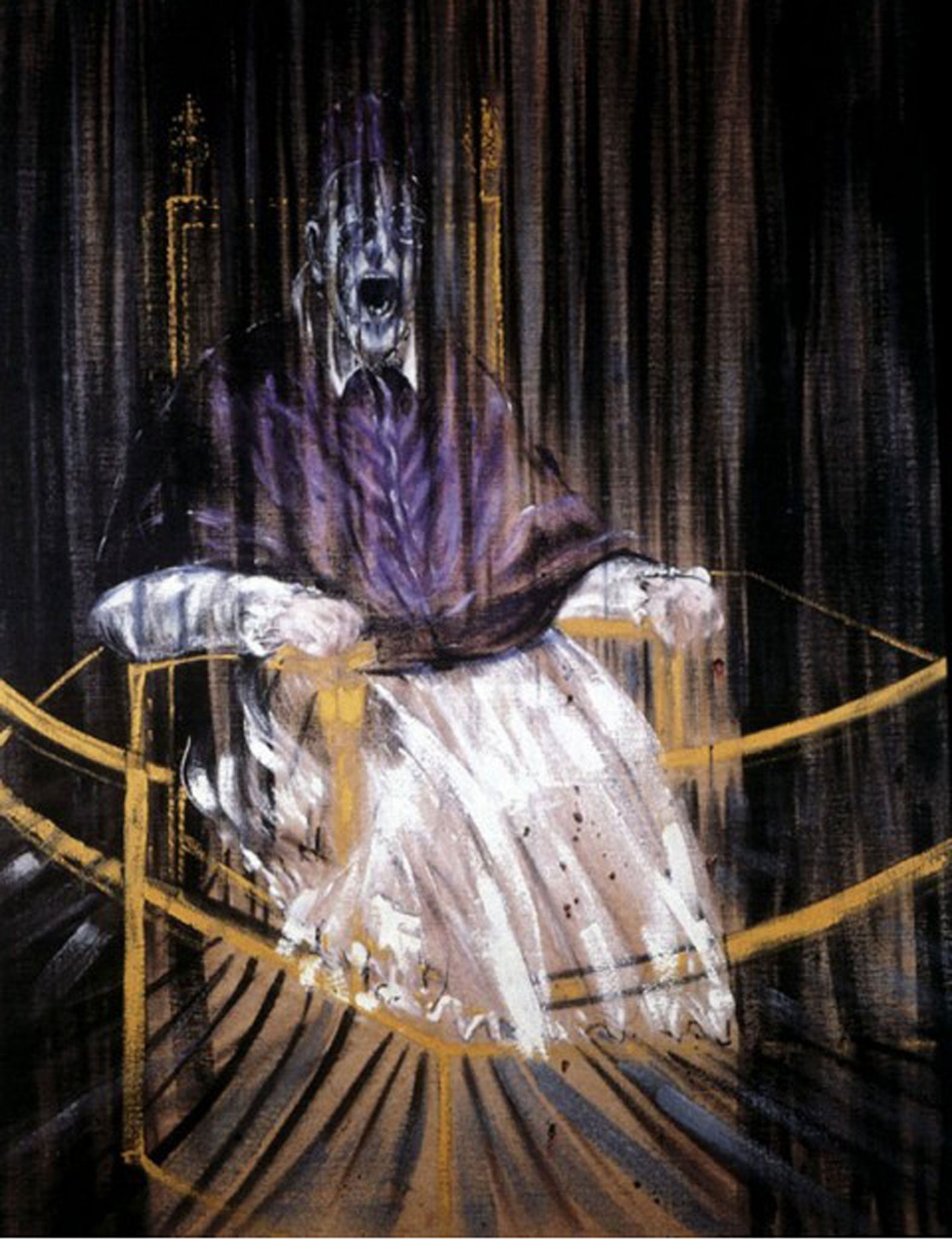

Great works: Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1953, 153cm x 118.1cm by Francis Bacon

Des Moines Art Center, Iowa

By the early 1950s, Bacon, a sometime painter and decorator from Dublin who lacked any formal education in art, had made a dramatic shift of gear. No longer entirely in thrall to the feral vision of the Picasso of the early 1930s, a vision which had led him to paint various fantastical, creeping creatures with over-extended necks that might have been of some interest to William Blake, he began to consider the possibilities of portraiture of a particularly unorthodox kind.

Portraiture? Well, you could convincingly argue that Bacon did not in fact paint people. He painted images of people mediated through a great and often blurry mashing of other images. That word mashing is quite deliberate – these images were often trodden down on the floor of his own studio, by his own boots. (Yes, it was a hellish war zone of an environment, that place.) These images were snatched from anywhere and everywhere. A new book reminds us of how indebted he was to the iconography of National Socialism.

The painting illustrated on this page is based on an image of Velázquez's great portrait of Pope Innocent X, a subject that Bacon treated – or mistreated - again and again. But the scream was never in Velázquez. Velázquez did not deal in screaming popes. It would have been more than his job of most favoured court painter to Philip IV of Spain was worth. No, the scream is snatched from a famous moment in a film by Eisenstein. Many of Bacon's images are palimpsests. Embedded within any particular image, there is often another image out of which the later image has grown. To what extent then has Bacon rendered this near sacred image utterly unholy, in fact near blasphemous?

Bacon was an atheist lifelong. We could call such a vision negative, a denial, but that would be to shrink, needlessly, Bacon's achievements as an artist. The fact is that he found his atheism exhilarating. It helped to turn his life into a terrible, continuous hazarding. This, the here and now, was all that there was, and he lived it to the limit. His painting and his life as a sado-masochist, suffering the brutalities of his lovers, were all of a piece. Life was an experiment to be lived to its utmost extremities, of pain and rapture – or perhaps it was rapture mediated through pain.

In this painting we are witness to an avowed atheist squaring up to an heir to St Peter, founder of the Christian Church. The Pope has been utterly robbed of his imperious serenity. He now inhabits a terrible, streaked, shimmery void of unknowing. His papal throne, though still gilded, and boasting certain characteristic decorative features, is transmogrifying – it seems to be happening before our very eyes – into something else, a corral or cage-like shape. The strokes of paint, vertical and then fanning out, could be desperate clawings. The Pope is in the throes of becoming trapped inside that which once served to emphasise his hieratic eminence. The chair on which he sits, fiercely gripping its arms, almost seems to be in motion. It spreads, it weaves about, it encircles, it whip-lashes. It also lacks groundedness, solidity.

For all that, he grips it in order to re-find some stability. Even as we stare, we seem to be falling backwards into the painting's deep space. It is that scream which holds our eye. It is part a feral shriek, the wide-mouthed involuntary cry of the pure animal. It is also perhaps a breaking out, a denial of his role as leader of the church, which is given such definition by his gorgeous vestments. This scream is not Munch's over-familiar scream. Munch represented his scream as a form of infection, a spreading stain. It rippled outwards and outwards, giving shape, definition, form, to the entire dream landscape of which it was its centre. This scream is the Pope's darkness. It is all that he is. It is what he amounts to in the end, a small, black knot of humanness.

And yet this scream is not quite a denial. The entire enterprise of this painting seems to suggest otherwise. Its scale and pretensions are magnificent, monumental. To scream against the denial of the light is also a self-vaunting, heroic thing. It is all that man was ever born to.

About the artist: Francis Bacon (1909-1992)

Francis Bacon was born in Dublin of English parents. His early life was one of a drifter. His prodigious talents were not widely recognised until the beginning of his fifth decade. Aside from his achievements as a painter, he was known for the life of libidinous and alcoholic excess that he chose to live. In short, his sado-masochism fed his vision. His life as a no-holds-barred roisterer at Soho's Colony Club in the 1960s helped to give definition to that hedonistic decade.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments