Charles Darwent on Uncommon Ground, Land Art in Britain: It may not be big, but it is clever

British land art used to be depressingly small-scale – but this excellent exhibition breaks new ground

I have had one piece of hate-mail as art critic for this paper, in 2003, from a land artist currently in a show called Uncommon Ground at the Southampton City Gallery. "You just don't get it, which is your perogative [sic]," hissed the letter. "You are both, but it is worse to be an amateur than a cynic." Ouch.

It seemed to me, a decade ago, that this pettiness was telling of British land art as a whole. I had just spent a happy fortnight driving across the American south-west, from Walter De Maria's Lightning Field to Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty, via Michael Heizer's Double Negative. You wanted land art? That was land art. The British variant seemed depressingly scaled-down, like a symphony played on spoons. I may have used the word "whimsical" about it. So, I set off to Southampton, hoping to find I'd been wrong.

And, to some extent, I had been, although for the right reasons. British land art is small-minded, in the sense of being about smallness.

As with cowboy films, American land art takes as its starting point an idea of the epic, its aesthetics measured outwards, in increments of vastness. Lightning Field sits on 9,000 acres! James Turrell's Roden Crater is 600 feet high! By comparison, Spiral Jetty's 10-acre site makes it a miniature. This is not a kind of work that is open to artists from a crowded island a third of the size of Texas.

So, the first thing you notice about the land art in Uncommon Ground is that almost none of it involves land. It may involve photographing or filming land, measuring its surface, walking across it or turning it into words: but land itself, no. If American land art is Melville and Longfellow, British is the short story and sonnet. It is necessarily restrictive, and as a result diverse.

So diverse, in fact, that at the start of Uncommon Ground you wonder if "British land art" is a useful term at all. The curators of this clever show have broken their subject down into parts, all dating from between 1966 and 1979. There are surprise inclusions. Antony Gormley a land artist? Well, yes, for a time in the late 1970s. But then pretty well every inclusion is a surprise.

What do Gormley and Garry Fabian Miller and Hamish Fulton and Susan Hiller have in common? During the period in question, they all made work that in some way responded to the land. (A few still do.) I say "in some way" because their responses were so varied and the land so diverse.

The show's curators have listed these variously – by theme as Romantics or Environmentalists, by subject (Parks and Commons, Industrial and Working Landscapes), by material and process (Walking, Filming, Excavation, and so on). But is there a common thread in Uncommon Ground?

There are three. First, to be a land artist in Britain between 1966 and 1979 meant not making the kind of art other people were making: that is mostly to say Op and Pop, shiny art. Even the campest work in this show – Anthony McCall's film, Landscape for Fire, is a contender – has a seriousness that defines itself against the bright colours and shallow surfaces of painting at the time. It is earthy, deep.

And there is something else as well. Gormley's first land art piece had been made in the Arizona desert, although the work was on an insistently man-sized scale – Gormley built and then took apart a cairn, and threw its constituent rocks as far as he could. This was taking a British land art aesthetic into the American lion's den and refusing to be cowed. And yet there was a yearning for what the Americans had, the luxury of possibility.

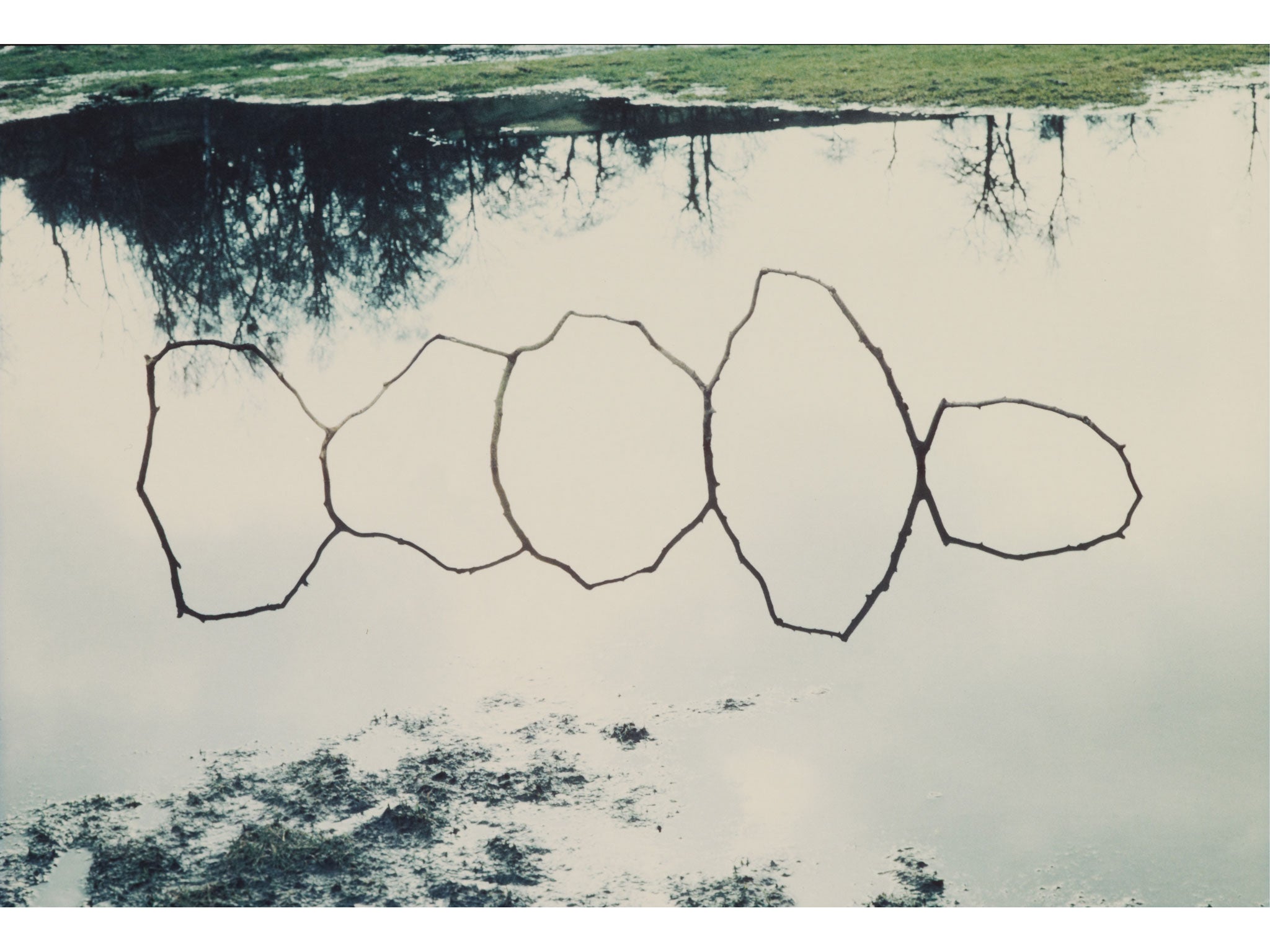

This had not always been a uniquely New World commodity. There lurked, in the British visual memory, a time when not every acre of land was husbanded, when spaces were wide and open. Much of the work in Uncommon Ground tries to recapture that moment: it may have been a post-empire thing. Miller's photo suite, Sections of England: Sea Horizons, re-invokes William Turner, while Andy Goldsworthy's Slate Throw – the artist, tousle-haired, standing on a crag – has a feel of Caspar David Friedrich.

This is not cheap nostalgia. The other thing you notice about much of the work in this excellent show is its air of apocalypse, from the scavenging actors of the Boyle Family's filmed event, Dig, to Derek Jarman's arcadian but worryingly empty A Journey to Avebury. British land art looks backwards with one eyebrow raised, because looking forward seems too scary.

To 3 Aug (02380 832277)

Critic's Choice

Step into the Wellcome Collection in London, and outside your comfort zone. Souzou: Outsider Art from Japan, features 46 artists who are part of social welfare establishments, and proves that the results of art therapy can be fresh and entertaining (to 30 June). Ponder the question of intention at The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things, a touring exhibition which is currently at Nottingham Contemporary (to 30 June).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks