Painting the Modern Garden: Monet to Matisse, Royal Academy, review: A vibrant tonic for a bleak midwinter

The Royal Academy’s new exhibition showcases the ‘garden’ works of Monet, Renoir and Pissarro

The cynical critic should be pardoned for questioning whether it was really necessary to have yet another show with Monet in the title, but entering the spacious galleries I am quickly disarmed by the pops of colour lighting up the gloom of winter.

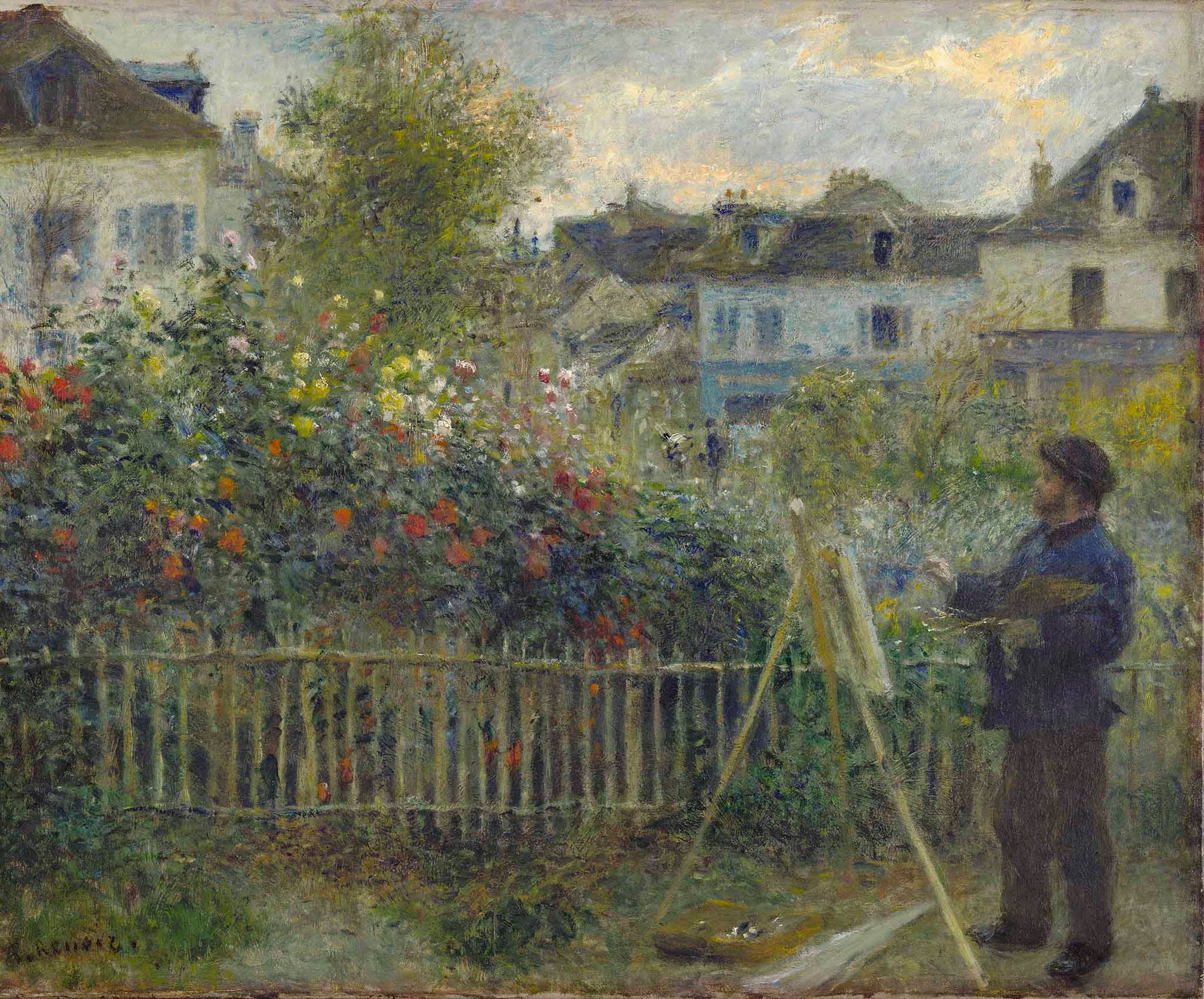

The scene is set here with three paintings ranged next to each other. A painting by Monet, The Artist’s Garden in Argenteuil (a Corner of the Garden with Dahlias), from 1873, is juxtaposed to Renoir’s Monet Painting in his Garden at Argenteuil of the same year. Renoir’s work provides a valuable insight into the working practice of Monet, the artist, is depicted painting en plein air, palette in one arm, canvas on easel, perhaps the very work that is now adjacent to this one. The difference between the end results of Monet and Renoir is laid out for the viewer with the directness and pleasure of Monet’s entire dream-like scene juxtaposed to the slightly more workmanlike depiction of Renoir, delectable though it is. The third painting on this wall is Kitchen Gardens at L’Hermitage, Pontoise by Camille Pissarro (1874). It illustrates Pissarro’s professed preference for vegetable gardens. Contemporary critics lambasted the artist for being an “Impressionist market gardener specialising in cabbages”. Whatever you think of these very wonderful brassicas, this wall sets the scene for a series of works by a plethora of artists using flowers and gardens as their excuse for producing canvases of pure experiential pleasure.

Further along is one of the strangest paintings in the exhibition, Monet’s The Artist’s Garden at Vétheuil (1881), which shows the artist’s two sons on the steps of their house. Monet’s recent sojourn in Holland is commemorated in the delft pots standing sentinel by the staircase; the two young lads are dwarfed by monstrous sunflowers, all capped by a threatening sky. It is a painting from a private California collection that I have never seen before, and shows an artist able to depict without being photographic.

Family Reunion on the Terrace at Meric (1867), by the less well-known artist Frédéric Bazille, illustrates a sun-drenched garden and a bench placed in the welcome shade, on which is seated an unfinished partially sketched woman. It was painted shortly before the artist was tragically killed in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, his career cut short with few works remaining. The pricks of colour remind us of the tragedy of his and many others’ lives lost in the events of this period.

There are many other works to bring pleasure to the viewer. A single painting, Woman and Child in a Meadow at Bougival (1882), by Berthe Morisot, one of just the two women in the show, shows one of the artist’s favourite subjects, a mother and child; the mother admiring the flower that her young daughter had brought for her inspection. The entire scene is painted in a semi-vortex of painterly freedom. This is very daring painting for its time, something that we need to keep reminding ourselves of as we process through the exhibition. These very artists have made us comfortable with the transformation of documentation into something different, an expression of a moment, an “impression” of life. Indeed, even the term impressionism was coined as a negative phrase by the then contemporary critic Louis Leroy, who declared that Monet’s painting was, at most, a sketch, and could hardly be termed a finished work.

Nearby is Édouard Manet’s Young Woman Among Flowers (1879), where we painlessly accept the portrayal of an almost featureless woman standing among a morass of flowers that are impossible to classify: a smear of yellow, a smudge of carmine: all that is necessary to alert the viewer as to the content of the scene.

Claude Monet acquired his house and gardens in Giverny in 1883, where he lived until his death in 1926. Now a popular destination for art and garden lovers, it proved to be where he could finally channel his profound love of plants and horticulture into a suitable property. At the beginning it was undeniably a financial strain, necessitating letters to his dealers asking for money – “lots of it” – so he could acquire the property. As prosperity followed, his love affair with nature continued until his death. His ambitions began to grow both in horticulture and artistically as he employed more gardeners. As the canvases became bigger, Monet was to abandon outdoor painting and create a studio in which he could work no matter what the weather. He started the large project of paintings of water lilies that he hoped to house in a building accessible to the French nation.

Ann Dumas, the curator of this leg of the exhibition, chose as her exhibition designer Paris-based Robert Carsen, who works largely on opera design. She tells me that she wanted him in order “to inject a bit of fun” into the show. This explains his build-out of conservatory-like structures in the central octagon space, complete with fake plants, which also contains the documentation for Monet’s life in Giverny. What Carsen also brings to the party is a total respect of the paintings’ ability to stand alone, choosing to bank much of the documentation in this single room.

Carsen chose to use argil paints that are made with natural materials; clay, marble and chalk, which he has never seen in England. The colours absorb the light and in the “punnily” named Avant Gardens Gallery, three of these colours are used to great effect in this room of delicious treats. The juxtaposition of two different blues and green walls should not work together, but they do. Henri Matisse’s Palm Leaf, Tangier (1912) is one of the most abstracted works in the exhibition, which Matisse himself described as a “burst of spontaneous creation like a flame”. The confidence to allow a central patch of almost blank canvas, scratched marks, and a few marks has produced wonderful results.

There is a bank of pure colour in a group of portraits of blooms by the phenomenal painter Emil Nolde, who said “the flowers would greet me jubilantly with their pure and beautiful colours”. There are singular works by Wassily Kandinsky, Gabriele Münter (the second woman in the show, who was living with Kandinsky at the time she painted the work), August Macke and Paul Klee all riffing off the subject of gardens, each in their inimitable style.

Sometimes it is easy to forget to contextualise when and where works are being made, and it is important to remember that many of these works were painted during the First World War. Is it self-indulgent to be painting flowers when there is so much death so near by? Matisse attempted to volunteer to fight, but was refused due to age and health issues. Monet said in December of 1914: “I resumed work… it’s the best way to avoid thinking of these sad times. All the same I feel ashamed to think about my little researches into form and colour, while so many people are suffering and dying for us.” In 1918 Matisse said: “I paint to forget about everything else.”

There are some missteps in this exhibition, most notably a room of paintings by the Spaniard artist Santiago Rusiñol that add little to the argument. I am not convinced by Joaquín Sorolla, another Spaniard who seems oddly out of place. I would prune out the weaker American impressionists, including Childe Hassam, and there are better works by John Singer Sargents than the horrid Garden Study of the Vicker’s Children. It would have been wise to also have weeded out some of the second-tier French artists such as Henri Le Sidaner. But these are quibbles in a show filled with pleasurable works not only by Monet but Pissarro, Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard too.

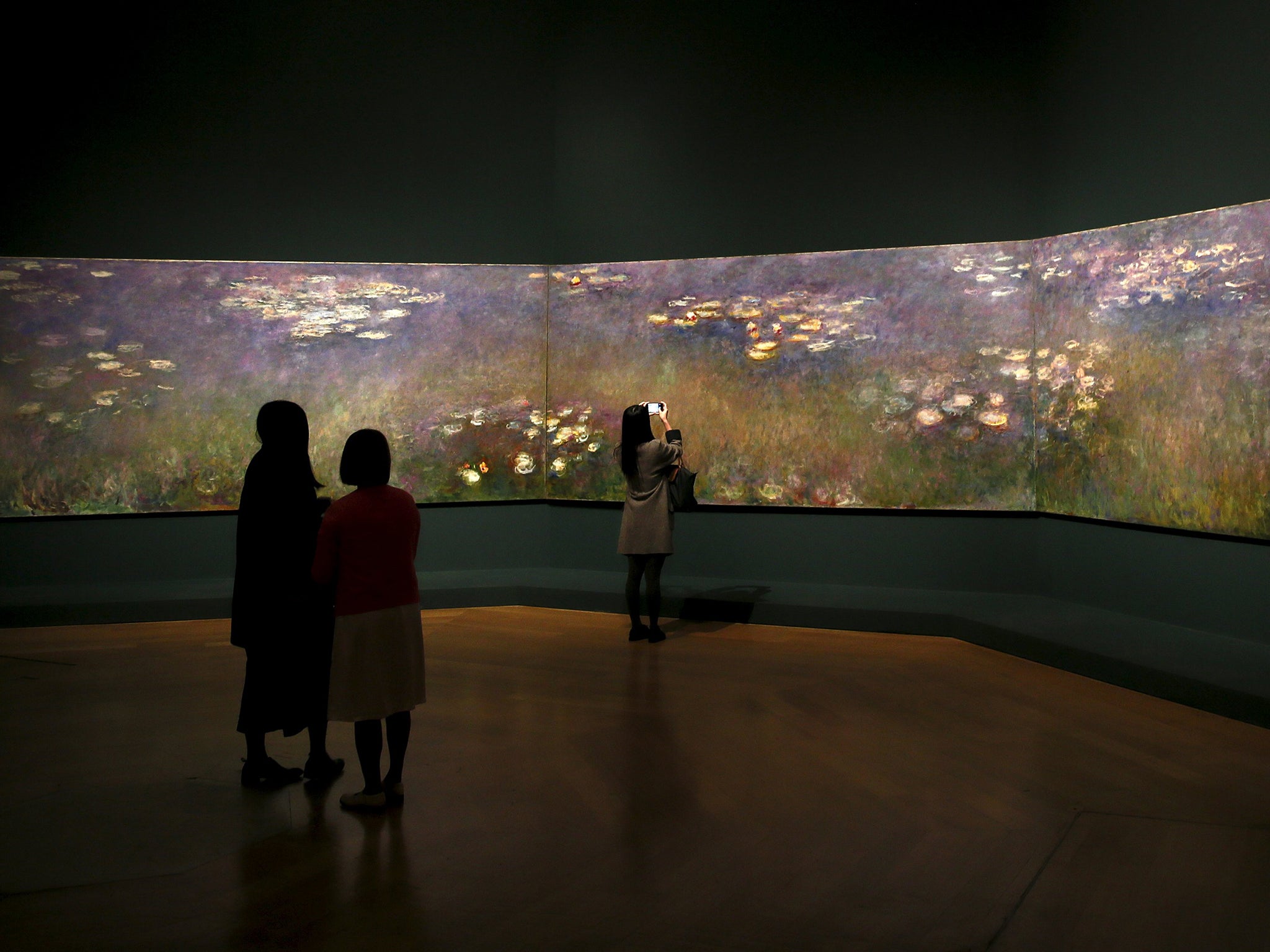

I left the exhibition through two wonderful rooms of Monet, a group that includes paintings from Giverny, and most touching Water Lilies with Weeping Willows (1916–1919), a work that seems to encapsulate Monet’s sadness at the time. The aptly named weeping willows bend over his beloved lily pond, symbolising perhaps the nation’s grief for fallen soldiers. The last room includes three water-lily panels brought together for the first time in Europe, juxtaposed to form a curving continuous frieze. What a journey we follow of an artist who started in pure depiction in Spring Flowers (1864) ending in this room of distilled pure experience. What an inspiration Monet’s oeuvre has been and continues to exert. What a beauteous place to stand in the bleak midwinter.

‘Painting the Modern Garden: Monet to Matisse’, Royal Academy, London W1 to 20 April (020 7300 8090)

Buy tickets for Painting the Modern Garden: Monet to Matisse with Independent Tickets

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments