Signorelli, Luca: The Resurrection of the Flesh (c.1500)

The Independent's Great Art series

It is one of St Paul's most spine-tingling passages. "Behold, I tell you a mystery: we shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed – in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised incorruptible, and we shall be changed. For this corruptible must put on incorruption, and this mortal must put on immortality."

And every Sunday, when Christians say their creeds – "I believe in the resurrection of the body", "I look for the resurrection of the dead" – they affirm this queer point of faith. When we die, we shall not say goodbye to our bodies forever. At the end of the world all of us, those dead and those still alive, will be clothed in an immortal body, which will be our own individual body, but renewed.

As theologians have explained, even in the afterlife there are no human souls without bodies: an immortal soul requires an immortal version of the flesh it had once had. But since this new body must have no imperfections, it cannot be that of, say, a child or an old person. It must be a body in the full vigour of life. Some authorities specified that everyone would resurrect at the age of 33.

The doctrine honours the human body, by insisting that we cannot, in any circumstances, exist without one. But when it comes to imagining this incorruptible flesh, theology describes something from which almost all the physicality is removed, which doesn't seem much like a body at all.

Resurrected bodies have four essential characteristics, technically defined as clarity, impassibility, agility and subtlety. They shine brightly. They cannot suffer or die. They can move as freely and as quickly as they like. They can pass through other objects. Altogether it sounds like a subject for the strange world of painting.

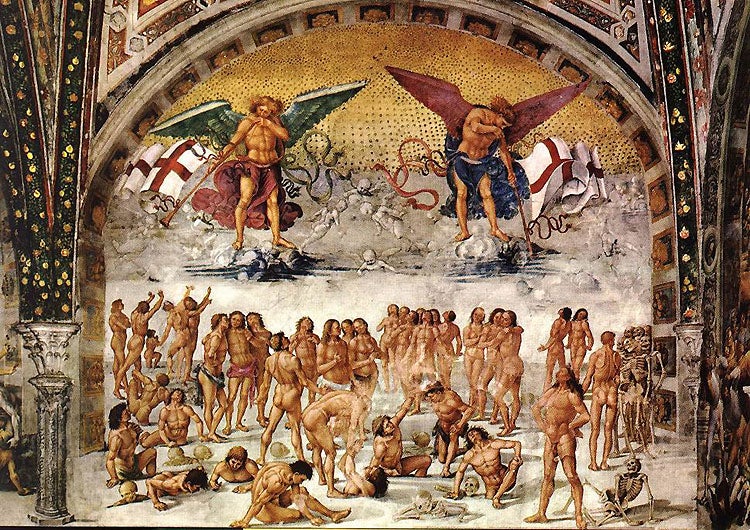

In the Capella Nova in the cathedral of Orvieto, Luca Signorelli made frescoes illustrating the end of the world. You can see the prophesied sights of the last days unfolding before your eyes – the great destruction, the reign of the Antichrist, the rounding up of the damned, the crowning of the blessed. Every scene is thronged with figures. Half way through, there's The Resurrection of the Flesh.

Two giant angels with long trumpets stand in the sky, blasting. Below them the earth is an off-white, flat and featureless stage, stretching away and stopping at an abrupt horizon in the middle distance. Its plain whiteness sets off the bronzed flesh and the shadows of the risen and rising humans, both male and female. They are joined by a smaller number of skeletons.

So some have emerged already in their new flesh, and the skeletons are waiting to put it on. A gang of boneys on the right are laughing at a body now in mid-metamorphosis, just acquiring its cladding of muscle. Mainly the figures stand around, exercising and enjoying their superbly strong new anatomies. They pull themselves up through the ground, and offer helping hands, and gather and embrace in a big reunion.

It's a very Renaissance scene: a display of magnificent physical specimens, not so different from one another, shown in a variety of poses and angles. It's like a cross between a gym and a passeggiata, and a modern viewer can't help getting a subliminal, anachronistic impression of the seaside.

But Signorelli doesn't show much interest in the supernatural side of his resurrected bodies. The enfleshing process is only briefly indicated. Their "agility" and "subtlety" are not apparent at all. (The blurriness in the middle of the picture is decay.)

The physical miracle is located elsewhere – not in the bodies, but in the ground. Traditionally, in resurrections, the dead rise from opened-up earth graves, or from stone tombs whose lids have flipped off. Here, Signorelli imagines them directly rising through the surface of the earth, like worms.

The flat ground is another Renaissance feature. It's like the perfectly level stone floor of a piazza depicted in a perspective scene. But here it's cleared of buildings, and made of an unimaginably ambiguous substance.

It's a kind of membrane, or quicksand, soft enough for a body to pass through, and it hugs the penetrating limbs closely, and closes behind them. But at every other point it's firm enough to stand on, and offer leverage. Painting's ability to depict the impossible comes fully into play.

The Artist

Luca Signorelli (1441-1523) was a Renaissance virtuoso of the human body. He was taught by Piero della Francesca and later earned the admiration (and perhaps imitation) of Michelangelo. He did a lot of church painting, and some frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. His other great works are frescoes in Tuscany – the scenes from the life of St Benedict in the Abbey of Monte Oliveto at Chiusure; and the Last Judgement scenes in the black-and-white striped Cathedral at Orvieto. Out-geniused by Raphael and Michelangelo, he returned to his birthplace, Cortona, and became a rather boring provincial master. But in his vision of the Apocalypse, with flying devils attacking men with jets of fire, Signorelli seems to have fully anticipated the dive-bombing and rocket warfare of centuries to come.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks