Back to square one with Kasimir Malevich's new exhibition at the Tate

Claudia Pritchard previews a new show at the Tate devoted to Kasimir Malevich, the Russian painter who shaped an art revolution.

Nothing can have prepared visitors to an exhibition in December 1915, inside an apartment block on Marsovo Pole in the newly renamed Petrograd, for what they were to see. At the oddly named 0,10 Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings they were confronted by walls of canvases showing no recognisable images – no portraits, still lifes or landscapes – but rather apparently random arrangements of geometric shapes.

And presiding over the erratically hung paintings, in the high corner traditionally reserved in the Russian home for a religious icon, was not a Madonna and Child or Christ in Majesty, but a stark, black square.

This uncompromising statement was the work of 36-year-old Kasimir Malevich. Crudely over-painted – X-rays reveal an earlier, chromatic work beneath – it was, like so many landmark works of art before and since, cited by at least one critic as proof of the death of painting. But its legacy was far-reaching, liberating the artist from the figurative, as even recent, rising or contemporary movements in the West, such as Cubism and Surrealism, did not do, with their bottles and guitars, mannequins and found objects.

At Tate Modern, visitors to Malevich: Revolutionary of Russian Art, opening this month, will be able to experience something of the amazement of walking into 0,10, which is being replicated as faithfully as possible, with the help of a single, precious archive picture of the original event. Then, 39 new works were shown, of which 20 can be seen in the photograph; other artists, including Popova and Tatlin, were also exhibiting, but their involvement in one of the most groundbreaking exhibitions of the 20th century is often overlooked. Malevich had for months been painting virtually in secret, unleashing in one go dozens of small canvases on which danced blocks of pure colour.

The black square – there are several versions – was to become Malevich’s personal motif. At his funeral in 1935, the hearse had one strapped to the radiator, and his gravestone also bore one on a slab of white. It was as far as visually possible from the rococo excesses of the Romanovs, whose 300-year rule was coming to its end at the time of the Last Futurist exhibition. In place of the czars’ supremacy, Malevich created his own “suprematism”, his own word for art where colour and form alone communicate, untrammelled by props.

“The art of painting, sculpture, the word, was up until now loaded with all kinds of rubbish – odalisques, Egyptian and Persian kings, Solomons, Salomes, princes, princesses, and their favourite little dogs,” he wrote in a pamphlet accompanying the exhibition. “Painting was a necktie on the starched shirt of a gentleman and a pink corset holding in the stomach of a fat lady.”

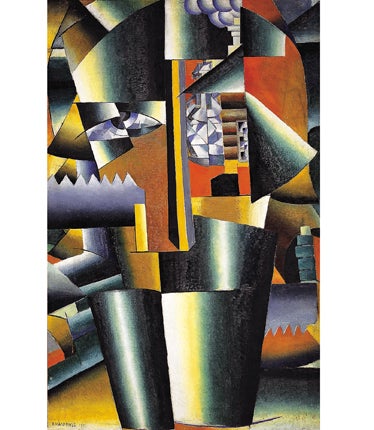

But the discomforting black square had, in 1915, already had a life elsewhere. In 1913, the year that Stravinsky and Diaghilev turned the dance world upside down with the rawness of The Rite of Spring, Malevich had worked as designer on an opera, with a group of friends including the now little-known composer Mikhail Matyushin. Victory Over the Sun, performed at Luna Park in St Petersburg, was a crazed futuristic fantasy, sung in an invented language, Zaum, peopled with characters and creatures from other planets, and telling in jagged fragments the eye-popping fable, with its undisguised allusions to the fall of the tsars and challenges to religious authority, of the Sun’s redundancy and obliteration. The outlandish costumes designed by Malevich were richly coloured and made the actors look like three-dimensional versions of the conically constructed subjects in his 1912 pictures, The Woodcutter and The Scyther.

There was an appetite for the avant-garde in 1913 that would be dulled by the First World War, but in December of that year two performances of Victory Over the Sun sold out, and the audience divided, rewardingly if predictably, into those who hailed a new masterpiece and those who cried: “Enough!”. There was a revival at the Barbican in 1999 which prompted similarly mixed reviews, but it is rarely staged, so footage at Tate Modern showing an extract from an American production will be new to most. I saw this in the show’s previous incarnation last year at the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, from whose vast Malevich collection many pieces are being loaned to the Tate, and can vouchsafe for the opera’s compelling madcappery. And the set design is dominated by a square, divided diagonally into black and white sectors – the antithesis of the round, yellow sun and the prototype of Black Square.

Between Victory Over the Sun and 0,10 Malevich, now avant-gardist-in-chief, defied other conventions about the job of art with a succession of works in which recognisable objects featured but were depicted without a relationship of narrative or scale. In An Englishman in Moscow (1914) a top-hatted gent stares flatly out from behind a fish; a scimitar, a lit candle, a tiny church, scissors and a large red wooden spoon, (as worn, brooch-like, by anarchic artists at the time) float across him, with printed words and parts of words: “time”, “darkness” “partial”. The references to Cubism are clear, but here too is the juxtaposition of unconnected objects found in the contemporary work of de Chirico, and the suspended animation of Chagall.

With the 1917 revolution, the avant-garde became the establishment. Malevich was given important teaching and administrative roles. Suprematism was absorbed into daily life: the façade of the White Barracks in Vitebsk, for example, that now housed the offices of the city’s Committee for the Struggle against Unemployment, was decorated with his triangles, circles and squares. By 1923, Malevich was appointed temporary director of the State Institute of Artistic Culture; under Stalin, in 1926, he was dismissed for alleged counter-revolutionary activities.

Late in his career he would return to figurative painting, but suprematism had left its mark: on his way towards late naturalism, in the late 1920s and early 1930s, it is as if he rediscovers the other-worldly figures of Victory Over the Sun. With his budetlyane – “men of the future” – the peasant subjects of his early work are revisited and rendered monumental. Head of a Peasant (c 1929-32) has the symbolism and dignity of an icon – the very sort of image that he had sought to challenge with the once daring, now much-admired, Black Square.

‘Malevich: Revolutionary of Russian Art’ runs at Tate Modern (tate.org.uk) from 16 July to 26 October

Self Portrait (1910)

A Life in brief: Kasimir Malevich

by Jamie Crow

23 February 1879

Born to Ludwika and Seweryn Malewicz, ethnic Poles who had settled in Ukraine following the Polish uprising of 1863.

1904-1910

Studied at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture and in the studio of Fedor Rerberg in Moscow, and began to participate in various exhibitions with the Soyuz Molodyozhi (Union of Youth) in St Petersburg.

1912-1913

Became more experimental, adopting a Cubo-Futurist painting style and designing the stage set for avant-garde opera Victory over the Sun, which included a black square placed against the backdrop of a sun.

1915

Published his manifesto From Cubism to Suprematism, which announced his move on from cubism and laid down the foundations for the concept of the radical abstraction of Suprematism.

1915

The first “black square” was exhibited at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, and was considered by many to be the breakthrough for Malevich’s artistic career.

1923-1926

Appointed temporary director of the State Institute of Artistic Culture, only to be dismissed three years later by Stalin for alleged counter-revolutionary activities.

1927

Travelled from Warsaw to Berlin and Munich hosting foreign exhibitions that finally gave him international recognition.

15 May 1935

Died from cancer. On his deathbed, a black square was hung above him in memorium.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks