Charles Darwent on Lowry and The Painting of Modern Life at Tate Britain: The matchstick men aren’t quite where Lowry left them

L S Lowry turned the working class into a flat-capped mob, always on the move, never getting anywhere

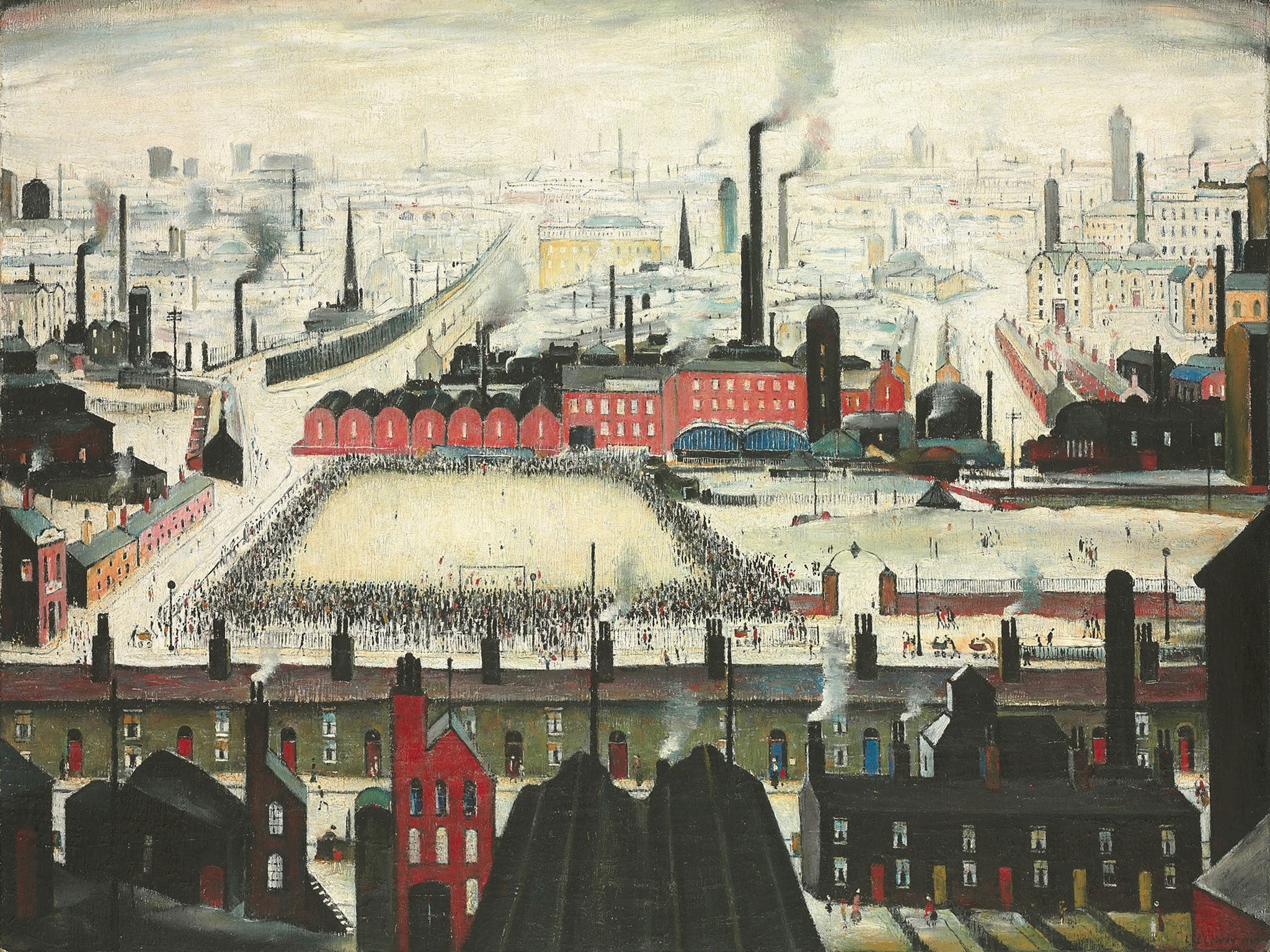

Fancy a Lowry? It’ll cost you. In 2011, The Football Match, in Tate Britain’s new Lowry show, sold for £5.6m. This wasn’t a one-off. Last year the (misleadingly) cheery-sounding Fun Fair at Daisy Nook was knocked down at £3.4m, while Industrial Landscape went for £2.6m. Scenes of inhuman poverty – hungry mill workers, fever hospitals, smog, cripples, beggars, street-fighting drunks – come at a price.

Who buys them? The answer – duh – is rich people. Uniquely for a Tate blockbuster, two-thirds of the works in this show have been lent by private owners. Everyone loves a Lowry, except for institutions: the Tate’s is the first exhibition of his work in a major gallery since his death in 1976. Nor does Mr Stick-Man appeal only to hedge-fund managers. You do not have to be psychic to see queues in Tate Britain’s stars.

And so, another question: why does everybody love Lowry? Certainly not because they think of him as this show would like us to.

Modernism is in vogue again: thus all the recent exhibitions trying to persuade us that Chagall/George Bellows/whoever was a modern painter, really. The subtitle to this one, The Painting of Modern Life, comes from Baudelaire via T J Clark, the historian who demonstrated, in 1985, that Impressionism had been as gritty as it was pretty. Clark is co-curator of this exhibition, and makes his point again. Lowry, taught in Manchester by a Frenchman called Adolphe Valette, did sign up to Baudelaire’s views on modernity. But he did so in the mid-1920s, 60 years after the French poet voiced them.

Lowry was never a modern painter, in other words, but a wilfully old-fashioned one. That was true in 1925, and even truer in 1971 when he painted Mill Scene, in this show’s first room. In terms of stylistic progression, it is hardly different from Outside the Mill of 1928. Nor in terms of subject, although by 1971 Manchester’s cotton industry was 40 years dead.

“I’ve a one-track mind,” Lowry said. “I only deal with poverty.” That was an understatement.

Oddly, if you ran through the Tate’s six large, Lowry-filled rooms, the resultant blur might almost look modern. His unvarying compositional recipe calls for a terrace of houses parallel to the picture plane, on a street parallel to the bottom of the canvas, with another street running off it halfway along at right-angles. Add to this Lowry’s habit of outlining things in black and you might almost think you’d seen a modernist grid. You won’t have done. Nor – although, at speed, they might look like them – do Lowry’s rickety people have anything to do with the biomorphic squiggles of Kandinsky or Miró.

I wonder, though, if they don’t look like germs even so? Walking around this show, I was reminded of Henry Moore’s Shelter drawings. It has always seemed to me that Moore, a Northerner like Lowry, hated the proles he found sheltering from the Blitz in London’s Underground, that he saw them less as subterranean than as subhuman. And Lowry?

In 1924, at art school, he painted St Augustine’s, Pendlebury. As befits a student of Valette, the work looks vaguely like Pissarro, its dun-white sky a distant nod to Whistler. If you want to see how old-fashioned it is, make a side trip to the Nevinsons and Gertlers in the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s Crisis of Brilliance. For all that, St Augustine’s is a lovely picture, and artists don’t have to be modern if they don’t want to. Two years later, Lowry painted The Accident, and the rest, as they say, is Lowry.

And where did this new style come from? Primitivism was in the air, even in England: in 1928, Ben Nicholson would “discover” the sailor-painter Alfred Wallis. But Lowry was not so much faux-naive as faux-folk, making work that – in his own imagining, at least – looked as though it might have been made by the people it depicted. That, in itself, is disturbing.

Perhaps he thought he was giving a visual voice to the voiceless. If so, he was wrong. What Lowry did was to dehumanise the urban working class into a mob of flat-capped Morlocks, always on its way to or from but never quite arriving, frozen in a dreadful day of back-to-backs and malnutrition, choking smogs and lice.

Even when a post-war Labour government had eradicated many of these things, Lowry, a Lancashire Tory, continued to see the poor as unevolved, their by now anachronistic sufferings too useful a subject to sacrifice to mere truth-to-life. Its subtle palette apart, I find his work repellent. As to the people who buy it, well ….

To 20 October (tate.org.uk)

CRITIC'S CHOICE

Catch all four of London’s Vermeer paintings in one room at the National Gallery’s new exhibition Vermeer and Music: The Art of Love and Leisure, which considers music as a way of bringing together lovers (to 8 Sept). From sunrise on Friday to sunset on Sunday, Nikhil Chopra’s continuous Coal on Cotton at the Whitworth Gallery, Manchester, looks at the city’s cultural links with Mumbai, in Manchester International Festival (Thurs to 21 July).

NEXT WEEK Charles Darwent high tails it to Mexico at the Royal Academy

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments