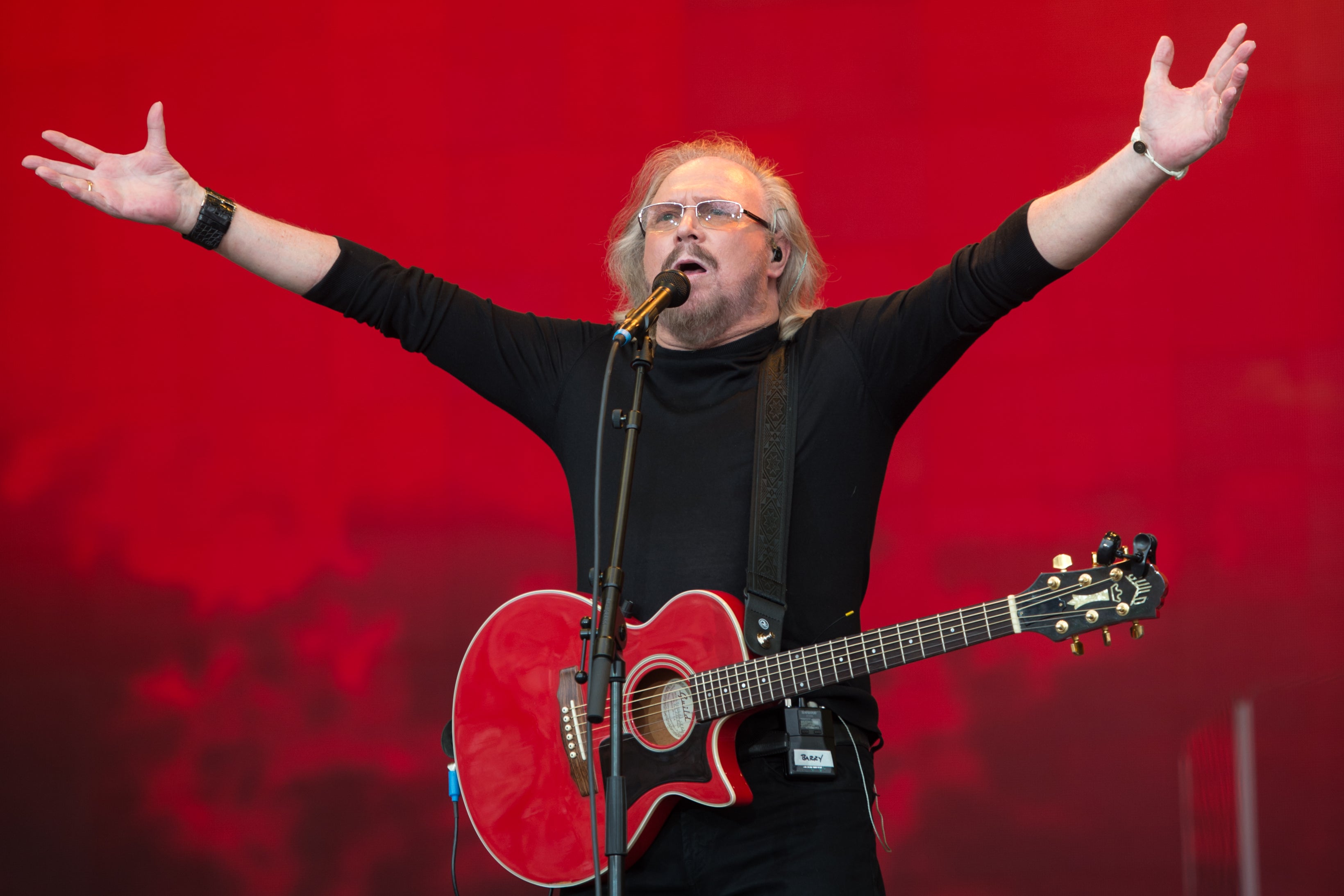

‘The mission is to keep the music alive no matter what’

As the last member of the Bee Gees, Barry Gibb is making sure their sound lives on. Alex Pappademas speaks to the legendary artist about disco, ‘Grease’ and his latest album

Earth’s last surviving Bee Gee is calling from his home studio in South Florida, just steps from the waters of Biscayne Bay.

“I used to have a great boat,” Barry Gibb says. “A speedboat.” He calls it Spirits Having Flown, after a 1979 Bee Gees album that has sold more than 25 million copies worldwide. “I would tear around the bay and get ideas.”

Sometimes he doesn’t even need the boat. One day the Bee Gees’ manager, Robert Stigwood, called. He was producing the film version of the musical Grease and needed a new title song. Gibb had not seen the film; this was a creative challenge.

“How in heaven’s name,” he asks himself, “do you write a song called Grease? I remember walking around on the dock, and it suddenly occurred to me that it’s a word, and you’ve just got to write about the word.”

“Grease is the word,” he wrote, “is the word that you heard. It’s got a groove, it’s got a meaning.”

He solved his problem and had seen the light; the word was “grease”, and the word was good. Grease, recorded by Frankie Valli, was released in May 1978 and reached No 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart by the end of August.

It was Gibb’s seventh writing credit on a No 1 hit that year, after How Deep Is Your Love, Stayin’ Alive, Night Fever and If I Can’t Have You, all from the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack, and Shadow Dancing and (Love Is) Thicker Than Water, solo singles Barry helped write for his brother Andy Gibb. On the Hot 100 for the week of 3 March 1978, songs by the Brothers Gibb made up three of the week’s Top 5.

It was like this for a long while – No 1 hits, one after another after another – and then it wasn’t.

In the early 1970s, the Bee Gees came to Miami to try making records in America. This worked out rather well for them, and Barry has lived there ever since.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

“It’s just a big old house. I would never classify it as a mansion,” says Gibb, who in the time he’s lived here has counted Matt Damon, Dwyane Wade and Pablo Escobar among his neighbours.

He is 74, and his legendary lion’s-mane hair is grey and wispy under an Australian-style leather bush hat. His words slip past his still-magnificent teeth in a rich, almost Connery-esque brogue that his origins (born on the Isle of Man, raised in Manchester and then Australia) don’t fully explain.

Gibb’s latest album, Greenfields: The Gibb Brothers Songbook, Vol 1, goes on sale in January; it’s preceded this month by director Frank Marshall’s HBO documentary The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart. Early in the film, we see Gibb and his brothers Maurice and Robin the way most people remember them – in open-necked shirts of shimmering silver, medallions blinging brightly against their mammalian chests.

Then a spotlight homes in on him, cropping out the rest of the band. This is foreshadowing by literal shadow. Since 1979, Gibb has lost three brothers. Andy – the youngest, who soared as a solo artist under Barry’s tutelage but struggled with drug addiction – died first in 1988, at 30, of myocarditis. Maurice died in 2003, of complications caused by a twisted intestine; Robin died in 2012, of complications of cancer and intestinal surgery.

Gibb has only a passing acquaintance with modern pop music, which he understands to be a world ruled by children who go by nicknames and numbers

This leaves Barry as the living steward of a catalogue of songs that have become contemporary standards, performed and recorded by Janis Joplin (who sang To Love Somebody at Woodstock) and Destiny’s Child (who covered Emotion on their third album), as well as the Rev Al Green, irreverent Texas punkers the Dicks, Bruce Springsteen and Miss Piggy. A world in which no one sings Bee Gees songs anymore is hard to imagine for karaoke-related reasons alone, but Gibb has seen enough to understand that nothing is forever.

“The mission,” he says, “is to keep the music alive. Regardless of us, regardless of me. One day, like my brothers, I will no longer be around, and I want the music to last. So I’m going to play it no matter what.”

Falling hard for bluegrass

Gibb has only a passing acquaintance with modern pop music, which he understands to be a world ruled by children who go by nicknames and numbers. He hopes that someone is giving them good advice.

“He doesn’t listen to a lot of new music,” says his son Stephen Gibb. “He listens to the music of his youth.”

Gibb’s earliest memories of music are of harmony – the Everly Brothers and the Ohioan jazz vocal quartet the Mills Brothers, playing from a single speaker in his parents’ house. He can draw a direct line from that to everything else; it’s why he, Robin and Maurice started singing together.

But after that, what got into Gibb’s head was country music, particularly once the Gibbs moved from England to Australia in 1958, just before Barry’s 12th birthday.

“Bluegrass music,” Gibb says. “I fell in love with that. I became obsessed with that when I was a kid, because you didn’t hear much else but bluegrass music in 1958 in Australia.”

While exiled from the charts in the 80s, Gibb and his brothers wrote country hits for Conway Twitty, Olivia Newton-John and – most famously – Islands in the Stream, a worldwide smash for Kenny Rogers and Dolly Parton.

“Kenny always says, ‘I still don’t understand that song. I’m not sure what it’s about,’” Gibb says. “I say, ‘Kenny, I understand that song – it’s a No 1 record.’”

Gibb explains there’s always been country in the Bee Gees’ sound, whether or not his brothers particularly wanted it there. But the idea of doing a full-length country album had been a bucket-list item for decades, until last year, when the Bee Gees signed a new deal with Capitol Records. There were discussions about Gibb revisiting the catalogue in some way; Gibb realised his country moment had arrived.

“I had been turning my dad on to Jason Isbell and Chris Stapleton and Brandi Carlile and Sturgill Simpson,” Stephen Gibb says. “He’s like, ‘Jesus, these records are great. These are brilliant’. The common thread on a lot of those records turned out to be Dave Cobb.”

Cobb has won Grammys for his work with Carlile, Stapleton and Isbell; he also turned out to be a massive Bee Gees fan. By October 2019, Gibb was at RCA’s Studio A in Nashville, recording new versions of Bee Gees classics and obscurities with a range of country-associated duet partners: modern hitmakers like Keith Urban, traditionalists like Alison Krauss, Gillian Welch and David Rawlings, icons like Parton.

Parton and Gibb cut their rendition of the Bee Gees’ plaintive 1968 single Words on the first day of recording. Cobb describes it as “probably the most intimidating session I’ve ever had in my life”. He remembers walking out to the microphone to play guitar, “and my legs started trembling a little bit”.

Isbell was equally intimidated about singing with Gibb on Words of a Fool, a deep cut Gibb wrote for the soundtrack of the long-forgotten 1988 film Hawks.

“At one point I was trying to sing a harmony part over Barry,” Isbell says, “and Dave said something, and I said, ‘Dave, one of us is not Barry Gibb, man – you have to back off a little bit and give me a few more tries at this.’”

We’d suddenly tumbled into flower power. The whole idea was to find out what character you’d dress yourself up as

Gibb’s voice on Words of a Fool is strong but also spectral, its shuddering vibrato bringing to mind jazz singer Jimmy Scott. Nearly six decades after he first sang on a record, it remains one of the most otherworldly instruments in popular music.

“I asked him how the hell he still sounds like that,” Isbell says. “I’m always afraid to ask people that question, because I don’t want to offend them by acknowledging their age, but I said, ‘Barry, how can you still sing so beautifully and powerfully?’ And he said, ‘I never really liked cocaine. You had to do it every 15 minutes for it to work. So it just didn’t appeal to me.’ That’s the perfect answer to that question.”

A quavering sadness

It’s not surprising that Gibb found his way to country music. Listen to To Love Somebody, on which he builds from a gruff, tight delivery before releasing exquisite high notes, as if a dam is finally breaking inside him. It’s a voice made for country singing, because it’s a voice made for sad songs.

Gibb has written a lot of those. In 1964 alone, his copyrights as a songwriter included songs called Scared of Losing You, Claustrophobia, I Just Don’t Like to be Alone, House Without Windows, Now Comes the Pain, Since I Lost You, and This Is the End.

In Australia, despite being underage, the brothers played in bars, Gibb says, that were “Crocodile Dundee all the way”. He says the Australian audiences were amazing, “but it’s a drinking audience. We witnessed a lot of fights while we were singing. I saw two guys punch each other out without standing up”.

The minute they had a hit, with a song called Spicks and Specks – “Robin used to say that was our first No 1, but it was really only No 1 in Perth” – they set sail back to England, signed with Stigwood, then an associate of Beatles impresario Brian Epstein, and encountered 60s London in full swing.

“We’d suddenly tumbled into flower power,” Gibb says. “The whole idea was to find out what character you’d dress yourself up as.” He describes a vivid memory of getting in an elevator with Eric Clapton. “He’s dressed as a cowboy and I’m dressed as a priest.”

Gibb was 20 then; his brothers were not yet 18. “We were still kids,” he says, “and we were still very naive. I don’t think the naivete went away for a long time.”

They did soon discover booze, pot and pills, Gibb says. But early British albums like Bee Gees’ 1st from 1967 – with its trippy Klaus Voormann cover, oddball orchestration, and titles like Every Christian Lion Hearted Man Will Show You – made them seem like more active participants in the 60s lifestyle than they were. Barry and Robin Gibb were once given a mescaline tablet; they decided to flush it down the toilet.

As steeped as they are in the vibes of the moment, the late-60s Bee Gees albums are also shot through with a twee, quavering sadness that feels unique to the Gibbs. They sound like the work of infirm boy-princes who’ve mastered the pop landscape by staring down longingly at it from the window of a tall tower. Drugs alone could not yield music this unaccountably odd.

“You have no idea how humans got in a room and made those records,” says Cobb, who found his way to the band’s 60s material via an obsession with the Beatles and the Zombies’ Odessey and Oracle. “They just are. They feel like they’re coming from an alternate universe.”

But even their alternate-universe albums were aimed at the charts. They never had a Brian Wilson lost-in-the-sandbox experimental phase. They were true immigrant hustlers, adaptable and industrious. They worked for Stigwood, who both managed them and owned their recordings, a conflict of interest that went unexamined for decades.

By 1969 all three Bee Gees were married and living separate lives.

“I think we stopped really knowing each other after we arrived in England,” Gibb says. They began to argue the way only a band of brothers with two frontmen – Barry and Robin – could. Robin Gibb left the band in 1969, returning after 18 months at Stigwood’s urging. Many issues, Gibb says, remained unresolved. Instead of talking, they wrote How Can You Mend a Broken Heart together, singing to each other the things they couldn’t say.

Their early 70s work represented a low creative ebb; after they relocated to Miami at the suggestion of their friend Clapton, they began making some of the biggest records of all time.

Songs like the sublime Jive Talkin’ had a heavier beat than anything they’d done before. Gibb thought of their new direction as a move towards R&B. But their contribution to Saturday Night Fever, a 1977 blockbuster produced by Stigwood, would redefine them differently. The minute John Travolta strutted down a Bay Ridge boulevard in New York to the supple bass line of Stayin’ Alive – a showcase for the anguished falsetto Barry Gibb had lately discovered – they became a disco act.

“We got sucked into that,” Gibb says. “We were just making records we loved. In fact, we didn’t even call them ‘disco’. I never thought a Stylistics record was disco, and I never thought Shining Star by the Manhattans was a disco record, and Too Much Heaven was not a disco record. How Deep Is Your Love is not a disco record. But you get classified.”

Everything that they had ever dreamed of was happening. They were at the pinnacle. And suddenly it became a nightmare

The film’s soundtrack album became their biggest hit; it has been certified platinum 16 times and remains the second-biggest soundtrack album of all time, after Whitney Houston’s The Bodyguard.

Caught in the 'Disco Sucks' crosshairs

In 1979, as the Bee Gees toured the world in a customized Boeing 720 passenger jet with their logo painted on the tail, a reactionary anti-disco movement was coalescing among white rock ’n’ roll fans. Between games at a White Sox doubleheader that summer, a Chicago DJ named Steve Dahl blew up a crate full of disco records on the field at Comiskey Park.

In Marshall’s film, Chicago house-music producer Vince Lawrence – who was working as a Comiskey Park usher that night – recalls seeing people showing up that day carrying records by Black artists who had nothing to do with disco, and describes the event as a “racist, homophobic book-burning”.

Disco, as a cultural phenomenon, was Black, brown and gay; the fact that the Bee Gees were none of these things didn’t stop them from being caught in the crossfire. They were the genre’s pop avatars, and the “Disco Sucks” movement would turn them into instant pariahs. Marshall’s film cuts back and forth between the countdown to the explosion and shots of the band onstage, smiling in silver, looking utterly unaware of the destiny bearing down on them like a train.

“The dynamic of their situation changed overnight,” Marshall says. “Everything that they had ever dreamed of was happening. They were at the pinnacle. And suddenly it became a nightmare, and they had to have escorts and there were bomb threats. And they’d go ‘Wait, we’re just a band’ – but it was much bigger than them. It was history, and they were caught in the middle. Their biggest moment became their biggest nightmare. I really loved that irony.”

Gibb says he never let the Comiskey event bother him: “I knew that whatever it is you do has to come to an end, no matter what it is.”

But of course the end is never the end, when you’re a Bee Gee. After the bell tolled for disco, Gibb and his brothers were a punchline and a punching bag for a long while. Gibb admits he was “a little upset” the first time he saw the Barry Gibb Talk Show sketch on Saturday Night Live, in which Jimmy Fallon played Gibb as a rageful, dyspeptic peacock while Justin Timberlake, as Robin Gibb, struggled to keep a straight face – but mostly because, in real life, “Robin was the one who was always angry”. (He popped up on a 2013 Christmas episode of SNL to sing with Fallon and Timberlake. No hard feelings.)

Gibb doesn’t expect to conquer the pop charts again; making more records like this duets one would be enough.

“I’m a country singer,” he says. “I’ll always be a country singer. I’ve managed to shed all of these other things. I don’t even have a white suit anymore.”

But he’s lived long enough to see the conversation change around his music. There are dozens of videos online in which YouTubers – mostly Black, mostly too young to even remember Wyclef Jean sampling Stayin’ Alive in the late 90s – react to the Bee Gees’ video for the Spirits Having Flown ballad Too Much Heaven.

The video is a quintessential document of its era, like a loose quaalude fished from the couch cushions of time. The Bee Gees are singing in a fern-filled recording studio, backed by a string section. They’re wearing open-necked silk shirts. Gibb’s jeans are a lewd joke about avocados. So at first, the YouTubers are sceptical. Then, pretty much without exception, they’re struck speechless when the vocals come in and Gibb and his brothers begin building a cathedral with nothing but the breath in their lungs.

Gibb has not seen these videos. But he has watched a few clips of young people covering Bee Gees songs like How Deep Is Your Love online, and some of them aren’t half bad. “This one boy couldn’t have been more than 11 or 12 years old. Whoever he is, he will be one of the greats if he keeps his head. That’s always the question. Right? Always the question.”

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks