Palladio, Royal Academy of Arts, London

Any visitor to London's Royal Academy of Arts comes charged with expectations that he or she will see a show that combines intellectual merit with visual panache. There have been many past triumphs, from the great show devoted to the arts of Africa, to the more recent survey of Western portraiture in collaboration with the Grand Palais in Paris.

Regrettably, this story of the life and work of the great Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio (1508-1580), whose villas, churches and other buildings we can see in Venice, Vicenza and the Veneto region, is a disappointment by comparison. In fact, it is a bit of a sad mess.

Things don't augur well from the outset. Stand outside in the RA courtyard, and you will see, to the left and right of the entrance, two not very large, limp banners announcing the show's opening, greatly outshone by the announcement for the Byzantium exhibition, which opened last year. Why so small? Why so limp? It can't be today's unremitting drizzle alone.

Now, it has to be said that any exhibition that tries to present the story of the triumphs of an architect is up against it from the start. Why? Because, unlike paintings and sculptures, buildings cannot be readily transported from Vicenza to London. So you are left with all the, albeit fascinating, ancillary stuff. Who he knew and worked with – which means portraits of his famous contemporaries, usually interesting from a documentary point of view, but not necessarily great works in their own right. Even the portrait of Palladio himself looks far better in reproduction than in this gallery.

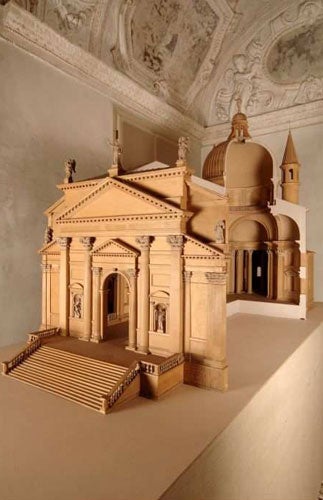

What else? Well, there are the things that prove he was generally hard at work – account books; bits of hewn stone; tools of the trade. There are also, lining almost every wall, scores of his own architectural drawings, some of elevations, some of façades, some of details of the antique buildings he was seeing and, as he drew them, analysing. And then there are the architectural models, of churches and villas, for example. Some of them yawn open, like boxes, so you can see their interiors. There are many of these. In fact, there are too many, and in the second of the exhibition's four galleries, the jamming together of architectural models makes it feel a bit like a lumber room.

They also turn up again when you thought you had done with them, and had moved on to some other part of the show. It's a bit like Piccadilly Circus in about 1911 or so, when they were just changing over from horse-drawn to motorised omnibuses. Architectural models are marvellous things, but they do feel relentlessly low-tech these days. We know we can't transport buildings by pantechnicon. But could not someone have at least produced a virtual tour of one of those great buildings, to help us feel our way around at least one of those extraordinary interiors?

The greatest failure of all, however, is a failure of design. There is no natural sweep and flow to this show – with the exception of the first gallery, which feels like an impressive beginning. After that, the show flounders around, visually and thematically. The second gallery feels too full, the third too empty. Many of the drawings are mounted on to panels of grey wood that seem to lean against the walls, so that we see the original decor in messy combination with bits of temporary installation. In the third gallery we have pretty, Palladio-esque(ish) stencilling effects on the walls as visual background music. So why didn't we have something similar in the second gallery, rather than the bald clash of grey painted wood against the original red? Many of the wall captions are too stingily small, and they are often printed white against grey, which makes them almost illegible. Good job they were too small to read in the first place!

In short, the entire overambitious enterprise feels badly underfunded, poorly thought through, and fairly sloppily executed. Palladio, that scrupulous genius, wouldn't haven't raised his hat to this tribute.

To 13 April (0870 848 8484)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks