Decaying importance: Britain's ruins tell important tales of our times

Tate Britain's new exhibition on ruins tell us something about ourselves

Ruins are the architectural equivalent of a celebrity breakdown. Which is to say we can’t stop looking at both: just as broken people are the perfect fuel for fiction, so broken buildings are the perfect fuel for art. And not only do they show us what the past was like, but they’re also “places where a future might be imagined or invented”, believes Brian Dillon, the curator of Tate Britain’s new exhibition on the subject, Ruin Lust.

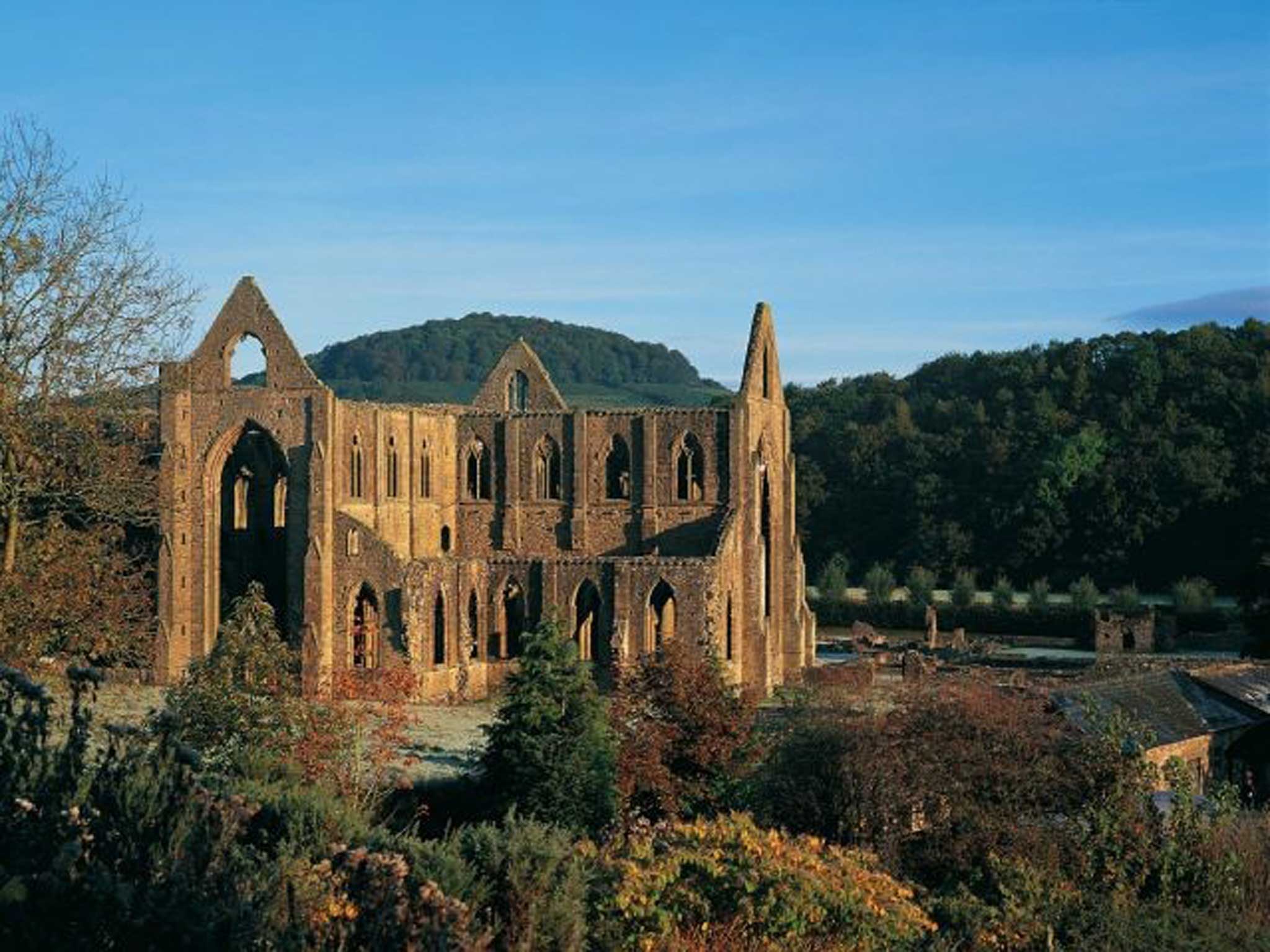

This exhibition makes you think. Ignore the mixed reviews – it’s actually the most provocative thing Tate Britain has put on for some time. We need to celebrate ruins – or at least commiserate with them. The show features work across the eras from Turner’s painting of Tintern Abbey to Laura Oldfield Ford’s 2010 photo of the abandoned, now-demolished Ferrier Estate in south-east London, one of the most striking images in the show.

Oldfield Ford believes that ruined urban landscapes are essential – a “reliquary, a place where memories and voices can be tuned into, channelled, and in some way transmitted” – and her work encourages us to consider the ruins of the future: crummy new flats that could end up as the dilapidated inspiration for artists looking back at the way we lived in the 2010s, artists who might mock our slavish devotion to the bottom line, to property ownership.

Cheap and nasty pre-Bust apartment blocks are already flaking; the new towers behind central London’s King’s Cross are duds. There’s a huge hole in the centre of Bradford where a shopping mall deal fell through; degenerate Neoclassical mansions on London’s famously wealthy Bishop’s Avenue stand derelict. Cash mangles the landscape.

While ruins may not be chocolate-box pretty, aesthetically, politically or otherwise, they tell important tales of our times. Another devotee is the essayist and film-maker Patrick Keiller; his last film, Robinson in Ruins, eyed ruins within the British landscape, picking out abandoned cruise-missile shelters and peeling road signs as being of high cultural significance, modern-day Stonehenges.

Ruins are failures. Something’s gone wrong. But we’re too ready to paper over the mistakes. England’s greatest ruin is the fire-ravaged stately home of Witley Court in Worcestershire. It is being slowly patched up – but its spookiness is its attraction. I think we should leave Witley be. If you want to see aristocratic bad taste in all its swaggering glory, go around Sandringham.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments