John Berger: Art and Property Now, Inigo Rooms, King's College, London

On the trail of an idol and exotic hero of the old left

In retrospect, there is no doubt that I had a crush on John Berger. He had won the Booker Prize with a phantasmagorical novel called G, then threw the organisers into disarray by announcing that he was giving half the money to the British Black Panthers. In the same year, 1972, he wrote Ways of Seeing, the most arresting television series about art ever made. He was craggily handsome, smoked Gitanes, rode a powerful motorcycle.

And he was both ours – British born and bred – and entirely exotic: he had fled the parochialism of London for the Continent and a mere 10 years later seemed quite unplaceable, pronouncing English slowly and with exaggerated precision, as if handling toxic material with tongs. I was 20 when I interviewed him for a student arts magazine, and I'm sure I wasn't the only undergraduate who wanted nothing better than to be John Berger.

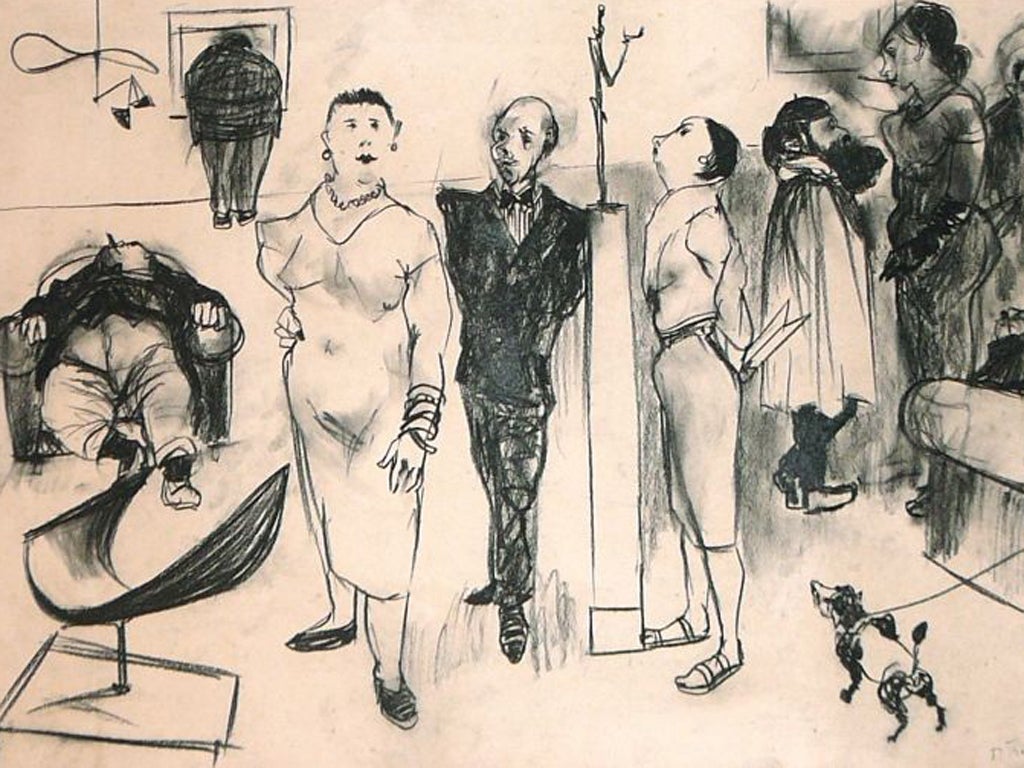

So many of our idols from those years have crumbled: how has this one fared? A sympathetic exhibition in London gives an opportunity to reconsider the work of this gifted artist who gave up painting full-time before he was 30 because, as he wrote, "for me there were too many political urgencies". With press cuttings, photographs, scribbled notes, and a fan letter from Tom Waits, Art and Property Now is a lightning tour through a unique career.

In a series of rooms it charts Berger's development from journeyman painter to critic and novelist then into voluntary exile in France where today he continues to write.

In the 1940s and 1950s, under the influence of intellectual émigrés, Berger became a Marxist art critic for whom society's property relations have a defining effect on the art it produces and values: "being potential slave masters", he wrote, "became part of the Europeans' way of seeing everything". The critic who ignored these factors was complicit in tyranny.

Capitalism and colonialism had not only enslaved half the world but dehumanised the European in the process, making him "clench himself up in his own violence". With the indignation of a revolutionary and the vision of a poet, he forced us to confront this process in G and Ways of Seeing, works that exploded existing categories.

In 1962 Berger left London for good, and very successfully set about turning himself into a European writer. And the more European he became, in his refusal to resort to jokes and his insistence on the political imperatives of writing, the less British.

But in leaving England, did he perhaps lose something vital? Since then he has produced scintillating books but none with the scope or impact of the ones written in his first years of exile. In the long run, the cultural fit with Europe was simply too snug: Berger's seriousness can at times slide into self-parodic solemnity, leading him to make lapidary statements that are not always as profound as they sound.

Speaking about archives – this exhibition selects from the archive he donated to the British Library in 2009 – he told one interviewer, "You enter the past which is as it were in the present tense. And so it's another way of people who lived in the past ... a way of them being present." The English is stilted, the meaning commonplace. Perhaps after all it was the irritation of the London grit that produced the pearls of his career.

To 10 Nov (020-7836 5454)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments