Van Gogh and Japan, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, review: It delves into this subject as never before

The exhibition highlights the influence of Japanese art on Van Gogh with 60 of his paintings and drawings – and a collection of Japanese woodblock prints by Hiroshige, Hokusai and Kuniyoshi

When that passionate painter Vincent van Gogh came to live in Paris in 1886, he was a man in pursuit of a new vision of modernity. And where better to find it than in the art of Japan? Japan had opened up to the West in 1864, and from that moment on Paris became agog with all things Japanese. Van Gogh began to buy large quantities of Japanese woodblock prints. He even hoped to trade in them. Unsuccessfully, as it happens. His vast store – he came to own about 600 of them – were pinned up on his studio walls, and often treated with very little respect indeed. He carried them around with him. He stuck pins into them. After all, they were teaching tools. What appealed to him about the Japanese aesthetic? And what exactly did he learn?

This show at the Van Gogh Museum, which gathers together 60 paintings and drawings by Van Gogh himself and a considerable collection of Japanese woodblock prints by the likes of Hiroshige, Hokusai and Kuniyoshi, has been five years in the making, and it delves into this subject as never before.

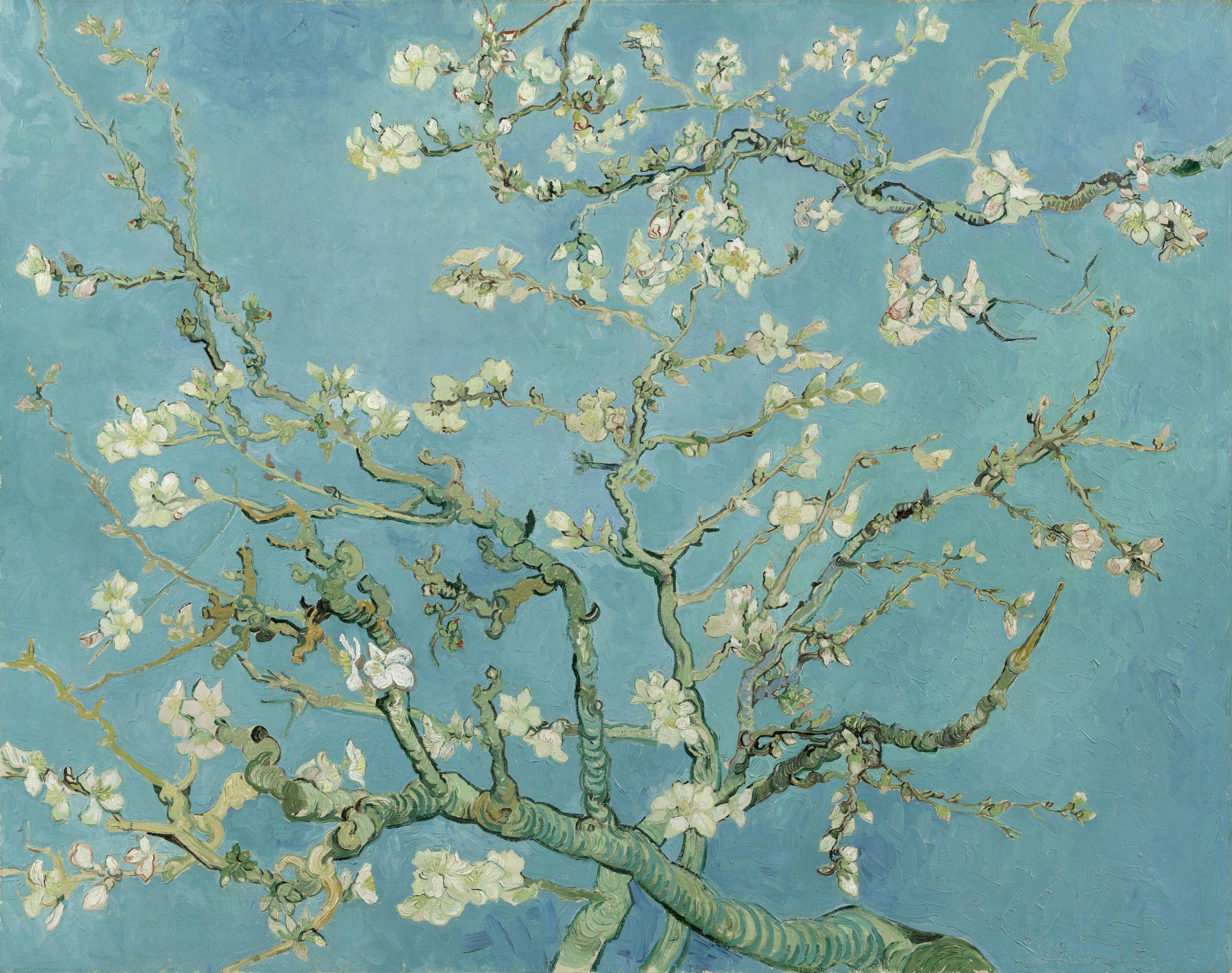

It shows us, at first, Van Gogh the copyist, and then, a little later on – Van Gogh’s art always developed at great speed – Van Gogh as the great beneficiary of Japanese influence. Van Gogh saw two things: a way of making which might prove to be a model for a community of like-minded French artists. After all, did not the Japanese work harmoniously together – rather like monks? And then – of equal importance – how exactly the Japanese had produced their pictorial effects. He studied them assiduously. He learnt from their use of bold and contrasting colour. He studied their compositional clarity, their fluidity of line, their unusual croppings of natural forms. He admired their beautiful women in silk kimonos, so at one with the natural world in which they lingered and languished, the furious attention they paid to the smallest of details. These works made him happy, he wrote.

By 1888, he had moved to Arles in pursuit of a countryside which would speak to him of his idealised vision of Japan, in which he too might become a monkish figure, wholly devoted to an art which would be flooded with a light which would both warm him and cheer him. He produced many great works in a very short period of time. The local postman’s wife is nipponified – as is the wife of the owner of the cafe. Alas, he had not reckoned on the single greatest obstacle to his vision of an elevated worldly of fraternal art-making: his companion, Paul Gauguin.

Their relationship in the Yellow House, far too small for two impassioned and rivalrous men, became horribly fractious. Seized by a psychotic moment, Van Gogh lopped off his own ear, and that famous painting of the earless painter, bandaging a yawning absence, has been borrowed from the Courtauld Gallery in London. It demonstrates the end of a dream – and yet the dream still lingers in the image of the Japanese print at his back. Van Gogh would never rid himself entirely of Japonisme. It had done him much good – for all the hopeless dreaming about the spirit of community.

Until 24 June (vangoghmuseum.nl)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks