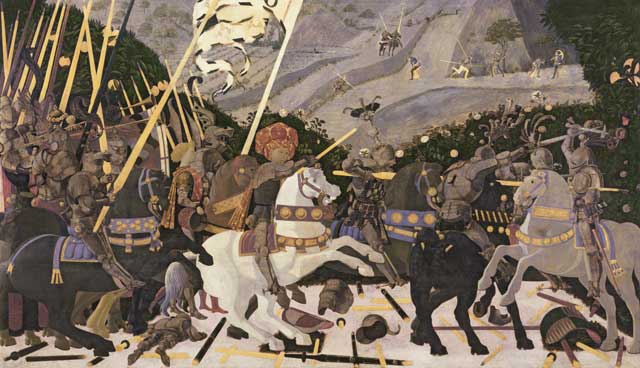

Great Works: The Battle of San Romano 1438-40 (182 x 320cm), Paolo Uccello

National Gallery, London

The pity of war? The squalor of war? The no-holds-barred misery of war? Not necessarily. It rather depends upon three quite separate factors: the subject matter of the painting, who may have commissioned it, and the point of view of the artist. What we know for sure is that art often tells lies about history because history belongs to the victors, and they do so love to be reminded of their victories, which, in the mind's eye, stretch and stretch away into the future.

Take this great painting by Paolo Uccello, for example. It is one of two by this master which hang in Room 54 of London's National Gallery. This painting of the Battle of San Romano, which brazenly dominates an entire wall, is not really a painting of a battle at all because that battle, according to some, was little more than a skirmish between two perpetually warring Italian city states, Florence and Siena. That skirmish happened on 1 June 1432, just north of Florence, close to the town of Montopoli in Val d'Arno. It was painted in about 1540, just eight years after the skirmish itself took place. Uccello did three separate versions, and the glossiest of them is in the Uffizi in Florence because Lorenzo de Medici was so enamoured of the scene that he snatched it from its original owners and hung it in his Florentine palace in the belief that the image would do the reputation of the Medicis no harm at all. The version we see here is also magnificent, but it lacks some of the gilding that it would once have had. More's the pity.

It is a wonderful painting, and all the more beguiling because it tells such brazen lies about the nature of warfare. It is so decorous in its portrayal of the balance of forces, for example, so exquisitely fussy in its detailing. See how the gorgeous, plumped-out, pumpkin-like, quangle-wangleish hat of the leader of the Florentines, Niccolò da Tolentino, utterly dominates the centre of the scene – that hat and Niccolò's gorgeous, rearing, bulbous-eyed white horse, which has all the look and the almost festive unreality of a carnival charger into whose rump we might wish to slip a coin in order to make it buck and heave pleasingly, are enormously visually arresting. This hat seems to be handed to us ceremoniously, like a casket from the hands of Portia. And beneath that hat there is the serenely disinterested face of the military commander himself, who was in fact a mercenary.

Look, too, at the face of the beautiful boy who rides behind him, he with the spillage of golden curls. Why are they not wearing protective headgear, too? Well, they would be much less affecting if their faces and heads were disguised in that way, wouldn't they? The boy looks fresh-faced as an angel wrested from an icon.

How astonishing that these two should have such beautifully disengaged expressions on their faces when they are in the thick of battle! And thick is exactly the word. Squeezed, close-pressed might be others. So artful is Uccello's composition, it is as if he has squeezed all the action into the foreground: see how all that luscious vegetation, complete with those mysteriously bulbous orange fruits – they look a little like the kind of fantastical fruits that might have been painted by Henri Rousseau nearly 500 years later – seem to press the cavalry towards us, and how the rising fields behind, once again, contribute to that visual sense that everything of urgency is happening at the front of the canvas – which means in front of our very eyes.

And yet, the commander and his gorgeous male companion aside, it is not so much warfare that we are seeing here as pageantry – see how those lances are tilted in the same direction, and how little evidence of genuine gore or human suffering of any kind there is to be seen. No, much more important is the careful delineation of all that beautifully articulated armour, and the caparisoning of those horses.

There is death here, certainly – yes, there is a foreshortened corpse in full armour lying on that lovely pink carpet of ground that serves as the central killing field. And yet here, once again, there is nothing of the mess, squalor and the sheer disorganisation of battle. Everything is beautifully disposed, broken staves like a carefully plotted move in an intense game of spillikins. And the way in which that dead man is lying puts us in mind not so much of death, as of the fact that Uccello was completely besotted by the relatively new discovery of single-point perspective, ever so concerned, always, that everything should be just so, even in death.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

The Florentine painter Paolo Uccello (c. 1396-1475), having served as an apprentice to Lorenzo Ghiberti, made paintings that combine an often quite severe formal rigour with a fantastical imagination; his colour schemes in particular are rich and unpredictably various. The three versions of 'The Battle of San Romano' (the third of which is in the Louvre) are his best known works.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks