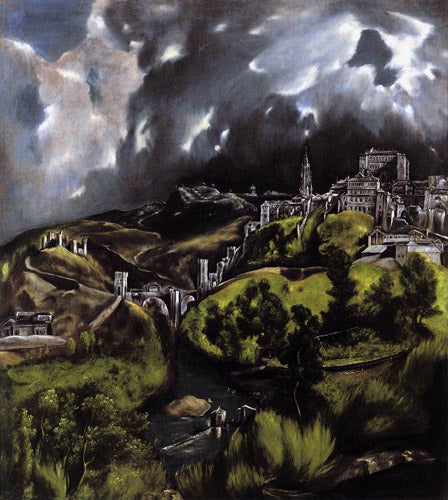

Great Works: View of Toledo (c1600), El Greco

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Imagining the end of the world became popular in the 20th century. At last we had the tools to finish the job, all by ourselves, with no divine assistance. H G Wells's The War of the Worlds (1898) might pin the coming disaster on alien invaders, but the war machines from Mars represent fears about our own capacities. The Book of Revelation could be rewritten in terms of technology. The supernatural was superseded. The catastrophe was now.

We had a new artistic language to picture it with too. It wasn't a matter of showing literal destruction. Images themselves went into convulsion, fragmentation, incandescence. In Futurism and in Expressionism, the apocalyptic became a normal idiom. It didn't even need to carry a feeling of horror or doom.

There was the Berlin Expressionist, Ludwig Meidner. On the eve of the First World War, he painted a series of pictures explicitly titled Apocalyptic Landscapes, showing the city, shattered and consumed. The streets rock. The houses judder. The sky breaks up in zigzags and shoots out in firestorms. To us, they look clearly like a premonition of the coming terrors. To the artist, it was (in part at least) a wild celebration of modernity. Meidner said: "Let us paint what is near to us, the town which is our universe, the streets full of tumult, the elegance of its iron bridges, its gasometers hanging in mountains of clouds, the shrieking colours of its autobuses and its express trains, the swaying telegraph wires..."

The modern art of derangement didn't arise only from war anticipations. It could be a reflection of the new, wonderfully disorienting world. Meidner's apocalypses are both positive and negative, an ecstasy and a nightmare, either way exciting. And this sensibility, whether it's aghast or energised, also encouraged a keener feeling for older art: El Greco, for example. El Greco's View of Toledo is another crazy vision of a city. Call it apocalyptic, and most people will agree. It's what you'd expect from an intense Spanish counter-reformation spirituality. The Book of Revelation is a subject that El Greco directly addresses elsewhere. But where is apocalypse exactly? And what kind?

What's striking about the painting, subject-wise, is that it lacks any event. It's a remarkably pure landscape or townscape. It has a few, tiny figures, but little sign of habitation or activity. And it's certainly without angels, beasts, flame, earthquake, the risen dead – the usual second-coming attractions. True, the city's geography is partly rearranged, and on the far left side a group of buildings is possibly floating on a cloud (or possibly not). But the evidence of apocalypse here is mainly metaphorical.

Extreme and enveloping natural phenomena stand for the supernatural, and the way the scene is painted makes it all the more visionary. Instead of the Opening of the Seventh Seal, the heavens open, and a storm ricochets through the whole picture. The sky is exploding. It flashes, rolls, wobbles like a thunder sheet, bursts like a shell. The ground is staggered. It architecture tumbles down the hillside as if down flights of stairs. The jumpy lines of buildings look struck by lightning, or simply like forked lightning taking built form.

Apocalypse is a matter of light, paint, form, exaggeration and disintegration, and this is what makes View of Toledo seem modern. Whether it's a positive or negative apocalypse is hard to judge. But in the Christian story, whatever happens on the way, the end of the world is ultimately a happy ending. And making Toledo into the setting for the world's final throes, El Greco is paying his adopted city a great compliment. It becomes, in dread or glory, a holy city.

Everything said so far has cast View of Toledo as a visionary scene, awesome and overwhelming. But it's possible to see it under quite another aspect, as a small and well-managed scene – a landscape made according to the sort of procedures described by one of Thomas Gainsborough's contemporaries. "I... have more than once see him make models – or rather thoughts – for landscape scenery on a little old-fashioned folding oak table... He would place cork or coal for his foregrounds; make middle grounds of sand and clay, bushes of mosses and lichens, and set up distant woods of broccoli".

El Greco's city is likewise a made-up world, a contained environment. The artist may not actually have set up a broccoli scene in his studio. But his image is visibly assembled from pieces, from turf sections, green sprigs, miniature walls and buildings. Even the sky is a cotton-wool fiction.

It is like the little magic kingdom remembered by C S Lewis: "Once in those very early days my brother brought into the nursery the lid of a biscuit tin which he had covered with moss and garnished with twigs and flowers so as to make it a toy garden or a toy forest. That was the first beauty I ever knew."

And at the same time this table- top/biscuit-tin world is shaken by spasms, as in Meidner's "gasometers hanging in mountains of clouds, the shrieking colours of its autobuses and its express trains, the swaying telegraph wires".

A scale model; an apocalypse: View of Toledo is both, which is odd, since these modes should be direct opposites. An apocalypse shows the world as an arena for transcendent and tumultuous forces. A scale model shows it as our careful plaything. An apocalypse declares divine power over us. A scale model suggests our own magical control. In this scene, two forms of world-handling are strangely fused.

About the artist

Domenikos Theotocopoulos (1541-1614) was born in Crete, where he trained as an icon painter in the Byzantine tradition. He moved to Italy, and assimilated the Renaissance accomplishments of Venice and Rome. He ended up in Spain, where he got his nickname, the Greek, and turned into one of the strangest painters in the Western tradition. His subjects are mostly religious, while his images burst in flashes, stretch and shrink as in a fairground mirror, switch angles, fragment, dissolve, and suddenly become clear.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks