Nigerian Modernism review, Tate Modern – A jubilant panorama of art, from the visceral to the playful

Exhibition brightly illustrates how Nigeria provided the ideal stage for the development of a truly African modern art

Long seen as the poor relation of the international art world, modern African art has undergone a massive surge in prestige and commercial interest over the past two decades. The realisation that contemporary art had to expand its focus beyond Western Europe and North America has seen curators falling over themselves to include artists from this painfully neglected area in major exhibitions and biennales. Tate Modern staged its first retrospective by an African artist, Sudan’s Ibrahim El Salahi, in 2013. But this is the first major exhibition devoted to the development of modernism in a single African country. It focuses, not surprisingly, on the so-called Giant of Africa, the country in which one in four of all Africans live, in the pre- and post-independence era: when Africans were striving for cultural emancipation as well as political and economic liberation.

Nigeria, with its well-developed higher education system – certainly in comparison with its neighbours – plus its array of extraordinarily rich traditions for artists, writers and musicians to draw on, and a vibrant urban popular culture, provided the ideal stage for the development of a truly African modern art.

Exhibitions of non-Western modern art tend to shy away from showing the first gropings towards modernity from artists working in isolation from the international art world, on the grounds that they can be seen as “folksy” and “parochial” – exactly the qualities detractors have tended to highlight in modern African art. This show, however, lets the works of these early explorers shine out. Akinola Lasekan’s paintings of ancient battles and modern-day acrobats may be patently illustrative, but their presence is an honest reflection of what was happening on the ground before the arrival of modernism proper.

Sensitive responses to classical Nigerian sculptures in the much-venerated Ife and Benin traditions, by artists who had in many cases attended London art schools, suggest that the pre-independence era saw a far richer cultural interaction between Britain and Nigeria than we would tend to assume.

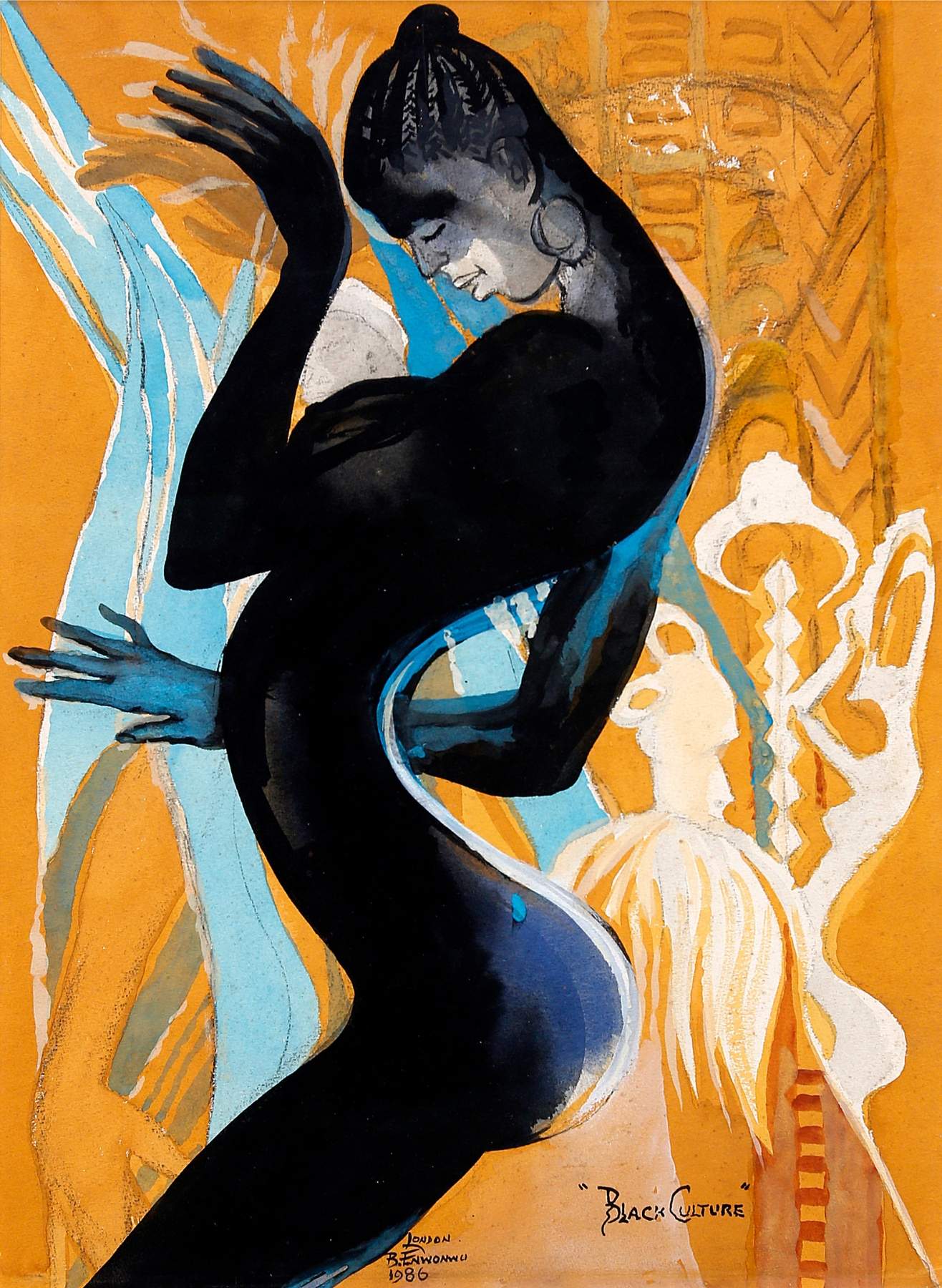

Ben Enwonwu is a titan among such artists, a huge figure in Nigeria. Acclaimed as “the first modern African artist to gain international recognition”, as the wall text has it, he gets an entire large room to himself. If he has never received serious international recognition, it’s perhaps because his attempts to fuse conventional Western representation, Modernist experimentation and traditional African forms appear to fall between stools. Highly accomplished bronze portrait busts bring to mind a slightly African-tinged Jacob Epstein, and Enwonwu was friends with the British Modernist during a long period of living in London. The painted female portrait Tutu (1974) is outright kitsch, while paintings of traditional dances give a slightly uncomfortable sense of the artist looking at his culture through the lens of European modernists who have freely plundered it, but without establishing any sort of critique. More convincing are relatively conventional, but highly atmospheric paintings of the Ogolo masquerade from his own Igbo tradition, which give a rare sense of the meanings of the masked figures and their movements as they’re experienced from the inside.

Most outstanding, however, are life-sized wooden figures of commuters reading newspapers created for the Daily Mirror offices during Enwonwu’s London sojourn, presented as a kind of installation down the centre of the room. While there’s no attempt at realism, the goggle-eyed expressions on the faces are quite hilarious, with the whole timelessly stylised tableau bringing to mind something Epstein himself might have created, if he’d had a sense of humour.

Nigeria’s first avant-garde art movement – the so-called Zaria Rebels, a group of young students at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology in Zaria – staged a classic Modernist revolt against their academically inclined British expat tutors. Their leader Uche Okeke called for a “natural synthesis” of indigenous and imported forms to create “a new culture for a new society… This is our Renaissance era!” But the works by the group’s members struggle to live up to the excitement of that rhetoric. Leading rebel Bruce Onobrakpeya’s mysterious anthropomorphic images of forests are stronger than his overtly Christian lino cuts. Yusuf Grillo’s images of women and warriors, from the early Sixties, tend towards an expressionistic, self-consciously “primitive” sensibility that was very prevalent among Western illustrators at the time. His friend Jimoh Akolo’s Fulani Horsemen is in a similarly decorative groove, which, judging by its prominent use in the show’s publicity, is likely to prove more popular with Tate visitors than a room full of austere Western-inspired abstraction ever could.

Akolo’s more visceral, but similarly brilliantly coloured Man Hanging from a Tree (1963) compels because it shrugs off the compulsion to illustrate Nigerian culture that seems to come with these artists’ awareness of their role in “nation building”. The contrast between Clara Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu’s elegant Abstract (1960) and her Elemu Yoruba Palm Wine Seller (1963) suggests this pioneering woman artist gave up a promising career as an abstract painter in favour of clunky figurative folklore.

If this national focus runs counter to the international, even universalist aspirations of Modernism as we tend to understand it, Nigeria had its own utopian High Modernist moment in the Mbari Club. This meeting place for artists and writers in the university city of Ibadan remains iconic in Nigeria as an embodiment of pan-diasporic, multi-disciplinary experimentation. Legendary bandleader Fela Kuti debuted there, while key plays by Wole Soyinka, Africa’s first Nobel prize winner, were premiered. The club’s German-born convener Ulli Beier raised funding for visits by major Black artists from across Africa, America and the Caribbean. While the show assembles a nice selection of works from visiting artists including Ibrahim El-Salahi, Ethiopia’s Skunder Boghossian and the Japanese printmaker Naoko Matsubara, the cross-disciplinary aspect, which is as intrinsic to traditional African culture as it is to Modernism, feels a shade under-explored.

Beier, a junior lecturer at Ibadan’s university, also had a hand in the so-called Oshogbo School. These workshops offered free-form art classes to unemployed youths, whose exuberant prints and paintings became controversial when they attracted more international acclaim than the work of many of the country’s professionally trained artists. The paintings of Muraina Oyelami and the lino cuts of Jacob Afolabi, to name just two alumni, have a fiercely uninhibited expressionistic quality that Western artists of the order of Paul Klee and Jean Dubuffet would have envied.

This show offers a jubilant panorama of the birth of modern art in an embattled emergent nation. If the horrors of the Biafran War of 1967 to 1970 seemed to bring Nigeria’s Modernist moment to a standstill, the artists struggled on through a string of mostly corrupt military governments and the highs and lows of the country’s petrochemical boom to see contemporary artists such as El Anatsui and Ndidi Dike, both featured in the show’s final room, acclaimed as modern masters.

There’s plenty of work in this exhibition that doesn’t fall in line with tasteful Western expectations of what international Modernism ought to be like. But that’s because the art and the artists who created it were genuinely embedded in the cultural interactions that surrounded them, rather than floating in a generalised, global art-world ether, as most art, no matter where it’s produced, does today. Their energy, humour and ambition won’t fail to leave you on a high.

Nigerian Modernism is at Tate Modern from 8 Oct until 10 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments-Tate--Succession-Picasso-DACS-London-2025.jpg?quality=75&width=230&crop=3%3A2%2Csmart&auto=webp)

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks