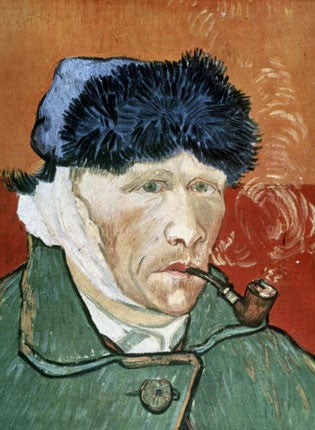

Was truth the biggest casualty in the case of Vincent and his severed ear?

It wasn't self-mutilation – and Gauguin was to blame, say German art historians

The history of art, and the history of ears, may never be the same again. According to a new book, the painter Vincent van Gogh did not slice off his left ear in a fit of madness and drunkenness in Arles in December 1888. His ear was severed by a sword wielded by his friend, the painter, Paul Gauguin, in a drunken row over a woman called Rachel and the true nature of art.

Gauguin lied about the incident and fled, two German art historians now believe. Van Gogh covered up to protect his friend and was placed in a mental institution. He committed suicide seven months later.

If confirmed, the new theory – based on a re-reading of police reports and witness statements – could explode the standard image of Van Gogh as an unstable man, teetering on the frontier of madness and genius. In the revised version of events in Arles on Christmas Eve 1888, Vincent emerges as a mentally fragile, quarrelsome drunk but also as a loyal friend, who took Gauguin's secret to his grave.

Other Van Gogh scholars are intrigued but not convinced. Researchers at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam prefer to stick to the familiar story: Vincent severed the lower part of his own ear, wrapped it in newspaper and asked a prostitute called Rachel to "keep this object carefully".

The accusation that it was Paul Gauguin who committed grievous bodily harm on his friend is published by Hans Kaufmann and Rita Wildegans of Hamburg University in a 392-page book, Van Goghs Ohr, Paul Gauguin und der Pakt des Schweigens (Van Gogh's Ear, Paul Gauguin and the Pact of Silence.)

The authors have re-examined contemporary police reports and surviving, second-hand accounts of witness statements, including contradictory declarations by Gauguin. They admit that final proof is lacking, and that the police investigation into a drunken brawl between two artists was half-hearted at best. Nonetheless, they say that all the evidence points to the fact that Gauguin accidentally sliced off his friend's ear.

The two men were arguing in the street, the authors believe, partly about their competing interest in Rachel but also about the correct way to paint. Van Gogh argued for painting from the life; Gauguin from the imagination. The French painter was threatening to leave for good, wrecking Van Gogh's dream of founding a utopian artists' colony in Arles. Gauguin, a keen amateur fencer, walked into the street with his luggage and his sword, the authors believe. Van Gogh pursued him. Gauguin brandished the sword in his friend's face to keep him at bay and accidentally cut off part of his ear. Van Gogh then staggered to Rachel's house and handed her the severed part.

The next day both men gave statements to the police. Gauguin accused Van Gogh of self-harm and said that he had seen him stumbling through the streets with a razor in his hand. Van Gogh mumbled incoherently, accusing neither Gauguin nor himself.

After examining the evidence, Kaufman and Wildegans say that Gauguin contradicted himself several times and claimed to have seen events he could not have seen. Other witnesses suggest that Van Gogh provoked Gauguin and Gauguin attacked Van Gogh.

The two men never met again. Gauguin returned to Paris and then emigrated to the French Pacific island of Tahiti. Van Gogh was placed in a mental institution and then moved to the village of Auvers-sur-Oise, near Paris. After an extraordinary final burst of creativity, in which he painted 70 paintings in 70 days, he shot himself on 27 July 1889 and and died two days later, aged 37.

Why should Van Gogh have covered up for Gauguin? "He hoped that by doing so, he could force Gauguin to resume their life together. He obviously adored him," Kaufmann said.

If the incident had not happened, the German authors argue, Van Gogh might not have been placed in a mental institution. He might not have plunged into a depression, aggravated by poisoning from the lead and arsenic in his paints. He might have gone on to live to a ripe old age, like Claude Monet, and he might have painted many, many more canvases. Nina Zimmer, curator of a large Van Gogh exhibition at the Kunstmuseum in Basle until September, is unconvinced. "Maybe they are right," she said. "But almost any theory is plausible because there are so few established facts."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments