Caravaggio's Friends & Foes, Whitfield Fine Art, London

In the 400th anniversary year of Caravaggio's death, we have been presented with several ways to know the painter, or to know the man. Those lucky enough to visit Rome recently may have seen a huge exhibition of major works by the artist. Star archaeologists have claimed, within the last few months, to have found the artist's bones, and more, have speculated that they contain lead, attributing his death to his lead-based paints. The British art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon has just published his biography of the artist– a labour of 10 years' work – refuting this thesis.

Caravaggio's life was extremely dramatic: feuds, madness, chases, and of course, his murder of a man in a street brawl. More importantly, though, his paintings, to this day, have a drama that outstrips all of those stories. His paintings have a hold on the viewer that is absolutely immediate. Caravaggio's naturalism, alongside the drama of chiaroscuro (dramatic light and shade), gives the visceral sensation that you are witnessing an instantaneous moment of revelation.

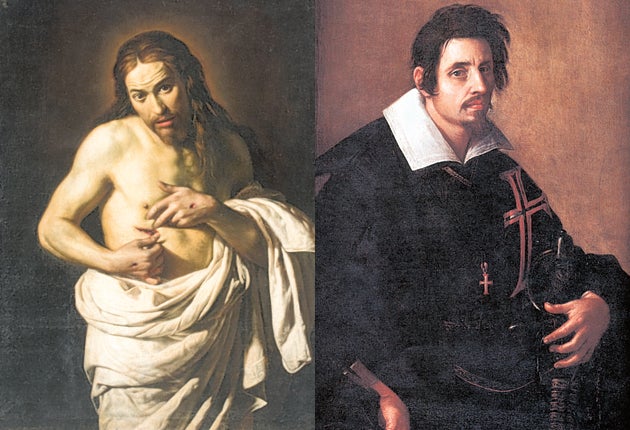

At Whitfield Fine Art is an exhibition that attempts another way to understand the impact of Caravaggio – in an exhibition of paintings by his "friends and foes". That is to say, his detractors and rivals from the period, and those who were friends of the artist, or followed in his footsteps. As such there is some narrative drama surrounding some of these paintings. There is a self portrait by Giovanni Baglione – the rival artist who famously sued Caravaggio for libel. The painting looks rather pompous and arrogant – "anything you can do". There are beautifully rendered bunches of grapes and dramatically lit putto. Lo Spadarino's Christ Displaying His Wounds has a corporeal shiver to it as Christ, draped in white folds of cloth, fingers the bloody wound in his side. There are also some paintings here, however, which appear to be simply a collection of unremarkable old master works that have one little thing or other in common with Caravaggio: lighting, bodily horror, grapes or models with everyday features.

There are a few great moments in this exhibition. It's interesting to see several renderings of the same scene and models by different painters, a group of Flemish, French and Dutch artists who worked together in Rome in the Bentvueghels group – the "birds of a feather", some of whom were followers of Caravaggio. Jean Ducamps' painting, The Liberation of St Peter, for example, is beautifully composed, and gives a gentle, dozing sense of the sleepy figures it contains. The glow of an angel throws light across the scene, most distinctively against the armoured arm of a sleeping guard (Caravaggio's The Taking of Christ, 1602, has armour similarly rendered). The scene is repeated with similar models by Antonio de Bellis, with St Peter in a blue robe, contrasting with the papery white gown of the angel that almost crunches.

Such moments aside, there's a big problem here, which is almost too obvious to point out. With traces of the Caravaggesque everywhere, the keen sense of what you are missing from the master himself is all too apparent, so it's hard not to leave feeling somewhat eluded and, ultimately, bereft.

To 23 July (020 7355 0040)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments